yogabook / functional exercises / deadlift

Contents

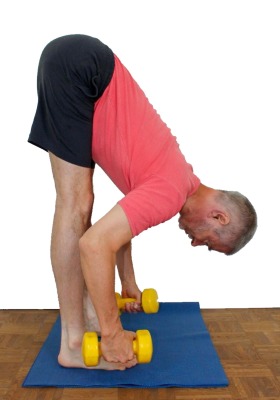

„deadlift“

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

Tue und lasse

At no time ..  | .. make your back bend | Always stretch your back |

Detailfotos

Maintain the physiological lordosis of the lumbar spine up to the final position | Starting position: 20° in front of vertical is sufficient | keep your back straight at all angles, which is particularly difficult with wide flexion in the hip joints and requires a lot of effort from the back muscles |

Feedback: We look forward to hearing what you think about this description, please give us feedback at

postmeister@yogabook.org

last update: 30.12.2018

Trivia name: Deadlift

Level: A

- Classification: A

- Contraindication

- Effects of

- Preparation

- follow-up

- derived asanas

- similar asanas

- diagnostics

- Instruction

- details

- Variants

Classification

classic: functional exercise

physiological: strengthens mainly the hamstrings, further the triceps surae and the autochthonous back muscles

Contraindication

Effects

- (552) Strengthening the quadratus lumborum

- (852) Strengthening the calves

- (722) Strengthening the hamstrings

- (602) Strengthening the back extensors

- (632) Strengthening the muscles of the thoracic spine

- (642) Strengthening the muscles of the lumbar spine

- (822) Strengthening the hamstrings as external rotators of the knee joint

- (721) Stretching the hamstrings

Preparation

Follow-up

Derived asanas:

Similar asanas:

Diagnostics (No.)

Variants:

Instructions

- Stand with your feet facing forwards parallel to your pelvis or with your legs turned out slightly (up to a maximum of 10°).

- Grasp a barbell with an appropriate weight in the overhand grip, i.e. the palms of the hands gripping the barbell point towards the body, or alternatively two dumbbells (see details).

- Hold your legs straight with a certain amount of force and press your entire forefoot firmly onto the floor. Slowly bend your hips into flexion with your back straight but not overstretched, as far as the flexibility of the back of your legs allows. If the floor can be reached with the dumbbells or barbell, keep the arms bent in the elbow joints to prevent this.

- Slowly stretch the hip joints again by the forve of the hamstrings (and secondarily the glutes) back to approx. 20° before the stretched angle.

- Perform the flexion and extension in the hip joints for as long as the pose can be performed cleanly with the back straight.

Details

- Of course, this is not a classic yoga pose, even if there is a certain similarity to entering and exiting the rectangular uttanasana. However, this pose is of great general and specific value as it can strengthen large parts of the back of the body beyond what is possible with your own weight: calf muscles (triceps surae), hip extensors (hamstrings and glutes), autochthonous back muscles (in their function as extensors of the spine). For the hamstrings in particular, it can provide good strengthening, which can be helpful in stabilising and recovering the knee joint in the event of damage. The autochthonous back muscles, especially in terms of their function as extensors of the spine, can also be strengthened very well, as the external weight on the upper extremity and the resulting long lever arm from the hip joint to the centre of mass of the upper body, head and arms must be counteracted with weight by an increasingly large torque in the vertebral segments in the direction of the lumbar spine. This design also explains the excellent strengthening of the hamstrings.

- Two dumbbells can also be used instead of a barbell. The overhand grip used with a barbell can be modified to a parallel hand position so that the dumbbells are parallel in the longitudinal direction, i.e. the palms are facing each other.

- It takes some experience or control to keep the back strictly straight according to the physiological lordosis in the lumbar spine and not to bend or hyperlordose in the lumbar spine. When practising alone, a mirror in which the back is checked closely or continuously is a good control. External control is described in the next variant.

- If the hip joints are bent in the direction of the horizontal of the pelvis, the lever arm does not change, but the „horizontal lever arm“ does, as the effect of gravity increases in the direction of the horizontal of the upper body in accordance with the angle functions. This increases the force with which the weight is pulled towards the floor and, accordingly, the force to be exerted in the hamstrings. In the same way, the force with which the calves must support increases. So create the conditions for a stable stance and, if possible, perform the pose barefoot on a hard, firm surface. A thin yoga mat is ideal for this. As the lever increases, the tendency of the back to curve in a convex direction and the force required to straighten it also increases. A selected weight is too great if the back cannot be kept straight in all relevant angles of flexion in the hips. The flexibility of the biarticular and only very secondarily the monoarticular hip extensors must be taken into consideration. Firstly, use a very light weight to determine how far the hip joints can be flexed without losing the physiological lordosis of the lumbar spine. Then perform the movement with increasing weight beginning with 20° of hip flexion each time up to the maximum to be determined.

With increasing movement of the back towards the horizontal, the „horizontal lever“ increases, so that more work is required from the hamstrings, the calves and the autochthonous back muscles. At a certain, individual point, a state of equilibrium is reached between the lever resulting from the upper partial body weight and the lever resulting from the pull of the hamstrings. From this point onwards, the hip flexors must be used with rapidly increasing force for further hip flexion, otherwise the physiological lordosis of the lumbar spine cannot be maintained. This effect must be perceived with the help of the perception of the lower back (proprioception) and reacted to accordingly. - The head is held in elongation of the spine or, if this does not lead to tension in the neck muscles, can be reclined, as this tends to promote extension of the thoracic spine.

- In order to keep the back straight in the sense of maintaining the physiological lordosis in the lumbar spine, it is necessary to tilt the pelvis just as quickly as the upper body is lowered; different speeds lead to a change in the shape of the back: if the pelvis is tilted faster than the upper body (and therefore the weight) is lowered, this results in hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine, which should of course be avoided. If, on the other hand, the pelvis is tilted more slowly than the weight is lowered, this results in a convex curve of the back.

- The hands, and with them the weight, are neither pushed away from the body nor pulled towards it. The arms hang vertically in the shoulder joints in line with gravity, with the shoulder blades neither protracted nor retracted too hard.

- Of course, there are other variations of the deadlift and this is certainly not the one in which the greatest weight can be moved, but it appears to be the most interesting in terms of movement physiology.

- The deadlift can be used to strengthen the structures of the hamstrings for those who are prone to irritation of the origin of the hamstrings (Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy, PHT) caused by excessive forward bending or other reasons (see FAQ). The unphysiological pain that occurs with this irritation is strictly avoided and the weight and range of motion (interval of the minimum to maximum flexion angle in the hip joints) is adjusted so that this pain does not occur, but good blood circulation and strengthening of the entire structures is achieved through a large number of repetitions. To do this, the maximum flexion angle that can still be achieved without pain is again determined with the lightest weight and the exercise is started with this light weight. Each time the weight is increased, the maximum pain-free flexion angle must be determined anew, as the pain depends on the angle and load. In any case, the aim of this procedure is not to move heavy weights in order to achieve great strength, but to promote healing by means of countless repetitions. Increasing the weight over time is therefore a secondary goal as long as the disorder is clearly present. Later, a „reserve capacity“ can be carefully developed with further increased weights as a preventative measure, which offers a helpful distance from the demands of everyday life, asanas and sports. According to current knowledge, however, a more offensive approach is possible and leads more quickly to success in insertional tendopathies: during rehabilitative training of the disturbed structure, pain equivalent to up to NRS 3 or 5 can be permitted, on condition that no reverberation occurs or that it has disappeared by the next day and that the discomfort does not increase over the exercise sessions.

- Depending on your constitution and knee health, particular care must be taken with the last degree of flexion in the hip joints. The weight naturally pulls much further into the stretch than you can get into uttanasana from gravity alone, and depending on the weight you choose, even more than if you pull with your hands on the ankles or use your hip flexors.

- If you can hyperextend the knee joints, you should be all the more careful not to do so, as an external weight is added to the large partial body weight and therefore an even greater hyperextension moment can occur in the knee joints. A few degrees of flexion of the knee joints hardly diminish the effect of the exercise, but offer good protection against overextension.

Variations

Knees bent

Instructions

- Adopt the posture as described above, but perform it with the knee joints slightly bent. Keep the flexion of the knee joints as constant as possible during the exercise.

Details

- This variant is particularly suitable for those who want to use the knee joints, knee joints who can overstretch, which can be safely prevented here. The various effects of the exercise suffer very little as a result.

- The more the knee joints are flexed, the more the effect shifts from strengthening the ischiocrural group to strengthening the gluteus maximus. As increasing flexion also reduces the inhibitory effect of the ischiocrural group on the hip flexion decreases, the pelvis can then be tilted further forwards and downwards with the upper body, which sometimes and especially in the case of very less mobile ischiocrural group only enables good strengthening of the autochthonous back muscles in the area of the lumbar spine.

(P) with stick

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above. In addition, a supporter holds a stick of sufficient length in the centre of the back so that it rests against the sacrum and the thoracic spine. The thoracic spine should be stretched as far as possible so that the length of the stick resting on it is maximised. Due to the physiological lordosis in the lumbar spine, there is normally a gap between the vertebrae and the stick. This is filled with one or two fingers. The task of the performer is to maintain as even a pressure as possible on all three points of support during the movement: The thoracic spine, sacrum and the finger on the lumbar spine.

Details

- If the thoracic spine detaches from the stick, this is probably due to flexion of the spine, which results from not sufficiently conteracting the tractive force of the external weight with the erector spinae, in other words the shoulder area moves quicker then the pelvis tilts. If contact is lost in the lumbar spine, the lumbar spine becomes hyperlordotic because the pelvis has been tilted too quickly.

- The movement should be performed slowly enough so that the development in the position of the stick can be closely observed, communicated and reacted to.

- Of course, with further flexion in the hip joints, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the straightness of the back. On the one hand, this is due to the increasing effect of gravity which increases from pelvis to shoulders, i.e. the increasing flexor moments in the vertebral segments; on the other hand, the hamstrings puts up more and more resistance to the tilting of the pelvis as their tension increases. At a certain point, the gravitational effect of the upper body, including the head, arms and external weight, is no longer sufficient to tilt the pelvis in line with the upper body position, even with the best possible extension of the back, and the back must begin to curve, which must lead to the loss of a contact point of the rod. Even before this, the required effort of the autochthonous back muscles continues to increase.

- At the beginning of the pose, when the stick is applied in standard anatomical position, flexibility restrictions of the hip flexors may become apparent, as the performer is unable to reduce the hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine to such an extent that the back comes to rest against the fingers in the lumbar spine. The reason for this is that shortened hip flexors iliopsoas and rectus femoris tilt the pelvis forwards into flexion in the hip joints and, in addition to this effect, the psoas major pulls the lumbar spine forwards and downwards and thus into hyperlordosis. The effect of the first two hip flexors alone would already result in hyperlordosis when the upper body is otherwise held upright, but the specific effect of the psoas major makes this even more difficult. The assumption of shortened hip flexors is confirmed if the hyperlordosis can be eliminated after just a few degrees of flexion in the hip joints, so that it is possible to place the back against the fingers on the stick in the lumbar spine area.