yogabook / effects

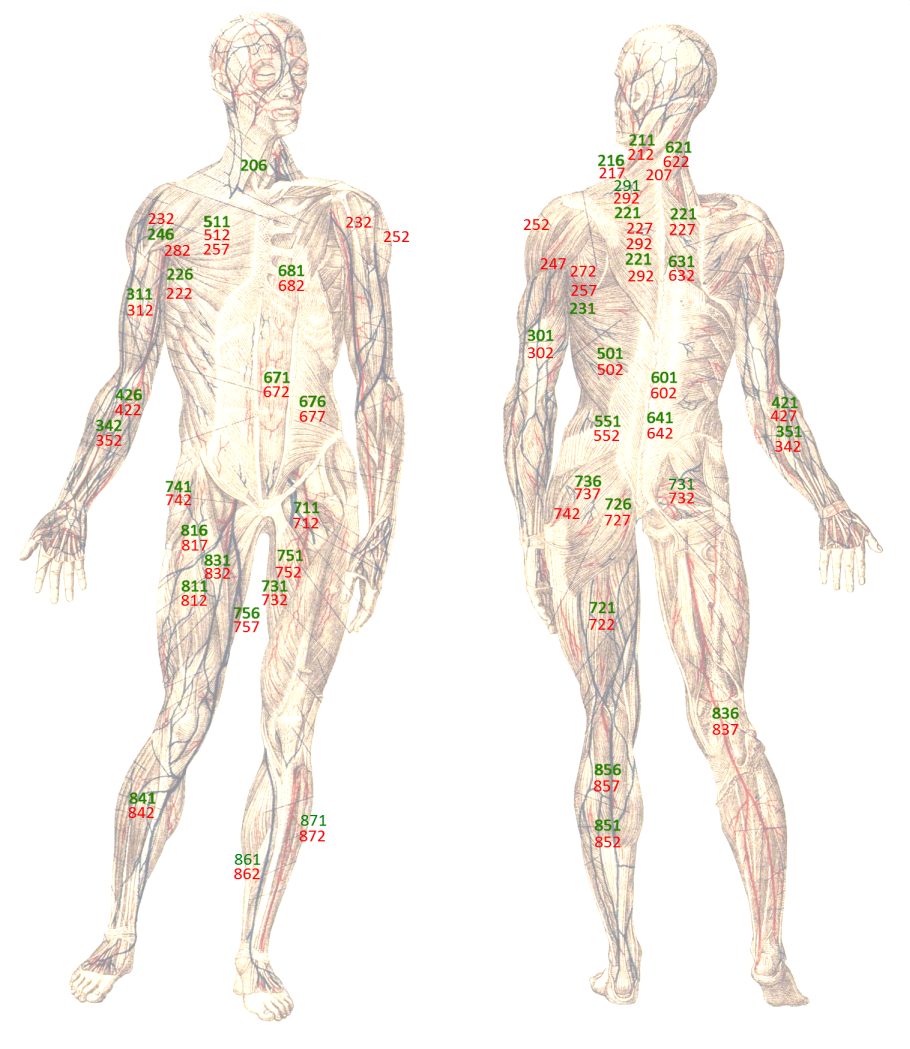

The effects of the poses on the musculature of the musculoskeletal system are described below. Wherever possible, asanas that achieve this effect are indicated. Click on the map and then on the body region that interests you, or scroll through the effects below. Green numbers on the map represent stretching, red numbers represent strengthening. A ventral and a dorsal view of the human body should make it possible to find all the important effects quickly.

Contents

- 1 201 Stretching the neck / cervical spine for flexion

- 2 202 Strengthening the neck / cervical spine for flexion:

- 3 206 Stretching the neck / cervical spine for reclination

- 4 207 Strengthening the neck / cervical spine for reclination:

- 5 211 Stretching the neck for rotation:

- 6 212 Strengthening the neck for rotation:

- 7 216 Stretching the neck for lateral flexion:

- 8 217 Strengthening the neck for lateral flexion:

- 9 221 Shoulder blade – stretching for protraction:

- 10 222 Shoulder blade: strengthening for protraction:

- 11 226 Shoulder blade: stretching for retraction:

- 12 227 Shoulder blade: strengthening for retraction:

- 13 231 Shoulder: stretching for frontal abduction:

- 14 232 Shoulder: Strengthening for frontal abduction:

- 15 241 Shoulder joint: stretching for frontal adduction:

- 16 242 Shoulder: Strengthening for frontal adduction:

- 17 246 Shoulder joint: stretching for retroversion:

- 18 247 Shoulder: strengthening for retroversion:

- 19 251 Shoulder: stretching for lateral abduction

- 20 252 Shoulder joint: strengthening for lateral abduction

- 21 256 Shoulder joint: stretching for lateral/transverse adduction

- 22 257 Shoulder: Strengthening for lateral/transverse adduction

- 23 271 Shoulder joint: stretching for external rotation

- 24 272 Shoulder joint: strengthening for external rotation

- 25 281 Shoulder joint: stretching for internal rotation

- 26 282 Shoulder joint: strengthening for internal rotation

- 27 291 Stretching the trapezius:

- 28 292 Strengthening the trapezius:

- 29 301 Stretching the triceps:

- 30 302 Strengthening the triceps:

- 31 306Stretch the biarticular triceps:

- 32 307 Strengthening the biarticular triceps

- 33 311 Stretching the biceps:

- 34 312 Strengthening the biceps:

- 35 321 Stretching to supination of the forearm:

- 36 322 Strengthening for supination of the forearm:

- 37 331 Stretching to pronate the forearm:

- 38 332 Strengthening for pronation of the forearm:

- 39 341 Stretching the dorsiflexors of the forearm (stretching the extensors):

- 40 342 Strengthening for dorsiflexion (strengthening the extensors):

- 41 351 Stretching the palmar flexors:

- 42 352 Strengthening the palmar flexors:

- 43 371 Stretching to elevate the shoulder blade:

- 44 372 Strengthening for elevation of the shoulder blade:

- 45 376 Stretching for depression of the shoulder blade:

- 46 377 Strengthening for depression of the shoulder blade:

- 47 381 Stretch for external rotation of the shoulder blade:

- 48 382 Strengthening for external rotation of the shoulder blade:

- 49 386 Stretch for internal rotation of the shoulder blade:

- 50 387 Strengthening for internal rotation of the shoulder blade:

- 51 390 Dyskinesia of the scapula:

- 52 411 Stretching for dorsiflexion in the wrist:

- 53 412 Strengthening for dorsiflexion of the wrist:

- 54 416 Stretching for palmar flexion in the wrist:

- 55 417 Strengthening for palmar flexion in the wrist:

- 56 421 Stretching the finger flexors:

- 57 422 Strengthening the finger flexors:

- 58 423 Tone of the finger flexors:

- 59 426 Stretching the finger extensors:

- 60 427 Strengthening the finger extensors:

- 61 428 Tone of the finger extensors:

- 62 501 Stretching the latissimus dorsi:

- 63 502 Strengthening the latissimus dorsi:

- 64 511 Stretching of the pectoralis major:

- 65 512 Strengthening the pectoralis major:

- 66 551 Stretching the quadratus lumborum:

- 67 552 strengthening the quadratus lumborum:

- 68 601 Stretching of the erector spinae:

- 69 602 Strengthening the erector spinae:

- 70 621 Stretching the (autochthonous muscles in the area of) the cervical spine:

- 71 622 Strengthening the (autochthonous muscles in the) cervical spine:

- 72 631 Stretching the (autochthonous muscles in the area of) the thoracic spine:

- 73 632 Strengthening the (autochthonous muscles in the area of) the thoracic spine:

- 74 641 Stretching the (autochthonous muscles in the) lumbar spine:

- 75 642 Strengthening the (autochthonous muscles in the) lumbar spine:

- 76 661 Spine: stretching for rotation

- 77 662 Spine: strengthening for rotation

- 78 666: Spine: stretching for lateral flexion

- 79 667 Spine: strengthening for lateral flexion

- 80 671 Abdominal muscles: Stretching the rectus abdominis:

- 81 672 Abdominal muscles: Strengthening the rectus abdominis:

- 82 676 Stretching the oblique abdominal muscles obliqui abdomini:

- 83 677 Strengthening the oblique abdominal muscles obliqui abdomini:

- 84 681 Stretching the intercostal muscles:

- 85 682 Strengthening the intercostal muscles:

- 86 711 Stretching the hip flexors:

- 87 712 Strengthening the hip flexors:

- 88 721 Stretching of the hamstrings:

- 89 722 Strengthening the hamstrings:

- 90 726 Stretching the short/monoarticular hip extensors:

- 91 727 Strengthening the short/monoarticular hip extensors:

- 92 731 Stretching the end rotators of the hip joint:

- 93 732 Strengthening the internal rotators of the hip joint:

- 94 736 Stretching the external rotators of the hip joint:

- 95 737Strengthening the external rotators of the hip joint:

- 96 741 Stretching the abductors:

- 97 742 Strengthening the abductors:

- 98 751 Stretching the adductors:

- 99 752 Strengthening the adductors:

- 100 756 Elongation the gracilis:

- 101 757 Strengthening the gracilis:

- 102 811 Stretching the quadriceps:

- 103 812 Strengthening the quadriceps:

- 104 813 Strengthening the vastus medialis

- 105 816 Stretching of the rectus femoris:

- 106 817 Strengthening the rectus femoris:

- 107 821 Stretching of the hamstrings as external rotators of the knee joint:

- 108 822 Strengthening the hamstrings as external rotators of the knee joint:

- 109 826 Stretching of the inner hamstrings as internal rotators of the knee joint:

- 110 827 Strengthening the inner hamstrings as internal rotators of the knee joint

- 111 831 Stretching of the Sartorius:

- 112 832 strengthening the sartorius:

- 113 836 Stretching of the popliteus:

- 114 837 Strengthening the popliteus:

- 115 841 Stretching the dorsiflexors of the foot:

- 116 842 Strengthening the dorsiflexors of the foot:

- 117 851 Stretching the foot extensors (plantar flexors / calf muscles):

- 118 852 Strengthening the plantar flexors (plantar flexors / calf muscles):

- 119 856 Stretching of the gastrocnemius:

- 120 857 Strengthening the gastrocnemius:

- 121 861 Stretching the supinators of the ankle:

- 122 862 Strengthening the supinators of the ankle:

- 123 871 Stretching the pronators of the ankle:

- 124 872 Strengthening the pronators of the ankle:

- 125 971 Stretching the toe flexors:

- 126 972 Strengthening the toe flexors:

- 127 981 Stretching the toe extensors (toe extensors):

- 128 982 Strengthening the toe extensors (toe extensors):

201 Stretching the neck / cervical spine for flexion

As the cervical spine is a „potential weak point“ in the construction of the human body, a more defensive approach should be taken here with strengthening and stretching, all the more so if it is suspected of being pre-damaged. Specialist clarification should then be sought. This applies even more to stretching than to strengthening. If there is a suspicion of disc prolapse or protrusion in the cervical spine, these stretches are contraindicated.

Asanas: – karnapidasana – halasana – sarvangasana – setu bandha sarvangasana – chakrasana

See also:

202: Strengthening the cervical spine muscles in the direction of flexion

glossary: Flexion of the cervical spine

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 201

202 Strengthening the neck / cervical spine for flexion:

Strengthening should also be approached a little more defensively, especially if the cervical spine is suspected of being pre-damaged. Specialist clarification should then be sought. Strengthening and stretching should be less intensive and more long-term. Strengthening the flexors of the cervical spine is primarily achieved in postures in which the face points approximately towards the ceiling and the head is held in a more or less horizontal position against the effect of gravity. Alternating between loading and unloading, i.e. lifting and lowering the head according to gravity, also achieves good results. Another way of strengthening is to press the head to the floor in a prone position. To ensure that the cervical spine does not have to be bent significantly due to the disturbing nose, it is advisable to place an object on the floor that is a few centimetres thick, still comfortable and only moderately compressible, against which the head is pressed.

Asanas: – purvottanasana (when the head is held horizontally) – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) (when the head is raised) – ustrasana (when the head is actively (more or less) raised)

See also:

201: stretching the cervical spine muscles in the direction of flexion glossary: flexion of the cervical spine

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 202

206 Stretching the neck / cervical spine for reclination

Stretching in the direction of reclination of the cervical spine is often neglected, which can lead to imbalances in the cervical spine. It may be necessary to start practicing this carefully and in small doses, rather over a longer period of time. Purvottanasana is ideal in all variations, especially for the beginning, as the head sinks into reclination purely due to the effect of gravity and no antagonistic muscles need to be used in addition to the stretched muscles, which could possibly develop a tendency to spasm. To a lesser extent, this also applies to urdhva dhanurasana (back arch), especially if the flexibility of the shoulder joints is not yet particularly pronounced but the pose can be held for a short time.

Asanas: – purvottanasana – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) (only slightly effective with good flexibility)

See also:

207: strengthening the cervical spine muscles towards reclination

glossary: reclination

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 206

207 Strengthening the neck / cervical spine for reclination:

The strength for reclination essentially comes from the autochthonous neck muscles. Strengthening in particularly short sarcomere lengths must be avoided if the muscles become subjectively uncomfortably toned. This can be the case with matsyasana, for example. Similarly, strengthening under long sarcomere lengths, such as in the right-angled shoulder pose, is only recommended with caution and only for advanced performers. Aautochthonous back muscles in the cervical spine and trapezius have more the character of „holding“ muscles than fast-moving muscles. The exercise pressing the head to the floor is well suited and tolerated.

Asanas: – press your head to the floor – matsyasana (if you can tolerate the short sarcomere length ) – right-angled shoulder stand (only recommended for experienced performers)

See also:

206: stretching the cervical spine muscles in the direction of reclination

glossary: reclination

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 207

211 Stretching the neck for rotation:

The rotation of the cervical spine and thus the rotational movement of the head relative to the trunk is mainly due to the effect of gravity or the work of the autochthonous muscles. The contralateral musculature is relaxed or stretched, depending on the intensity of the rotation. If the upper body also rotates, the opposite rotation of the cervical spine can cause a more intensive stretch than the same direction. This applies to many postures, for example jathara parivartanasana, in which the head can rotate in the opposite direction to the rotation of the upper body, largely in accordance with gravity. to

Asanas: – Drehsitz (parivrtta sukhasana) – trikonasana – ardha chandrasana – parivrtta trikonasana – parivrtta ardha chandrasana – parsvakonasana – parivrtta parsvakonasana – jathara parivartanasana (largely gravity-induced rotation) – maricyasana 1 – maricyasana 3 – savasana mit rotiertem Kopf (largely gravity-induced rotation) – ardha vasisthasana – vasisthasana – parivrtta uttanasana

Siehe auch:

212: strenghtning the cervical spine muscles in rotation

glossary: rotation of the spine

glossary : rotation of the head

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 211

212 Strengthening the neck for rotation:

As already described in 211, the two sides of the rotationally active autochthonous musculature are (partially) antagonistic. In contrast to stretching, strengthening of the rotationally active muscles in the cervical spine is rarely successful against the effect of gravity, as the effective lever arm is too small. After all, the human body has adapted to the upright gait in such a way that the gravity plumb line of the head in standard anatomical position lies approximately in the middle of the foramen magnum and thus on the axis of rotation of the head. Without reclination or flexion of the cervical spine, there is no lever arm. Strengthening against the tension of the antagonists, which is not constant but becomes higher the more forcefully the agonists are used, is more favorable. This provides an effective mechanism for strengthening. However, care must be taken to ensure that the antagonists do not go into spasm. If there is any sign of a cramp, immediate intervention must be made by reducing the intensity or changing another parameter. If necessary, the posture must be interrupted. In the standing postures listed below, the parivrtta variations generally allow the more pronounced strengthening compared to the utthita variations because the upper body, depending on its flexibility, can rotate less far in the vertical direction.

Asanas: – sitting twist (parivrtta sukhasana) – trikonasana – ardha chandrasana – parivrtta trikonasana – parivrtta ardha chandrasana – parsvakonasana – parivrtta parsvakonasana – jathara parivartanasana (largely gravity-induced twist) – maricyasana 1 – maricyasana 3 – ardha vasisthasana – vasisthasana – parivrtta uttanasana

See also:

211: stretching the cervical spine muscles in rotation

glossary: rotation of the spine

glossary: rotation of the head

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 212

216 Stretching the neck for lateral flexion:

Stretching the cervical spine in the direction of lateral flexion is best achieved by gravity, as some of the agonists usually work in such short sarcomere lengths during muscle-induced stretching that they begin to spasm. Postures in which the longitudinal axis of the head is inclined between horizontal and about 20/30° to the horizontal and the face points in a roughly horizontal direction, as is the case in trikonasana without turning the head, are therefore suitable. From this position, the head is then lowered into a lateral flexion according to gravity.

Asanas: – trikonasana (when the head is lowered according to gravity) – ardha chandrasana (when the head is lowered according to gravity) – vasisthasana (when the head is lowered according to gravity) – ardha vasisthasana (when the head is lowered according to gravity) – parsvakonasana (when the head is lowered according to gravity)

See also:

217: strengthening the cervical spine muscles towards lateral flexion

glossary: lateral flexion (side bend)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 216

217 Strengthening the neck for lateral flexion:

The main postures available for strengthening the lateral flexor parts of the autochthonous musculature are those that work with the gravitational force of the head. This means that the strengthening options are limited and tend more towards strength endurance than gravity. Postures in which the head has to be held more or less horizontally against the effect of gravityare suitable.

Asanas: – trikonasana – ardha chandrasana – vasisthasana – ardha vasisthasana – parsvakonasana

Siehe auch:

216: stretching the cervical spine muscles in direction of lateral flexion

glossary: lateralflexion (sideband)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 217

221 Shoulder blade – stretching for protraction:

The main muscles involved are the serratus anterior (direct) and pectoralis major (indirect, via the upper arm). These muscles are used to stabilize the shoulder blade during all forward-pushing movements, such as the bar. Garudasana is particularly suitable for stretching the antagonisticretractors such as the rhomboids. Secondarily, if the retractors are significantly shortened, all postures that lateralize the shoulder blades are suitable.

Asanas: – garudasana – elbow stand – caturkonasana – ellbow downface dog – rectangular elbow stand – shoulder opening at the chair – staff pose

Siehe auch:

222: strengthening the protractors of the shoulder blade

glossary: protraction of the scapula

glossary: protractors of the scapula

glossary: retraction of the shoulder blade (counter movement)

glossary: retractors of the scapula (antagonist)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 221

222 Shoulder blade: strengthening for protraction:

The serratus anterior (direct) and pectoralis major (indirect, via the upper arm) protractors are used firstly to stabilize the position of the scapula in all forward-pushing movements. Secondly, they are also used to lateralize the scapula, for example to support a large partial body weight against a surface, such as in vasisthasana, or thirdly without external resistance in the 2nd warrior pose. Of the three cases mentioned, the greatest strengthening is possible in the first case, followed by the second case. In the last case, no significant strengthening can usually be achieved.

Asanas: – staff pose – vasisthasana – ardha vasisthasana

Siehe auch:

221: Stretching the protractors of the shoulder blade

glossary: protraction of the shoulder blade

glossary: protractors of the shoulder blade

glossary: retraction of the shoulder blade (antagonistic movement)

glossary: Retraktoren des Schulterblattes (antagonist )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 222

226 Shoulder blade: stretching for retraction:

The powerfully protracting serratus anterior (direct) and pectoralis major (indirect, via the upper arm) muscles in particular can limit retraction. In addition to occupational and sporting activities, incorrect posture with protracted shoulderblades often contributes to this. Stretching of the protractors usually occurs with retroverted arms, so that stretching sensations can also occur in the pars clavicularis of the deltoid.

Asanas: – namaste on the back – trikonasana, variation: hand on the inner leg – trikonasana, variation: block in the hand, option: sinking backwards – purvottanasana – gomukhasana

See also:

227: strengthening the retractors of the scapula

glossary: retraction of the scapula

glossary: retractors of the scapula

glossary: protraction of the scapula (countermovement)

glossary: protractors of the scapula (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 226

227 Shoulder blade: strengthening for retraction:

While the retractors are often used in sports, e.g. for rowing movements or tug-of-war, they are mainly used in asanas to stabilize the shoulder blade, for example in jathara parivartanasana to prevent the upper body from tipping sideways. Because of the great leverage provided by the two legs, this offers a good opportunity for strengthening. The pulling movement on the contralateral knee also offers an opportunity to strengthen the retractors in twist pose.

Asanas: – jathara parivartanasana – twisting pose (parivrtta sukhasana )

See also:

226: stretching the retractors of the scapula

glossary: retraction of the scapula

glossary: retractors of the scapula

glossary: protraction of the scapula (countermovement)

glossary: protractors of the scapula (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 227

231 Shoulder: stretching for frontal abduction:

The effect of postures to promote frontal abduction depends on the rotational situation of the upper arm: arms that are turned out further are more effective than arms that are turned out less, so the derivations of the elbow position and the shoulder opening on the chair are the first choice here. This becomes clear when looking at the insertion of the most important restricting muscles, both of which are internal rotating adductors of the shoulder joint: teres major and latissimus dorsi

Asanas: – gomukhasana – hyperbola – raised back extension – downface dog – downface dog wide – urdhva dhanurasana – handstand – rectangular handstand – elbow stand – dog elbowstand – rectangular elbowstand – rectangular headstand – dvi pada viparita dandasana – eka pada viparita dandasana – shoulder opening on chair – caturkonasana – headstand – 1. Warrior pose – lying on a roll – parsvakonasana – parivrtta parsvakonasana – back stretch – raised back stretch – supta virasana – upavista konasana with block – ustrasana: arms stretched overhead (urdhva hastasana) – ustrasana: lean back like a plank – parsvautkatasanakonasana – uttanasana: (S) straighten back

See also:

232: Strengthening the frontal abduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: frontal adductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 231

232 Shoulder: Strengthening for frontal abduction:

In frontal abduction, the monoarticular deltoid (pars clavicularis) and coracobrachialis muscles work together with the biarticular biceps. When strengthening, a distinction must be made according to sarcomere length: in short sarcomere length, overhead postures such as handstand, downface dog, postures with turned out upper arms work even better; in medium sarcomere length, there are only a few postures that work with a greater load than the gravity of the arms, such as the three-point headstand. In the long sarcomere length and therefore particularly valuable is the intensive backward pressing head up dog position as well as the transitions between head up dog position and head down dog position and back, which have a unique selling point in the simultaneity of almost complete ROM, lack of a construction-related limitation of the use of force and alternating succession of concentric and eccentric contraction. In addition, the angle in the elbow joint and, to a lesser extent, the state of overrotation of the forearm(pronation/supination) also play a role in strengthening the frontal abductors due to the biarticular biceps.

Asanas: – upface dog – upface dog: dips – downface dog: transition to upface dog – headstand – threepoint headstand – staff pose – upavista konasana with a block – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch): dips – utkatasana

See also:

231: stretching for frontal abduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: frontal adductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Other positions with the impact indicator 232

241 Shoulder joint: stretching for frontal adduction:

Frontal adduction brings the arm from the frontally abducted position back towards standard anatomical position, so apart from hypothetical cases of a pathological nature, no special stretching is required to bring the arm into this position. However, if the arm is moved further dorsally, this is a retroversion that requires specific flexibility.

Asanas:

See also:

242: strengthening the frontal adduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: retroversion in the shoulder joint

glossary: retroverters of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: frontal abductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 241

242 Shoulder: Strengthening for frontal adduction:

Frontal adduction essentially requires the same muscles as those listed for retroversion, into which it merges seamlessly in Anatomical Zero, but here the pectoralis major is added. Frontal adduction and retroversion are mainly performed by the teres major, latissimus dorsi, the middle head of the triceps and the posterior head of the deltoid. In the case of the middle head of the triceps, the angle in the elbow joint and the rotation(internal rotation/external rotation) in the shoulder joint must be taken into account, as when the elbow joint is more or less extended, the triceps become very short in sarcomere length during retroversion, which easily causes it to spasm. This is exacerbated by turning out the upper arm. The head-up dog position with the feet turned over often shows this effect very clearly.

Asanas: – downface dog with the hands on a piece of carpet – uttanasana: table variation – back extension increased when the hands are pressed down firmly

See also:

241: stretching for frontal adduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: retroversion in the shoulder joint

glossary: retroverters of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: frontal abductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 242

246 Shoulder joint: stretching for retroversion:

Retroversion is hindered primarily by the anterior part of the deltoid and, if the arm is extended rather than flexed, also by the biceps. In addition, a shortened pectoralis can also limit movement, especially if the arm is turned out, as the pectoralis turns in the arm. The other frontal abductor muscle, the coracobrachialis, hardly plays a role as a limiting muscle in practice.

Asanas: – purvottanasana – uttanasana with arms behind the body – prasarita padottanasana with arms behind the back – gomukhasana – namaste – karnapidasana – halasana – shoulder stand – parsvottanasana – setu bandha sarvangasana – trikonasana – uttanasana: Arms behind the body

See also: – 247: strengthening retroversion of the shoulder joint

glossary: fetroversion in the shoulder joint

glossary: fetroverters of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement) glossary: frontal abductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 246

247 Shoulder: strengthening for retroversion:

Retroversion is the continuation of frontal adduction and is mainly performed by the teres major, latissimus dorsi, the middle head of the triceps and the posterior head of the deltoid. In the case of the middle head of the triceps, the angle in the elbow joint and the rotation(internal rotation/external rotation) in the shoulder joint must be taken into account, as when the elbow joint is more or less extended, the triceps become very short sarcomere lengths in retroversion, which easily causes them to spasm. This is exacerbated by turning out the upper arm. The head-up dog position with the feet turned over often shows this effect very clearly.

Asanas: – upface dog with feet upside down – jathara parivartanasana – parivrtta trikonasana – ardha chandrasana – parivrtta ardha chandrasana – parivrtta parsvakonasana – maricyasana 3: press only with the arm against the thigh

See also:

246: Stretching for retroversion of the shoulder joint

glossary: retroversion in the shoulder joint

glossary: retroverters of the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal abduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: Frontal abductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 247

251 Shoulder: stretching for lateral abduction

The ability of the humerus to abduct laterally is clearly dependent on the rotation of the humerus: maximum abduction is only possible with more or less complete external rotation. In the internally rotated state, the joint structure does not allow lateral abduction to go much beyond 90°. Any further movement of the upper arm relative to the trunk would then come from the external rotation of the scapula. The 180° laterally abducted position with external rotation is identical to the 180° frontally abducted position. With good flexibility, however, further degrees of abduction are possible in both dimensions of movement, so that the limits are not identical. It is virtually impossible to differentiate precisely between postures that specifically promote frontal and lateral abduction, which is why reference is made here to the list of postures given under (231) to promote frontal abduction.

Asanas:

See also:

glossary: 252: Strengthening lateral abduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: Lateral abduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: Lateral adduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 251

252 Shoulder joint: strengthening for lateral abduction

lateral abduction is mainly performed by the supraspinatus during the first 90°, then by the deltoid and weakly by the long head of the biceps.

Asanas: – ardha vasisthasana – vasisthasana (when the supporting hand is pushed away from the feet) – parsvakonasana (when the supporting hand is pushed away from the feet) – 2nd warrior pose (rather weaker and in terms of endurance)

See also:

glossary: 251: stretching for lateral abduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral abduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral abductors of the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement) glossary: lateral adductors of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 252

256 Shoulder joint: stretching for lateral/transverse adduction

To achieve this stretch, the arm must be moved significantly and permanently medially, either actively, mainly through the strength of the pectoralis major, which then tends to develop a tendency to spasm in a very short sarcomere length close to active insufficiency, or passively by constructing the posture as in garudasana. In this pose, the movement of the arm is due to both the lateral adduction of the arm and the protraction of the scapula.

Asanas: – garudasana

See also:

257: strengthening lateral adduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adductors of the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral abduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement) – glossary: lateral abductors of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 256

257 Shoulder: Strengthening for lateral/transverse adduction

Lateral adduction (also known as transverse adduction) is mainly performed by the powerful biarticular latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major muscles, which originate from the trunk. The teres major and teres minor muscles originating from the shoulder blade also play a role, as do the upper arm muscles biceps with its short head, triceps with its middle head and coracobrachialis. The pars spinalis and clavicularis of the deltoid also adduct, while the pars acromialis can only abduct. Of the muscles belonging to the so-called rotator cuff, the subscapularis adducts, while the infraspinatus abducts with its cranial parts and adducts with more caudal parts. In other words, all strengthening of the muscles mentioned increases the force with which adduction can be performed. If the upper arm is to be adducted beyond neutral zero, a distinction must be made between adduction in front of and behind the trunk. When adducting behind the trunk, the latissimus dorsi and the pars spinalis of the deltoideus work well, while the pectoralis major and the pars clavicularis of the deltoideus tend to be more restrictive; similarly, adduction in front of the rib cage is performed by the pectoralis major and pars clavicularis of the deltoideus, while the latissimus dorsi and pars clavicularis of the deltoideus tend to be more restrictive.

Asanas: – ardha vasisthasana (stabilizing, rather less effective) – staff pose

See also:

glossary: 256: stretching for lateral abduction of the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adductors in the shoulder joint

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: lateral abductors in the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 257

271 Shoulder joint: stretching for external rotation

To improve the ability to externally rotate in the shoulder joint, the antagonistic internal rotators must be stretched. The strongest of these are the subscapularis, followed by the pectoralis major, which is also quite strong, the teres major, pars clavicularis of the deltoid and, rather weakly, the biceps. The greatest restrictions on external rotation are to be expected from the pectoralis major and, to a lesser extent, the teres major, although this depends on the angles of lateral abduction and frontal abduction. The ability to externally rotate decreases with increasing frontal abduction and usually also with transverse abduction. As many postures have externally rotated arms, those that externally rotate the arms more powerfully are indicated in particular.

Asanas: – dog elbow pose – right-angled elbow pose – elbow pose – shoulder opening on the chair – garudasana

See also:

272: strengthening for external rotation of the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotation in the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotators of the shoulder joint

glossary: internal rotation in the shoulder joint (countermovement) – glossary: internal rotators of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 271

272 Shoulder joint: strengthening for external rotation

Although many poses have rotated arms, there are hardly any asanas that exercise the strength of the external rotators during the pose; only when assuming dog elbow pose from downface dog is the arm rotated with force, which is also performed by internally rotating adductor muscles of the shoulder joint such as the pectoralis major due to the fixed hands.

Asanas: – handstand – upface dog – downface dog – downface dog: Transition to dog elbow stand

Siehe auch:

glossary: 271: stretching for external rotation of the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotation in the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotators of the shoulder joints

glossary: internal rotation in the shoulder joint (antagonistic movement)

glossary: internal rotators of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 272

281 Shoulder joint: stretching for internal rotation

The improvement in internal rotation ability is achieved by stretching the muscles that cause external rotation. These are the teres minor, infraspinatus and pars spinalis of the deltoid. They are less powerful than the internal rotators and also less powerful in total, but sports with throwing movements can lead to an internal rotation deficit (GIRD).

Asanas: – maricyasana 1 – maricyasana 3 – trikonasana with hand on the inner leg – namaste on the back – gomukhasana

See also:

282: Strengthening for internal rotation of the shoulder joint

glossary: internal rotation in the shoulder joint

glossary: internal rotators of the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotation in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: external totators of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 281

282 Shoulder joint: strengthening for internal rotation

Subscapularis, then the pectoralis major, which is also quite strong, the teres major, pars clavicularis of the deltoideus and, rather weakly, the biceps. The greatest restrictions on external rotation are to be expected from the pectoralis major and, secondarily, the teres major, although this depends on the angles

Asanas: – namaste (when performed with strength ) – namaste on the back (when performed with strength )

See also:

glossary:

281: Stretching for internal rotation of the shoulder joint

282: Strengthening for internal rotation of the shoulder joint

glossary: internal rotation in the shoulder joint

glossary: internal rotators of the shoulder joint

glossary: external rotation in the shoulder joint (countermovement)

glossary: external rotators of the shoulder joint (antagonists)

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 282

291 Stretching the trapezius:

Due to its course, the trapezius is less easy to stretch than many other muscles of the musculoskeletal system. As all three parts attach to the spina scapulae (scapular spine), they benefit from the lateralization or protraction of the depressed (pars descendens) or elevated (pars ascendens) scapula for stretching. The subjectively greatest need for stretching is regularly in the upper (for the pars descendens) and middle (for the pars transversum) part of the trapezius. If the stretching effect is not sufficient when the shoulder blade is maximally lateralized, additional pressure must be exerted transversely to the course of the muscle. The pars ascendens of the trapezius is an important shoulder blade depressor, which means that all overhead postures with anelevated shoulder blade, those in which the upper body moves away from fixed hands in accordance with gravity, e.g. raised back extension, hyperbola, stretch it significantly more than those in which the pars descendens of the trapezius performs this work, e.g. downface dog, handstand. See also the postures listed under stretching frontal abduction, which stretch the pars ascendens due to their elevatedshoulder blade.

Asanas: – head side bend – karnapidasana on rolls – shoulder stand – halasana – karnapidasana – 2nd warrior pose

See also:

292: Strengthening the trapezius

glossary: trapezius

glossary: protraction of the scapula

glossary: retraction of the scapula

glossary: depression of the scapula

glossary: elevation of the scapula

glossary: external rotation of the scapula

glossary: internal rotation of the scapula

glossary: scapula

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 291

292 Strengthening the trapezius:

Pars descendens is strengthened by overhead postures with the shoulder blade elevated, preferably against the body’s gravity, such as in a handstand. For this part, see the postures listed under frontal abduction of the shoulder joint. Pars ascendens of the trapezius is an important shoulder blade depressor, so all postures that depress the shoulder blade strengthen it. Pars transversa is strengthened in jathara parivartanasana when maintaining the protraction of the shoulder blades.

Asanas: – downface dog (Pars ascendens) – downface dog (Pars decendens) – tolasana (Pars descendens) – handstand (Pars descendens) – rectangular handstand (Pars descendens) – elbow stand (Pars transversa) – jathara parivartanasana (Pars transversa)

See also:

291: stretching the trapezius

glossary: trapezius

glossary: protraction of the scapula

glossary: retraction of the scapula

glossary: depression of the scapula

glossary: elevation of the scapula

glossary: external rotation of the scapula

glossary: internal rotation of the scapula

glossary: depression of the scapula

glossary: elevation of the scapula

glossary: external rotation of the scapula

glossary: internal rotation of the scapula

glossary: scapula

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 292

301 Stretching the triceps:

In the triceps, a distinction must be made between the middle, biarticular part, which also performs the retroversion of the arm, and its two monoarticular neighboring heads, which only stretch the elbow joint. All are stretched by wide flexion of the elbow joint, but this should not be done under heavy load. A wide frontal abduction in the shoulder joint is also required to stretch the middle head. By far the best posture for stretching is gmokukhasana, which stretches both the monoarticular heads (both arms) with complete flexion of the elbow joints and the biarticular head (upper arm) through very wide frontal abduction.

Asanas: – gomukhasana

See also:

302: strengthening the triceps

glossary: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint

glossary: biceps (most important antagonist )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 301

302 Strengthening the triceps:

The triceps are strengthened in all three heads when the elbow joint is extended, whereby the extension should not be performed from a maximally or almost maximally flexed elbow joint. In addition, actively performed retroversion in the shoulder joint strengthens the middle head of the triceps, such as in upface dog with feet turned over. The sustained stabilization of the three-point headstand also has a strengthening effect.

Asanas: – staff pose – downface dog: transition to staff pose and back – downface dog: dips – handstand: dips – urdhva dhanurasana: dips – upface dog with stretched feet – bhujangasana – jathara parivartanasana

See also:

301: stretching the triceps

glossary: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint

glossary: biceps (most important antagonist )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 302

306Stretch the biarticular triceps:

In the triceps, a distinction must be made between the middle, biarticular part, which also performs the retroversion of the arm, and its two neighboring heads, which only stretch the elbow joint. All are stretched by wide flexion of the elbow joint, but this must not be done under a heavy load. Frontal abduction in the shoulder is also required to stretch the middle head.

Asanas: – gomukhasana

See also:

301: stretching the triceps

307: strengthening the biarticular triceps

302: strengthening the triceps

glossary: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint

glossary: biceps (most important antagonist )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 306

307 Strengthening the biarticular triceps

In addition to the postures mentioned under 302, the retroversion movement in the shoulder joint is particularly important here. This can generally be performed with the elbow joint flexed, for example with the forearms resting on the floor, but then only the biarticular middle head of the triceps is strengthened. For a more complete strengthening, postures with the elbow joint extended must be selected, such as upface dog with feet turned over. When the arms are rotated out, the elbow joint is not mechanically locked in the plane of the force vector during retroversion (which would place a load on the joint), but the monoarticular heads of the triceps must cancel the flexion moments in the elbow joint caused by the retroversion with the forearm or hands fixed, which causes them to work in a very short sarcomere length. As monoarticular heads, however, they should not have a tendency to spasm, unlike the biarticular head. However, the smaller the angle of frontal abduction in the shoulder joint and, moreover, the greater the angle of retroversion in the shoulder joint, the greater the tendency to spasm. The triceps are primarily strengthened when the elbow is extended, whereby the elbow should not be extended with the elbow flexed to the maximum or almost to the maximum. Active retroversion in the shoulder joint also strengthens the middle head of the triceps

Asanas: – upface dog with feet upside down – bhujangasana – jathara parivartanasana

See also:

307: strengthening the biarticular triceps

301: stretching the triceps

306: stretching the biarticular triceps

glossary: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint

glossary: biceps (most important antagonist )

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 307

311 Stretching the biceps:

As the biceps is biarticular in both heads, stretching it requires retroversion in the shoulder joint with the elbow joint extended or extension of the elbow joint in wide retroversion in the shoulder joint.

Asanas: – uttanasana: arms behind the body – prasarita padottanasana: arms behind the back – purvottanasana: all variations with outstretched arms – setu bandha sarvangasana with outstretched arms

See also:

312: strengthening the biceps

glossary: triceps (most important antagonist)

glossary: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint –

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 311

312 Strengthening the biceps:

There are few yoga poses for strengthening the biceps, as working against the body’s gravity (without a pull-up bar or similar) requires stretching and not flexing movements of the elbow joint. This means that the only resistance that can be used is your own body, i.e. the pull on the leg or foot in forward bends, and the use of the biceps in its function as an antevertor (frontal abductor).

Asanas: – upface dog – uttanasana mit Zug an den Unterschenkeln – Drehsitz – Bizeps anspannen – Schulterstand – setu bandha sarvangasana – janu sirsasana – ardha baddha padma postimottanasana – postimottanasana – tryangamukhaikapada postimottanasana – prasarita padottanasana mit aufgestützten Händen

Siehe auch: –

311: stretching the biceps

glossary: triceps (most important antagonist)

glossary: glossar: elbow joint

glossary: shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 312

321 Stretching to supination of the forearm:

There are no postures in which powerful pronation of the forearm takes place from or with the help of external forces that would stretch the supinators. The possibilities are limited to the stretch limited by the force exerted by the pronators. Postures such as downface dog, handstand, right-angled handstand, dog elbow stand, urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) achieve this. As the elbow joint is stretched in these poses, the longer supinators in particular are stretched. Postures with the elbow joint bent, such as elbow stand right-angled elbow stand, are used to stretch the shorter supinators in particular.

Asanas: – downface dog – handstand – right-angled handstand – dog elbow stand – elbow stand – right-angled elbow stand

See also:

322: strengthening the supinators of the forearm

glossary: supination of the forearm

glossary: supinators of the forearm (agonists)

glossary: pronation of the forearm (countermovement)

glossary: pronators of the for earm (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 321

322 Strengthening for supination of the forearm:

The grip on the lower leg to turn it and therefore the whole leg out in the hip joint enables the supinators to be strengthened in postures such as trikonasana standing against the wall, as part of the upper limb has to work against resistance from the lower limb. The situation is similar in hip opener 4.

Asanas: – trikonasana standing against the wall – hip opener 4

See also:

321: stretching the supinators of the forearm

glossary: supination of the forearm

glossary: supinators of the forearm (agonists)

glossary: pronation of the forearm (countermovement)

glossary: pronators of the forearm (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 322

331 Stretching to pronate the forearm:

A certain degree of stretching of the pronators is achieved with postures such as three-point headstand or prasarita padottanasana, in which the hands are placed on the floor in a supinated position. Other poses include namaste on the back and downface dog transition to staff pose, downface dog: Transition to dog elbow pose, which also require a certain amount of ulnar abduction. However, these postures hardly stretch the pronators, which originate at the medial conlylus, as the elbow joint is flexed in these postures. If these long pronators are to be included, the elbow joint must be more or less extended, as in urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) with inverted hands. In all the poses listed, there is no stretching beyond that caused by the hands once they are fixed at the beginning of the pose.

Asanas: – three-point headstand – prasarita padottanasana – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) with inverted hands

See also:

332: strengthening the pronators of the forearm

glossary: wrist

glossary: pronation of the forearm

glossary: pronators of the forearm (agonists )

glossary: supination of the forearm (countermovement)

glossary: supinators of the forearm (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 331

332 Strengthening for pronation of the forearm:

Trying to keep the base joints of the index fingers pressed to the floor offers the opportunity to strengthen the pronators in many postures with hands on the floor. Other, non-final strengthening exercises are not known except for the variations of the handstand and its derivatives, in which the hands are not turned forwards but to other angles.

Asanas: – downface dog – dog elbow stand – elbow stand – right-angled elbow stand – right-angled handstand – handstand with hands placed at different angles

See also:

331: stretching the pronators of the forearm

glossary: pronation of the forearm

glossary: pronators of the forearm (agonists)

glossary: supination of the forearm (countermovement)

glossary: supinators of the for earm (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Other positions with the impact indicator 332

341 Stretching the dorsiflexors of the forearm (stretching the extensors):

The classic way of stretching the dorsiflexors is dorsal forearm stretching, whereby the closed fists stretch the finger extens ors more than the actual (non-finger-moving) dorsiflexors. As a rule, a lot of work is required on the stretching ability of the finger extensors before the actual dorsiflexors can also be stretched in this posture. If the finger extens ors are to be bypassed, the fist must be opened. This usually increases the achievable angle of dorsiflexion by more than 10-20° and enables efficient stretching of the actual dorsiflexors. No other postures for stretching the dorsiflexors are known, which is due to the fact that leaning on the back of the hand is neither particularly physiological nor particularly comfortable.

Asanas: – dorsal forearm stretch with open fist

See also:

342: strengthening the dorsiflexion of the wrist

glossary: dorsiflexion of the hand

glossary: dorsiflexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand ( countermovement)

glossary: palmar flexors of the hand (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 341

342 Strengthening for dorsiflexion (strengthening the extensors):

In contrast to the palmar flexors, there is no asana that strengthens the dorsal flexors. For example, the back of the hand would have to be pressed against the floor, another object or a part of the body. At best, moderate strengthening can be achieved by gripping the lower leg with the hand in trikonasana and pulling the lower shoulder forward with a retroversion movement. This can be achieved much more effectively with functional weight training, for example with bicep curls in the overhand grip. This can also be used as light regenerative training for tennis elbow.

Asanas: – trikonasana wie oben beschrieben

Siehe auch:

341: stretching the dorsal flexors of the wrist

glossary: dorsal flexion of the hand

glossary: dorsal flexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand (countermovement)

glossary: palmar flexors of the hand (antagonists )

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 342

351 Stretching the palmar flexors:

The palmar flexors are stretched in various postures supported by the arms, such as head-up dog pose, right-angledhandstand and handstand. In urdhva dhanurasana, the angle of 90° dorsiflexion can also be significantly exceeded depending on shoulder flexibility. Another option is namaste on the back, in which the angle of 90° dorsiflexion can be exceeded if the hands are held lower than normal.

Asanas: – head up dog pose – right-angled handstand – handstand – namaste on the back – palmar forearm stretch in upavista konasana – palmar forearm stretch

See also:

352: strengthening the palmar flexors of the wrist

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand

glossary: palmar flexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: dorsiflexion of the hand ( countermovement)

glossary: dorsiflexors of the hand (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Other positions with the impact indicator 351

352 Strengthening the palmar flexors:

In addition to all postures supported on the floor and on the wall with a dorsiflexed wrist at around 90°, such as head-up dog pose, right-angled handstand and handstand, in which the dorsiflexors are used to achieve a stable posture on the one hand and a certain movement of the shoulder (in the direction of further frontal abduction) on the other, tolasana is also suitable, in which the balance work is performed by the palmar flexors, among others. These muscles also work continuously in the three-point headstand to maintain balance.

Asanas: – head up dog pose – right-angled handstand – handstand – tolasana – three-point headstand

See also:

351: stretching the palmar flexors of the wrist

352: strengthening the palmar flexors of the wrist

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand

glossary: palmar flexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: dorsiflexion of the hand (countermovement)

glossary: dorsiflexors of the hand (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Other positions with the impact indicator 352

371 Stretching to elevate the shoulder blade:

The ability to elevate the shoulder blades depends to a lesser extent on the flexibility of the direct depressors such as the trapezius pars ascendens and the pectoralis minor, which pull from the trunk to the shoulder blade and therefore only move in the scapulothoracic glenohumeral joint, but above all on the indirect depressors, which pull from the trunk via the scapulothoracic glenohumeral joint and the glenohumeral joint to the upper arm, such as the latissimus dorsi. The adductor muscles of the upper arm, which pull directly from the shoulder blade to the upper arm, such as the teres major and teres minor, do not play a role.

In all cases, the position of the arm plays a more or less pronounced role. If the upper arm is raised by at least 90° laterally or frontally (or mixed), the shoulder blade will have performed an external rotation, the further the abduction, the more. As a result, the muscles connected to the shoulder blade from the trunk are under a different tension than without external rotation. The rhomboids, even elevators, would not offer increased resistance to elevation, but the pars ascendens of the trapezius and caudal fibers of the serratus anterior would.

The influence of the position of the arm is much more pronounced in the case of the biarticular ( scapulothoracic glenohumeral joint) latissimus dorsi, which acts primarily as a lateral adductor and slight retrovertor from large parts of the dorsal trunk to the upper arm and can therefore represent a very significant restriction against elevation when the arms are raised. The influence of the pectoralis major will be somewhat less inhibitory, as it itself tends to contribute more initially to frontal abduction. In most cases in which the arm cannot be frontally abducted 180° or laterally abducted (with sufficient external rotation) when the shoulder blade is elevated, the latissimus dorsi is likely to set this restriction, just as it does when the shoulder blade can no longer be elevated in 180° abduction in one direction, or only to a very limited extent. This becomes even clearer if the restriction of elevation diminishes when leaving wide abduction.

In this category 371, all postures with 180° frontal abduction and elevated shoulder blade should be mentioned, a combination that can be found in many yoga postures, be it dog pose head down, urdhva hastasana, handstand, hyperbola or bridge.

Asanas: –

See also: – 372: –

Other positions with the impact indicator 371

372 Strengthening for elevation of the shoulder blade:

In this section, the same movement is performed as in 371, but with force, i.e. against a greater partial body weight. In the handstand, for example, the aim is to lift a partial body weight, which corresponds to the total body weight minus the two arms, approximately 1:1 against gravity. The limit of the movement is set softly and elastically, usually by the latissimus dorsi, more rarely by the pectoralis major. As explained above, these two biarticular muscles represent the greater restriction of movement compared to the monoarticular muscles that move the shoulder blade from the trunk. In terms of posture execution, this means that – if flexibility in the direction of frontal abduction is at least moderately good – an even and barely increasing development of force against the force of gravity occurs first, and then rapidly increasing forces are required for further lifting of the body, without a firm or hard limit being noticeable. On the other hand, the three-dimensional flexibility of the shoulder joint and the overlying muscles, which set a limit to movement here, result in evasive movements, i.e. in the two important biarticular indirect depressors of the shoulder blade, pectoralis minor and latissimus dorsi, an outward evasion of the upper arm and a reduction in external rotation.

The most important elevators are the pars descendens of the trapezius, which also performs the external rotation of the scapula required for wide frontal abduction or lateral abduction of the arm, the two rhomboids, rhomboideus major and rhomboideus minor, the levator scapulae and cranial fibers of the serratus anterior.

Asanas: –

See also: – 371: –

Other positions with the impact indicator 372

376 Stretching for depression of the shoulder blade:

Stretching that allows further depression of the scapula is far less common and usually far less necessary than stretching that allows further elevation. This is because the gravity of the arms pulls the shoulder blade in this direction in anatomically zero and many everyday postures and activities with the arms hanging down. Furthermore, unlike in the case of elevation, biarticular muscles do not restrict the movement. This stretching may be necessary if a person habitually holds their shoulder blades raised to some extent, which is not uncommon. In many cases, this may be due to psychological factors. If you want to improve your capacity for depression, all you need to do is hold a dumbbell of an appropriate weight in your hand with your arm hanging down.

Asanas: –

See also: – 370: –

Other attitudes with the impact indicator 376

377 Strengthening for depression of the shoulder blade:

In contrast to stretching in the direction of depression, strengthening in this direction is quite often necessary or useful. This strength is required, for example, when the body is moved relative to the arms, such as in upface dog, tolasana or pull-ups. Here, the indirect depressors such as the pectroralis major and the latissimus dorsi and the direct depressors of the shoulder blade such as the trapezius muscle can be used.

the shoulder blade such as the trapezius and pectoralis minor can work quite well from the respective position of the arm.

Asanas: –

See also: – 376: –

Other attitudes with the impact indicator 377

381 Stretch for external rotation of the shoulder blade:

The external rotation of the shoulder blade is a movement that is necessary to be able to lead the arm into wide frontal abduction or, with external rotation, into lateral abduction, whereby the limits of both movements are very similar or, in the case of maximum external rotation, identical. In order to exercise stretching in this direction, it therefore makes sense to exert force in the direction of an overhead position of the arm. The main external rotators of the scapula are the trapezius with its three parts and, to a lesser extent, the serratus anterior. The serratus anterior often has a noticeable tendency to spasm, especially in the pars descens when the shoulder blade is elevated against resistance, which is certainly partly due to increased basic tone caused by habitual factors in everyday postures, so that postures with further external rotation of the upper arm from the class of elbow postures ( elbow stand, right-angled elbow position, dog elbow position, shoulder opening at the chair) may be more favorable, as the greater external rotation of the upper arm further lateralizes the shoulder blade and thus shifts the sarcomere length of the trapezius into a slightly less short range.

Among the stretched muscles are mainly those retractors of the scapula that lift the external rotation: Latissimus dorsi (medial), levator scapulae, pectoralis minor, pectoralis major (medial), rhomboideus major and rhomboideus minor. However, some of these muscles can also be stretched well by protracting the scapula at only 90° abduction instead of in the overhead position of the arm, such as the levator scapulae and the rhomboids: Rhomboideus major and Rhomboideus minor.

Asanas: –

See also: – 412: –

Other positions with the impact indicator 381

382 Strengthening for external rotation of the shoulder blade:

External rotation of the scapula usually takes place with further lateral abduction or frontal abduction of the arm. However, it can also be performed independently of this. It is then somewhat reminiscent of trying to „flap your wings“. However, this is not easy to practise as any effort to move the slightly abducted arms outwards against resistance usually leads to the supraspinatus and deltoid muscles being used. However, if you abduct the arms a little and do not work against any resistance, the movement is easy to find. To strengthen the external rotation, it is advisable to abduct the arms laterally as a pure punctum mobile, i.e. to move the elbows overhead in a medial direction. If the arms were positioned as a punctum fixum, for example in a handstand, the extensor of the elbow joint, the triceps, would work on the movement in the event of significant flexibility restrictions when attempting to move the elbows towards each other and the effort would be kept at least partially away from the external rotators. Of course, this effect depends on the given flexibility and the distance between the hands.

Asanas: –

See also: – 412: –

Other positions with the impact indicator 382

386 Stretch for internal rotation of the shoulder blade:

Stretching in the direction of internal rotation, i.e. stretching the external rotators of the scapula, may be necessary if parts of the trapezius have too high a tone for habitual reasons and the scapula can therefore never return to full internal rotation. The muscles responsible for this are the levator scapulae and the rhomboids: Rhomboideus major and Rhomboideus minor. However, these are also elevators of the scapula. Complaints about a tense trapezius are common and can usually be traced back to everyday posture in which the shoulder blades are held slightly raised or the arms are held slightly raised and twisted for various activities. Postures and exercises that depress the shoulder blades are helpful in these cases. Many people find it difficult to distinguish between exerting force in the direction of lateral adduction and internal rotation. Therefore, postures that perform these movements together should be practiced. The most important internal rotators are the rhomboids, which are also retractors of the shoulder blade.

Asanas: –

See also: – 412: –

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 386

387 Strengthening for internal rotation of the shoulder blade:

Asanas: –

See also: – 412: –

Other attitudes with the impact indicator 387

390 Dyskinesia of the scapula:

Asanas: –

See also: – 412: –

Other positions with the impact indicator 390

411 Stretching for dorsiflexion in the wrist:

Here, the wrist palmar flexors together with the finger flex ors are boundary-setting. It is not uncommon for the finger flexors (usually the superficial flexors) to set the boundary a little earlier than the palmar flexors, which then becomes visible in the proximal finger joints lifting off the ground.

Asanas: – palmar forearm stretch – palmar forearm stretch in upavista konasana – upface dog – vasisthasana – ardha vasisthasana – handstand – right-angled handstand – parsakonasana – urdhva dhanurasana – purvottanasana with outstretched arms, both hand positions – three-point headstand

See also:

412: strengthening the dorsiflexors of the wrist

glossary: dorsiflexion of the hand

glossary: dorsiflexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand ( countermovement)

glossary: palmar flexors of the of the hand (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 411

412 Strengthening for dorsiflexion of the wrist:

Dorsiflexors are not significantly strengthened in yoga poses except to stabilize the wrist, e.g. the lower arm in trikonasana, when the upper body is rotated through arm strength, and in arm balances such as tolasana for balance work. The postures on fists also use the dorsiflexors to stabilize the wrist.

Asanas: – trikonasana – tolasana

See also:

glossary:- 412: Stretching the dorsiflexors of the wrist

glossary: dorsiflexion of the hand

glossary: dorsiflexors of the hand (agonists)

glossary: palmar flexion of the hand (countermovement)

glossary: palmar flexors of the hand (antagonists)

glossary: wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 412

416 Stretching for palmar flexion in the wrist:

The ability to flex the palmar flexion clearly depends on the condition of the fingers: in a flexed state, i.e. with a closed fist, the finger extensors place the greatest restriction on movement in the direction of palmar flexion. If the fingers are more or less extended or at least not actively flexed, the movement is only restricted by muscles that do not move the fingers, such as flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus. Accordingly, the dorsal forearm stretch is the most important posture for stretching; if the finger flexors are not to be stretched, the fist can simply be opened.

Asanas: – Dorsal unterarmdehnung

See also:

417: strengthening the palmar flexors of the wrist – –

Other attitudes with the impact indicator 416

417 Strengthening for palmar flexion in the wrist:

All postures that provide powerful support on the floor are relevant here, the more balancing character they have, the more so. Finger flexors and, secondarily, wrist palmar flexors are strengthened.

Asanas: – palmar forearm stretch strengthens lightly – palmar forearm stretch in upavista konasana strengthens lightly – upface dog – vasisthasana – ardha vasisthasana – handstand – right-angled handstand – urdhva dhanurasana with both hand positions – purvottanasana with outstretched arms, both hand positions

See also:

416: Stretching the palmar flexors of the wrist

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 417

421 Stretching the finger flexors:

For a good stretch of the finger flex ors, the fingers must be stretched as fully as possible plus a wide dorsiflexion of the wrist, as achieved in isolation by the functional exercises forearm stretch palmar and forearm stretch palmar in upavista konasana. A range of motion in the metacarpophalangeal joints that exceeds 180° would not be used to stretch the finger flexors for physiological reasons. Firstly, it is far too inconsistent between individuals, so that it is impossible to predict its effectiveness and side effects, and secondly, there is a risk of further loosening the ligament structure of the hand. If stretched finger joints(proximal and distal) and metacarpophalangeal joints are set, the stretching of the finger flexors can only be intensified by further dorsiflexion of the wrist. In doing so, 90° should be reached and, if possible, exceeded. In addition to the above poses, other suitable poses include those with the fingers extended and the wrist at an angle of around 90°, such as handstand, right-angled handstand, three-point headstand, ardha vasisthasana, tolasana, upward facing dog. Depending on shoulder flexibility (the lower the more), urdhva dhanurasana (back arch) can also work excellently, as the angle of dorsiflexion must exceed 90° if the shoulder joints are less mobile.

Asanas: – palmar forearm stretch – palmar forearm stetch in upavista konasana – handstand – rectangular handstand – three point headstand – ardha vasisthasana – tolasana – upface dog – urdhva dhanurasana (back arch)

Siehe auch:

422: strengthening der finger flexors

423: tonus of the finger flexors

glossary: fingerbeuger / fingerflexoren

glossary: finger extension / finger extensors (antagonists)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 421

422 Strengthening the finger flexors:

Finger flexors are mainly strengthened in variations with the fingertips up. Postures in which pulling movements are performed with flexed fingers are also suitable, such as the twisting pose or seated forward bends. Of course, the sarcomere length in which the finger flexors work is shorter in the latter, so that other postures are preferable in the event of increased tone, as otherwise a further increase in tone and a cramp can easily result.

Asanas: – downface dog on fing ertips – upface dog on fingertips – staff on fingertips – handstand on fingertips – right-angled handstand on fing ertips – vasisthasana on fingertips – ardha vasisthasana on fingertips – twisting pose – janu sirsasana – pascimottanasana – tryangamukhaikapada pascimottanasana – table-top variation of uttanasana – table-top variation of uttanasana – parivrtta variation of uttanasana – parivrtta trikonasana

See also:

421: Stretching the finger flexors

423: Tone of the finger flexors

glossary: finger flexors / finger flexors

glossary: finger extensors / finger extensors (antagonists)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 422

423 Tone of the finger flexors:

The tone of the finger flexors can be increased to such an extent that they are prone to cramp even with short-term strain. This occurs in particular when they work at a short sarcomere length, such as in a twisting position or in seated forward bends where the outer foot is pulled. Stretching these muscles naturally reduces tone, but in some cases postures in which the sarcomere length is moderate also have a positive effect. This includes all postures in which the fingers are extended and the wrist is in any position (including dorsiflexion).

Asanas: – forearm stretch palmar – forearm stretch palmar in upavista konasana – handstand – right-angled handstand – three-point headstand – vasisthasana – ardha vasisthasana – tolasana – upface dog – urdhva dhanurasana (bridge )

See also:

421: Stretching the finger flexors

422: Strengthening the finger flexors

glossary: finger flexors / finger flexors

glossary: finger extensors / finger extensors (antagonists)

Other attitudes with the impact indicator 423

426 Stretching the finger extensors:

Stretching the finger extensors requires the fingers to be flexed as fully as possible plus palmar flexion of the wrist. As there are no postures that support the body weight on the back of a closed fist, the functional exercise dorsal forearm stretch is particularly suitable. If the fist is sufficiently closed, the finger flexors are flexed significantly more than the dorsiflexors of the wrist, as opening the fist in the posture and the immediately resulting increased dorsiflexion ability of the wrist quickly shows. The finger extensors are the greatest limitation when the wrist is flexed palmarward with a closed fist.

Asanas: – Dorsal forearm stretch

See also:

427: strengthening the finger extensors

428: tone of the finger extensors

glossary: finger extensors / finger extensors

glossary: finger flexors / finger flexors (antagonists)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 426

427 Strengthening the finger extensors:

Strengthening the finger extensors is atypical for yoga poses. There are no poses that open a closed fist against resistance, nor are there poses that support the back of the hand and use the finger flexors to stabilize the angle in the wrist. Only a trikonasana, for example, in which the hand resting on the lower leg pushes forcefully backwards to move the corresponding shoulder forwards, can contribute a little to strengthening the finger extensors, depending on the grip technique.

Asanas:

See also:

426: Stretching the finger extensors

428: Tone of the finger extensors

glossary: finger extensors / finger extensors

glossary: finger flexors / finger flexors (antagonists)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 427

428 Tone of the finger extensors:

In addition to the stretching exercises listed above, postures with supporting fists and an extended wrist can also moderate excessive tone.

Asanas: – dog on top of fists – right-angled handstand on fists – handstand on fists

See also:

427: strengthening the finger extensors

426: stretching the finger extensors

glossary: finger extensors / finger extensors

glossary: finger flexors / finger flexors (antagonists)

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 428

501 Stretching the latissimus dorsi:

The latissimus dorsi is the most important and strongest adductor muscle in the shoulder joint and often restricts frontal abduction, which stretches the latissimus dorsi accordingly. The stretch benefits from the external rotation of the upper arm, as the latissimus dorsi is one of the internally rotating muscles due to its attachment to the humerus. In addition to the classic postures with 180°+ frontal abduction, postures with an inflected spine and a grip on the outer foot of an extended leg can also cause a stretch.

Asanas: – gomukhasana – hyperbola – raised back extension – downface dog wide – urdhva dhanurasana – handstand – right-angled handstand – elbow stand – right-angled elbow stand – dvi pada viparita dandasana – eka pada viparita dandasana – shoulder opening on the chair – janu sirsasana – parsva upavista konasana – parivrtta parsva upavista konasana – parivrtta janu sirsasana

See also:

427: strengthening the latissimus dorsi

glossary: latissismus dorsi

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

Further attitudes with the impact indicator 501

502 Strengthening the latissimus dorsi:

While pronounced strengthening of the latissimus dorsi is atypical for yoga poses, there are certainly opportunities to use strength for this muscle, such as seated or standing forward bends with pulling on one or both legs. Pressing the palms together in caturkonasana is also suitable for strengthening the latissimus dorsi, although not in the same way as pull-ups. A more exotic variation is parsvakonasana with a block in the hand, in which an appropriate dumbbell is held instead of a light block. This is also less of a pronounced strength training exercise and more of a strength endurance training exercise, especially as the muscular capacity of the latissimus dorsi in such a long sarcomere length as in parsvakonasanais rather low.

Asanas: – trikonasana (as lateral flexor and when using the lower arm for adduction) – uttanasana with traction on the lower legs – ardha chandrasana – janu sirsasana – parsva upavista konasana – caturkonasana – parsvakonasana with block in hand

See also:

426: stretching the latissimus dorsi

glossary: latissismus dorsi

glossary: lateral adduction in the shoulder joint

glossary: frontal adduction in the shoulder joint

Other positions with the impact indicator 502

511 Stretching of the pectoralis major: