yogabook / asanas / downface dog

Contents

- 1 adho mukha svanasana„downface dog“

- 2 Variants

- 2.1 wide

- 2.2 Hands on the wall

- 2.3 Feet on the wall

- 2.4 Raise one leg backwards and upwards (eka pada prasarita)

- 2.5 on fists

- 2.6 on fingertips

- 2.7 Press your hands more firmly on the floor

- 2.8 Push hands towards each other

- 2.9 Tighten your biceps

- 2.10 Head on the ground

- 2.11 Raise and lower wrists

- 2.12 one-handed

- 2.13 Heel on the ground

- 2.14 Knees bent

- 2.15 stretch from bent knees

- 2.16 Shrug

- 2.17 Chest to one leg

- 2.18 one leg bent

- 2.19 one leg stretched out in front (hip opener 5)

- 2.20 narrow

- 2.21 Hands turned out (ulnar abduction)

- 2.22 Hands turned in

- 2.23 eka pada parsva

- 2.24 from the outside hand to the inside hand

- 2.25 with upturned feet

- 2.26 Dips

- 2.27 Backwards against the wall with your leg raised

- 2.28 Hands on blocks

- 2.29 Heels on blocks

- 2.30 Hands on carpet / blanket

- 2.31 close with hands on the wall

- 2.32 (S) Partner exercise with 1 supporter

- 2.33 (S) Partner exercise with 2 supporters

- 2.34 (S) Partner exercise with 3 supporters

- 2.35 (S) Partner exercise with 4 supporters

- 2.36 (S) Pull on the thighs

- 2.37 (S) Shrug

- 2.38 (S) Shrugging with traction on the thighs

- 2.39 (S) Dips

- 2.40 (S) Turn out arms

- 2.41 (P) stretch from bent knees

- 2.42 (S) Pressure on the sacrum

- 2.43 (S) backwards against the wall with lifted leg: correct leg and pelvis

- 2.44 (P) backwards against the wall with lifted leg: pull on the outer groin

- 2.45 (P) backwards against the wall with lifted leg: turn out arms and press shoulder area

- 2.46 (2P) backwards against the wall with lifted leg: pull on the outer groin and correct the pelvis

- 2.47 (3P) backwards against the wall with lifted leg: pull on the outer groin, correct pelvis, press shoulder area

- 2.48 Transition to supta virasana

- 2.49 Detail photos

- 2.50 Transition to uttanasana

- 2.51 Transition to ardha vasisthasana and back

- 2.52 Transition to upface dog

- 2.53 Transition to upface dog with feet stretched out

- 2.54 Transition to parsvakonasana

- 2.55 Transition to staff pose

- 2.56 Transition to dog elbow stand

- 2.57 Transition to upface dog against own shoulder strength

- 2.58 (P) Transition to upface dog against resistance

- 2.59 Transition to uttanasana to the back

- 2.60 Transition to handstand, one-legged

- 2.61 Transition to handstand, two-legged

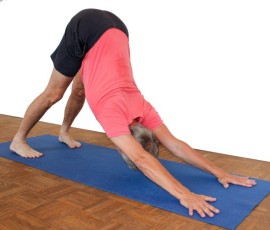

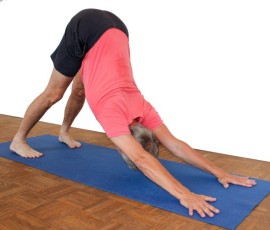

adho mukha svanasana

„downface dog“

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

Do and don’t

Turn in the arms, retract the shoulderblades | turn out the arms, lateralize the shoulder blades |

Feedback: We’d love to hear what you think about this description, give us feedback at:

postmeister@yogabook.org

last update: 30.12.2018

Name: adho mukha svanasana

Trivial name: downface dog / dog pose with the head down

Level: A

- Classification

- Contraindication

- Effects

- Preparation

- Follow-up

- derived asanas

- similar asanas

- Diagnostics

- Instructions

- Details

- Variants

Classification

classical:

psychomental: balancing, mood-lifting

physiological: hip flexion (therefore stretching the hamstrings), spine extension, shoulder opening (frontal abduction), forearm strengthening

Contraindication

In cases of acute intervertebral disc disease, the area of the lumbar spine can take a convex curvature in cases of a less flexible hamstrings, which causes or maintains the known pain/radiation of pain.

Effects

- (232) Force for frontal abduction

- (292) Strengthening the trapezius

only pars descendens - (332) Force for pronation of the forearm

- (232) Force for frontal abduction

with less mobile shoulders - (231) Shoulder joint: stretching for frontal abduction

- (321) Stretching the supinators of the forearm

- (721) Elongation of the hamstrings

- (851) Stretching the calf muscles

- (851) Elongation of the gastrocnemius

Preparation

An important preparation for all those who are not particularly flexible in the hamstrings is to warm them up so that hip flexion is easier in this position and the upper body moves more easily towards the thighs:

- uttanasana as a generally effective and efficient stretch of the hamstrings to prepare for flexion in the hip joints in this pose, so that insufficient flexion does not restrict the work in the shoulders

- prasarita padottanasana

- hip opener 5 as a very effective stretch of the hamstrings that goes beyond uttanasana

- warrior 3 pose due to flexion in the hip joint of the standing leg

- parsvottanasana as a very effective and efficient stretch of the hamstrings with additional significant stretching of the gastrocnemius

- parivrtta trikonasana is also a good stretch of the hamstrings with additional significant stretching of the gastrocnemius.

- uttanasana as a generally effective and efficient stretch of the hamstrings to prepare for flexion in the hip joints

Depending on the flexibility and resilience of the shoulder, it is advisable to warm it up well too:

- upface dog as a pose that prepares the shoulders for powerful work, especially through correctly executed transitions from and to downface dog

- rectangular handstand

- back stretching, especially the „elevated“ version as a general stretch of the shoulder and hamstrings

- dog elbow stand

- hyperbola as one of the most effective and efficient stretches in the direction of frontal abduction without external rotation of the arms

- Shoulder opening on the chair as one of the most effective and efficient stretches in the direction of frontal abduction with external rotation of the arms

- purvottanasana if the tone in the deltoid is too high or has become too high due to preparation

- gomukhasana if the tone in the deltoid is too high or has become too high due to preparation

The following poses can be used to prepare the calf muscles, especially the gastrocnemius, for dorsal flexion in the ankle:

- warrior 1 pose in which the respective rear leg is stretched

- parivrtta trikonasana in which the respective back leg is stretched

- parsvottanasana in which the respective back leg is stretched

- uttanasana with the ball of the foot on a block

- downface dog with one leg raised

- downface dog with one foot hooked behind the opposite knee

To counteract an existing tendency to cramp in the rectus femoris:

- supta virasana

- ardha supta krouncasana

- quadriceps stretch 1 on the wall

- quadriceps stretch 2 on the wall

Follow-up

If unpleasant tension remains in the deltoid after leaving the dog position, this can be reduced with:

- gomukhasana in which the deltoid of the lower arm is stretched

- uttanasana with hands behind the body for both arms simultaneously

- prasarita padottanasana for both arms simultaneously

If the rectus femoris has shown a tendency to cramp in the dog:

Derived asanas:

Similar asanas:

Geometry:

- rectangular handstand

- urdhva hastasana-variant of the dandasana

- supta dandasana

- rectangular uttanasana

- rectangular headstand

- navasana

- dvi-pada variant of handstand

Diagnostics (No.)

(712) Hip flexor: strength

A lack of strength in the hip flexors in this pose will mean that the attempt to tilt the pelvis into wide flexion in the hip joints will not result in any significant stretching of the hamstrings.

(293) Excessive tension in the trapezius:

It is rather rare for the trapezius to tense up despite stretching from the shoulder (elevation) and turning out (external rotation) of the arms, which then indicates significantly increased tension. The trapezius, which plays a key role in lifting and outwardly rotating the shoulder blades, is probably one of the most tense muscles in Western civilization. Internal and external posture, including today’s widespread VDU workstations, contribute significantly to this.

(880) Hyperextension of the knee:

Hyperextension of the knee joints refers to the ability to or the current state of an angle of more than 180° in the knee joint. To a certain extent, this is considered normal by anatomists and is on average more common and more pronounced in females. However, it can also indicate weakness of the quadriceps or hamstrings. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for unphysiological sensations to occur in the front of the knee below the patella or on the back of the knee during hyperextension, which are not caused by stretching or straining the muscles and should be avoided, see also FAQ.

In downface dog, the flexibility of the shoulder joints can be recognized, including side discrepancies, and there may be indications of diseases of the shoulder joint:

- Irritable hypertonus of the deltoid: especially ambitious beginners in yoga tend to develop irritation in the deltoid, which is localized in the area of the muscle origins, presumably due to an overstraining of the structures by frequently repeated demand in full frontal abduction and is also noticeable in such stress, see FAQ.

- Various pathological changes of the shoulder joint such as impingement syndrome, frozen shoulder, calcifications of the biceps tendon, which cannot all be discussed here and require clarification.

- side discrepancies in flexibility

The flexibility of the shoulder joint is recognizable in the form of the degree of evasion in the three dimensions of movement:

- Moving the upper arms outwards (laterally) with (as the hands are fixed) consecutive bending of the elbow joints, as the hands are fixed

- Loss of external rotation of the arms

- An angle of frontal abduction that does not reach 180° or not permanently

(650) Kyphosis and lordosis of the spine:

The deviations from the physiological double-S shape of the human spine are clearly visible in this pose. There should be a certain degree of lordosis (convex spine from the front) in the cervical spine and no kyphosis (convex spine from the back) in the thoracic spine. The physiological kyphosis should also be eliminated and this area of the back should be able to be fully extended. The extent to which the physiological lordosis of the lumbar spine can be restored is extremely dependent on the flexibility of the hamstrings and the focus of the pose. Depending on the focus of the pose, even flexible people may still have a „merely“ straight or slightly kyphotic lumbar spine. The decisive parameters here are above all the distance between the hands and the feet and the question of whether the heels are pressed to the floor at the expense of flexion in the hip joints. See the FAQ.

(611) Pelvic obliquity / scoliosis of the spine:

The lateral deviations of the spine from the sagittal plane known as scoliosis are also quite visible in this pose. It is also sometimes observed that the pelvis is not straight, but that one hip is higher than the other, which may also be due to different flexibility of the gastrocnemius (side comparision). See the FAQ.

Various disorders can be found in forward bending movements (flexion in the hip joints), but also under load in the muscles of the back of the leg:

- Shortening of the hamstrings, see FAQ.

- Damage to the hamstrings that causes pain or functional limitations can also be easily recognized here, from simple tension to strains to muscle (partial) tears. Tears can lead to greater unilateral flexibility in the direction of dorsiflexion in the ankle joint.

- Irritation of the ischiadicus nerve which innervates the leg and foot, can become symptomatic during forward bends in particular, even if they are otherwise rather calm. See the FAQ.

- Irritation of the origin of the hamstrings at the ischial tuberosity (also called PHT: Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy) can become clearly evident in this pose, depending on the force with which the pelvis is tilted, and requires protection from intensive stretching, as required by this pose. See the FAQ.

- Baker’s cysts create a feeling of tension or a foreign body sensation in the back of the knee, see FAQ.

Although the wrist is far less in dorsiflexion than, for example, in upface dogwards, one or the other disturbance in the hand or wrist can still come to light under about a quarter of the body weight.

- Ganglion, usually in the dorsal area between the hand and forearm, produces a sensation of pressure when the wrist is flexed dorsally, if more pronounced. This occurs much less frequently in downface dog compared to the upface dog and usually only in the combination of a less mobile hamstrings and a less flexible shoulder joint.

- Tendinitis of the tendons of the palmar flexors or especially the finger flexors

- Carpal tunnel syndrome: worsening of symptoms in this pose, especially when the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers are pressed hard against the floor

- Fractures and fractures of carpal bones, especially the scaphoid bone

- Arthritic change in the joint

- Arthritis (inflammation of the joints) of various kinds

- Dislocation / subluxation, not only of the wrist (radiocarpal joint), but also misalignment of carpal bones, which would usually cause a significantly increased sensation of tension in various muscles covering the wrist.

- joint trauma, which may cause pain in the joint even after many weeks or months

but also mainly muscular symptoms such as:

- Golfer’s elbow: Strain pain at the point of origin of the muscles of the inner ulnar side of the forearm in the transition to the upper arm. See FAQ.

In this position, knee problems associated with stretching the knee joint under a certain load can become apparent. These can be, for example: traumatic or degenerative meniscus damage, arthrosis, arthritis, subluxations, ligament damage, plica syndromes, Hoffa syndromes (of the extended leg), retropatellar cartilage damage (chondropathia patellae, retropatellar arthrosis/osteoarthritis) and others, see the FAQ.

Variants:

Raise one leg backwards and upwards (eka pada prasarita)

Press your hands more firmly on the floor

one leg stretched out in front (hip opener 5)

Hands turned out (ulnar abduction)

from the outside hand to the inside hand

Backwards against the wall with your leg raised

(S) Partner exercise with 1 supporter

(S) Partner exercise with 2 supporters

(S) Partner exercise with 3 supporters

(S) Partner exercise with 4 supporters

Backwards against the wall with your leg lifted: correct your leg and pelvis

Backwards against the wall with your leg raised: pull on the outer rail

Backwards against the wall with your leg raised: pull on the outer rail

Backwards against the wall with your leg raised: pull on the outer rail

Backwards against the wall with your leg raised: pull on the outer rail

Transition to ardha vasisthasana and back

Transition to dog position head up

Transition to dog on top with feet stretched out

Transition to upface dog against own shoulder strength

(S) Transition to upface dog against resistance

Transition to uttanasana to the back

Transition to handstand, one-legged

Transition to handstand, two-legged

Instructions

- Sit upright on the lower legs of both feet.

- Bend your upper body forward and down and rest it on your thighs.

- Stretch your arms out in front of you and press your open palms shoulder-width apart on the floor.

- Raise your pelvis until your thighs are vertical.

- Turn your toes over so that the bottoms of your toes are on the floor.

- Put weight on your hands.

- Stretch your legs backwards and push your upper body towards your legs.

- Lower your heels.

- Tilt the pelvis forward and down to the maximum tolerable level of stretching sensation in the hamstrings.

- Let the shoulder sink into the line connecting the wrists and ischial tuberosities, but do not move it forwards and downwards towards the hands but upwards and backwards towards the pelvis.

- Press the inner base joints (metacarpophalangeal joint) of each finger (joints between fingers and palm) firmly onto the floor to distribute the pressure between the different parts of the hand and fingers as evenly as possible.

- Turn the upper arms out (i.e. the triceps towards the floor).

- Stretch from the shoulders backwards and upwards to the maximum, i.e. elevate the shoulder blades to the maximum.

Details

- Pay attention to the leg work: exact extension of the knee joints, unless the rectus femoris of the thigh would cramp (because it is short in both joints that it spans (knee joint and hip joint), and therefore very short in sarcomere length, close to active and passive insufficiency, hence prone to cramp). If a cramp occurs, then:

- If necessary, do not tilt the pelvis quite so far in downface dog.

- Practise stretching the quadriceps more frequently, e.g. supta virasana, quadriceps stretch 1, quadriceps stretch 2, ardha supta krouncasana.

- Bend the knee joints first and then tilt the pelvis further forwards and downwards instead of stretching the legs first and then tilting the pelvis into hip flexion, as is usual. Flexion in the hip joints should be performed mostly isolated by the iliopsoas and, as far as possible, not from the rectus femoris.

- Using the strength of the arms and shoulders, push the ischial tuberosities away from the hands, which means nothing other than stretching all the joints in between to the maximum including elevating the shoulder blades, see below.

- Leave the abdominal muscles soft. The shoulder area should not be moved towards the legs by means of the rectus abdominis, but by an adequately tilted pelvis (flexion in the hips), i.e. by the strength of the hip flexors.

- If there is a tendency to cramp in the shoulder muscles (deltoids), this can be avoided:

- if this significantly restricts the execution of the exercise, the downface dog with the hands on the wall can be practiced more often instead. Furthermore

- in between, or if the tendency to cramp hinders the execution of the pose too much, (half) gomukhasana can be practiced. If handstand with bent arms (dips variation) can be practiced, this is also highly recommended.

- Switch to the upface dog more often in between.

- Tonus-regulating strengthening exercises and strengthening of various kinds should be practiced, including the dips variation of dog pose.

- Turn the thighs in rather than out (which is not part of the pose anyway) and push them away from each other, this pulls the ischial tuberosities apart a little and promotes flexion in the hip joints a little.

- In some cases, the weight distribution between the inner and outer foot requires special attention. In cases of shortened calf muscles in particular, it can be useful to focus more often on pushing down on the inner heel. This is the case, for example, for athletes who regularly subject their lower leg muscles to greater strain, e.g. by jogging, endurance running or similar, as the gastrocnemius trained in this way also supinates the foot.

- Make sure that the inner hands do not become light when turning the arms out, but work constantly with the forearm muscles, esp. the palmar flexors and pronators, as pushing down the inner finger base joints, which tend to lift, is a combination of palmar flexion in the wrist and pronation of the hand or forearm. Nevertheless turn out your arms to the maximum.

- Difficulties with the wrists (usually dorsal) can occur after holding the position for a long time, especially if the hamstrings are not very flexible and the shoulder joints are not very flexible, and are almost invariably of a temporary nature. This can be remedied:

- in the pose: the more forceful pressing down of the m metacarpophalangeal joints

- after the pose: stretching the dorsiflexors and finger extensors

- When stretching from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) backwards and upwards, make sure that the external rotation of the arms is not lost. The well-known relationship between the three dimensions of movement (turn out, don’t laterally adduct, maximum frontally abduct) naturally applies here all the more. The force acting in the direction of frontal abduction is great enough to force the upper arm in the shoulder joint into the other two dimensions of movement in case of doubt, depending on which movement is easier or, conversely, which can be better controlled by awareness and strength. So be very careful not to let the arms deviate outwards and, even more importantly, not to let them rotate internally. People with instable shoulder joints in particular, especially those with a known tendency to shoulder dislocation/luxation, must carefully and maximally turn out their arms in any overhead movement, otherwise they may dislocate/luxate.

- Work with your hands in such a way that individual or several fingers do not turn sideways, which can be easily recognized, for example, by a nail leaning to the side. If this is the case, a sideways sliding movement of the whole hand or individual fingers can be used to bring the fingers into an upright position (against the frictional resistance of the fingers on the surface). This effect often does not affect all fingers equally. The specified correction is therefore only intended as a corrective for the unwilling fingers and accepts that the tendency of other fingers to rotate may be overcompensated in the meantime or that some fingers may even be rolled in the opposite direction. The degree of correction is based on the finger that rotates the most. Note that there is only two-dimensional mobility in the metacarpophalangeal joints: Abduction/adduction and flexion/extension, but not rotation. Any rotation of the finger is therefore not physiological and is limited by ligamentous structures that must not be loaded. This instruction naturally also applies to the thumb, although for anatomical reasons it cannot be expected to lie upright.

- There should be no tendency to cramp in the trapezius; if there is, you should first check whether this can be stopped by turning out the arms more forcefully yourself. If not, a supporter can turn out the arms with appropriate force. The causes of trapezius cramps are often habitual and can mostly be found in everyday postural behavior.

- As in various standing postures, spread the toes to create the basis for the metatarsophalangeal joints to rest on the floor as evenly as possible, as far as the transverse arch of the foot and its arched shape allow.

- In most cases, lowering or pushing down the heels counteracts flexion in the hip joints, as both movements are coupled via the limited flexibility of the muscles in the back of the leg. The gastrocnemius plays an important role here, as this plantar flexor of the ankle simultaneously flexes the knee joint. In downface dog, the opposite movement is undertaken in both joints, so that it is strongly stretched here and usually sets the limit in at least one of the two movements (flexion in the hip joints and plantar flexion). Unless otherwise indicated (therapeutically, e.g. for PHT), the movement in the hip joints is the more important one, i.e. place more emphasis on tilting the pelvis as far as possible than forcing the heels to the floor; however, this makes perfect sense as a temporary focus of the exercise. This is especially true if the gastrocnemius is quite stiff. Downface dog can then also be used to promote its flexiblity. After all, its shortening is a significant risk factor for some disorders in the kinetic chain of the lower limb. However, variations in which only one foot is on the floor are particularly suitable, such as the eka pada prasarita variation or the variation with one leg bent, the foot of which can also be hooked behind the opposite knee.

- The above instructions for taking the pose provide a clear measurement for the distance between hands and feet. If you change from downface dog to upface dog, the distance between hands and feet must be adjusted accordingly so that the wrists are no further forward – preferably one or two centimeters backward – than the perpendicular of the shoulders. If you switch between these two poses several times, the distance should be measured according to this criterion for upface dog and should not be changed each time you switch. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule, such as disc herniations, which require such a large distance in downface dog that the lumbar spine is at worst steeply positioned (if this is tolerable), but upface dog position must not be performed with a greater distance, so that regular changes between the distances must be made. For downface dog, this rule has the consequence that the pelvis tilts less or at least less easily forwards and downwards (flexion in the hip joints), but this is the lesser evil compared to too great a distance in the upface dog, which can lead to a nasty sag in the lower back. The advantages of the smaller distance for upface dog are described there, including the fact that the transitions are more intense and the deltoids are challenged more.

- In some people, the tendons of one or more fingers are shortened, usually the little finger. This peculiarity only affects the execution of the pose to the extent that the first finger joint cannot usually be pressed to the floor. If an assistant is available, they can usually continue to slowly press the affected joint down over the course of several minutes, which should be painless. Otherwise, a weight can be placed on the joint. Rapid success is not to be expected, especially if it is a tendon contracture, but a slow, steady improvement can be expected.

- If the palmar flexion is performed vigorously, the work of the associated muscles of the forearm should be clearly noticeable. In rare cases, this type of muscular work causes irritation at the origin of the muscles in the forearm near the elbow joint, such as golfer’s elbow, or an existing golfer’s elbow becomes more obvious. In this case, it is recommended that this work in downface dog be less forced and that the stretching of this muscle group be practiced more often with the palms of the hands placed on the floor. Therapeutic weight training with many repetitions with such a light weight that no pain occurs during the exercise is usually helpful. See also golfer’s elbow in pathology.

- A lack of strength in the forearm muscles in particular often puts a lot of uncomfortable pressure on the carpus. Less trained people often not only have little musculature to relieve pressure in this area, but also little protective musculature over the bones. Patches or shoulder stand plates with patches on top of them (for better friction) are recommended as softness mediators.

- Due to the unsupported heels and the possible longer time you can stand in downface dog, this pose is suitable for counteracting overtension in the longitudinal intrinsic foot muscles. As an active part of the tension belt of the foot, it is increased in quite a lot of people as a result of the demands placed on the feet, for example through prolonged standing or walking as well as various sporting activities.

- Sometimes an intense pressure sensation occurs at the hamulus, which makes it necessary to protect this area, e.g. by placing the rest of the hand on a support, but avoiding the hamulus.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Pain in the shoulder

Beginners who regularly or even ambitiously practise downface dog may develop a slight cramp-like pain in the ventral shoulder, which almost only occurs when the arms are overhead under at least a moderate load. This may also apply to handstand and rectangular handstand, for example, and is a result of the disproportion between the demand and the current capabilities of the muscles. It then makes sense to train the shoulder muscles (especially the frontal ones: the pars clavicularis of the deltoid) for strength and strength endurance in more moderate angles than approx. 180° frontal abduction. The dip variations of the poses with otherwise 180° frontal abduction are ideal for this, but above all the clean and intensively performed transition between downface dog and upface dog and back as well as front raises in a seated and supine position. See also the FAQ.

Variants

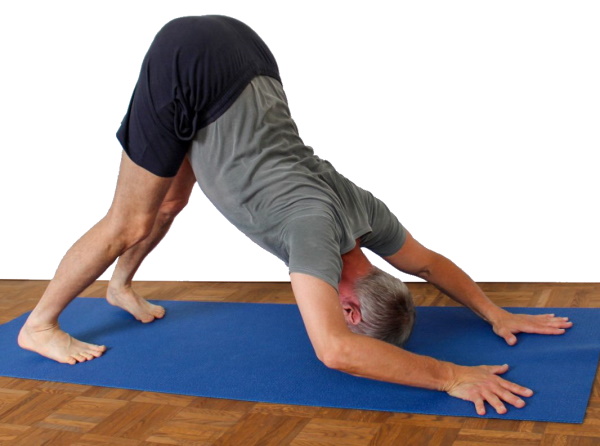

wide

This version allows a significantly improved „shoulder opening“ (promotion of frontal abduction capability) through the dog position as well as more powerful work in the lateral back muscles, which are stretched more intensively as adductors of the shoulder joint due to the greater force exerted here in the direction of frontal abduction.

Effects:

(231) Shoulder joint: stretching for frontal abduction

(501) Stretching the latissimus dorsi

Instructions

- Increase the distance between your hands and feet by at least one hand length, or up to two hand lengths (including fingers) if you are stiff in the shoulder joints.

- Stretch your body backwards even more forcefully. If you slip away with your hands, press them against the wall:

Details

- For people who are flexible in the shoulder joints, it is essential to ensure that they do not go into maximum frontal abduction of the shoulder joint if no stretch can be felt in the adductors of the shoulder joint. The less the body is stretched backwards away from the wrists (which anatomically corresponds to the elevation of the shoulder blades), the earlier this state is reached, as the latissimus dorsi, as an important shoulder joint adductor, is also an indirect depressor of the shoulder blade due to its attachment to the upper arm.

- This does not mean that the shoulder must not sink below the line connecting the pelvis to the hands, but rather that the extension of the body backwards must be maintained and developed through the strength of the shoulder blade elevators. If no stretch is felt in the shoulder joint adductors despite powerful and maximum elevation of the shoulder blades and maximum frontal abduction, you should switch to a variation in which the shoulder joint adductors are actively made to work instead of just being stretched, e.g. pressing hands on the floor or hands on carpet.

- As shoulder flexibility increases, you need to work more intensively to turn out the arms, which includes stretching the latissimus dorsi and the teres major, as these muscles are not only adductors but also internal rotators of the shoulder joint.

- For people who are stiff in the shoulder joint, the main task is to move the shoulders backwards (towards the feet) and upwards (towards the pelvis). Restricted flexibility of the shoulder joint limits both external rotation and frontal abduction as well as elevation of the shoulder blades.

- What was said above in the basic pose about the relationship between the three dimensions of movement (turning out, don’t move laterally, maximally frontally abduct) applies all the more here. The force acting in the direction of frontal abduction is great enough to force the shoulder joints into the other two dimensions of movement in case of doubt, depending on which movement is easier and which can be better controlled by awareness and strength. So be very careful not to let the arms deviate outwards and even more so not to let them turn in.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Slipping of the hands

As described above, hands can slip on the mat. This depends on the one hand on the typeof mat and how worn down it is, and on the other hand significantly on hand moisture. We always have some older patches (small pieces of mat) available in the yoga school to provide good reiction and slip resistance for participants who come with their own, less slip-resistant mat. Nevertheless, high hand moisture after intensive physical work or hyperhidrosis can cause the hands to slip. Placing your hands on a wooden floor is worth a try. If they are not too dry, the friction in a certain moisture range can be almost better than on a mat. Finally, as shown above, pushing the hands against a wall or gripping the edge of the mat, or having a supporter press the hands on the floor, can also help.

Hands on the wall

This version can reduce the tendency to cramp in the shoulder muscles (anterior parts of the deltoids) and help to turn out the arms. You may also be able to exert more force to push the upper body towards the thighs.

Instructions

- Press your hands against a wall so that your thumbs are pointing inwards and the rest of your fingers are pointing outwards, i.e. your index finger and thumb are in contact with the wall.

- Maintain the pressure, especially in the metacarpophalangeal joints, while holding the pose.

- Turn out your arms to the maximum while at the same time stretching backwards from the shoulder to the maximum, i.e. elevating the shoulder blades and finding the stretch in the latissimus dorsi that this allows.

Details

- Make sure that the metacarpophalangeal joints (especially the inner ones) do not lift but press firmly against the floor. This is the work of the palmar flexors and pronators in the forearm.

- This makes it easier to practise turning out the arms so that a certain intensity of stretching of the lateral back muscles (latissimus dorsi) can be experienced at the earliest possible stage.

- It should be noticeable that this variant reduces the tendency to cramp in the deltoids, if this exists.

- It is usually easier to push the upper body towards the thighs. This may be due to the fact that the strength for this is not limited by the fact that care must be taken to ensure that the hands do not slip forward, but it may also be due to the fact that in order to avoid this slipping away, the hands are often pressed onto the mat a little down from above in the normal version, which is equivalent to a frontal adduction movement (not exactly vectorial, but in the main direction for flexible people), which is diametrically opposed to the downward shoulder movement to be performed in downface dog, the frontal abduction. On the contrary, you may attempt to, subjectively, lift the hands upwards towards the front, which is equivalent to a further frontal abduction and at the same time pushes the shoulders and upper body towards the thighs.

- The stretch of the hamstrings should no longer be significant in this variant – which is not the aim of this variant – at best the calves are still noticeable in some cases.

Feet on the wall

This design allows:

- to shift the work a little away from the legs to the arms and shoulders

- to tilt the pelvis better forwards and downwards (flexion in the hip joints) and thus keep the back (especially the lower back) straighter (useful for some lower back injuries, especially disc herniations)

- to shift the work within the backs of the legs: away from the gastrocnemius towards the backs of the thighs (hamstrings).

Instructions

- Place your heels about 10-15 cm higher against the wall (depending on your flexibility in terms of dorsiflexion in the ankle joint: the better, the less height you need), place the balls of your feet on the floor in front of them so that your feet are at an angle of about 60° to the floor and take downface dog.

Details

- Make full use of the enlarged degree of freedom in the hip joints and tilt forwards and downwards into maximum flexion, defined by the maximum tolerable stretching sensation in the backs of the legs.

- Leave the lower back and the rectus femoris soft, i.e. get the movement from the strength of the iliopsoas. The pelvis may tilt much further here than usual and it becomes clearer where this movement comes from, as in the normal version there is no choice to change the position of the pelvis, especially for beginners with little flexibility, because the stiff back of the leg forces a certain position. This pose also shows the connection between the dorsal lower leg and dorsal thigh muscles: there is at least one knee flexor in both parts of the limb (thigh: hamstrings – lower leg: gastrocnemius) and depending on how far the pelvis is tilted, the heels can sink less towards the floor or vice versa, depending on how far the heels are moved towards the floor, the pelvis can be tilted less into flexion in the hip joints. If you want to put it this way, the total length of the back leg muscles is limited and you can choose between more flexion in the hip joints and more dorsal flexion in the ankles.

- Here, the strength of the arms can often be used better than in the normal pose to push the upper body towards the thighs, i.e. it is easier to push the shoulders below the line connecting the wrists to the pelvis, which primarily exercises the flexibility of the shoulders. This is because the pelvis tilts further and the upper body and therefore the shoulders can move further towards the thighs, which means that the force exerted with the hands in the direction of the shoulders forces the shoulders and upper body to move downwards rather than upwards. A comparable avoidance calculation can be found in the intensive transition between upface dog and head down without the use of force from the hip flexors in the instruction „lift the pelvis until the hip joints are above the line connecting the heels to the shoulders“ so that the pelvis deflects (is forced fo evade) upwards instead of downwards.

Raise one leg backwards and upwards (eka pada prasarita)

This pose strengthens the gluteus maximus and the biarticular hamstrings and increases the stretching and strengthening of the calf muscles (especially the gastrocnemius).

Effects:

(851) Stretching of the gastrocnemius

Instructions

- From the normal dog position, press your hands down firmly on the floor.

- Slowly lift one leg. Keep it stretched; lift it slowly to the maximum, whereby the work of the gluteus maximus of the lifted leg (free leg) and the stretching and strengthening demands on the gastrocnemius of the standing leg should be clearly noticeable.

Details

- Feel the quadriceps of the lifted leg working. If you cannot feel it, there is usually no full extension in the knee, after all, the hamstrings are heavily involved in lifting the leg and inevitably generate a significant flexion moment in the knee joint.

- Stop the tendency of the lifted leg to turn out. Instead, concentrate on moving the inner knee upwards first.

- The further the leg is lifted, the more stretching sensation occurs in the standing leg; lifting the leg wide promotes flexion in the hip joint of the standing leg.

- Also make sure that the pelvis remains straight. The hip of the leg to be lifted wants to move forwards and upwards, which is perceived as a reduction in stretching sensation in the standing leg.

- In the lifted leg, stretch the heel forwards backwards and upwards, which eases straightening the knee joint. Do not work with the intention of lifting the heel or the calf, but rather the back of the thigh and, in particular, the inside of the thigh using the strength of the back of the leg itself and the gluteus maximus muscle.

- If the heel of the standing leg does not touch the ground, you will feel a significantly increased stretching requirement in the gastrocnemius, which may be borderline or even too strong. In the latter case, the heel can remain slightly raised or a small support can be used under the heel. If the heel of the same leg rests firmly on the floor, the stretching requirement will probably not be significantly increased as long as the lifted leg does not clearly tilt the pelvis further into flexion. If this occurs, however, the stretching of the gastrocnemius will also be clearly noticeable in most cases. If there is still no adequate stretching, increase the distance between the hands and the foot. In this pose the physical base of support is a very narrow triangle at the back; this means that the rein system of the ankle joint of the standing leg has to perform a certain amount of balancing work, which should be clearly felt as work of these muscles beyond any stretching sensation occuring. The balance aspect of the pose is reinforced by the fact that the rear foot is not positioned in a straight line behind the center of gravity plumb line, or in other words, the gravity perpendicular is not centered in relation to the transverse axis of the physical support base.

on fists

This version sometimes makes it possible to perform downface dog if various injuries to the wrist or the hand itself would otherwise prevent it, e.g. in the case of a scaphoid fracture.

Instructions

- Clench your hands into a fist and place your fists so that your palms are facing each other. The thumbs enclose the fist from the outside.

- Press your fists firmly on the floor and take downface dog as usual.

Details

- In this version, less pressure can be applied backwards, as the knuckles are typically more sensitive to pressure than the palms, and also because the wrist is often working at the limit of available ulnar abduction and therefore does not want to tilt further due to painful restriction of movement .

- Do not experiment with hands turned backwards (palms facing backwards), as the wrist is very unstable and there is a risk of injury from twisting the wrist.

- Apply pressure as evenly as possible to all knuckles pressing on the floor.

- The further the shoulders are moved backwards (and therefore down), the greater the ulnar abduction of the wrist, which is quite an unusual movement, especially when force is applied, and may also be less pronounced than would be required according to the flexibility of the shoulder joints and the hamstrings.

- If the pressure is very uncomfortable, patches can be used under the knuckles. A blanket would be inappropriate as an aid, as both the fists tend to slip on the blanket and the different layers of a folded blanket tend to slide against each other. For the latter reason, the otherwise promising combination of blanket and patches on top is also not a good choice. This is simply due to the often flat angle of the force applied via the forearms to the floor, and becomes more pronounced with increasing flexibility of the shoulder joints and the hamstrings.

- Not only is less strength available for stretching from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) as described above, the „shoulder opening“ effect (promoting frontal abduction capability) also suffers a little in this variation, as the intensive palmar flexion that is usually performed pushes the shoulders a little towards the floor and therefore stretches them better. In addition, discomfort in the wrists may prevent maximum frontal abduction of the shoulder joints.

on fingertips

This version strengthens the fingers, especially the profound and superficial finger flexors. The transition to upface dog on fingertips, is very interesting from a psychomental point of view, as confidence, freedom from fear and steadfastness during (increasing) stress are practiced here. In any case, decisiveness and clarity are also required and encouraged.

Effects:

(422) Strength of the finger flexors

Instructions

- With your knees still on the floor, place your fingertips on the floor slightly turned outward compared to normal dog position.

- Press your fingers firmly onto the floor and push them towards your thumbs against the friction of the mat using the flexors of your fingers. Be aware that your fingers will carry you.

- As you stretch your knees, apply more and more pressure to your fingers until you have fully taken the position.

Details

- To make it easier, the hand can be turned out a little more (thumb inwards).

- This requires determination and confidence. I only saw very few people who have such weak fingers that they would not be able to perform this pose. For almost all people, the task lies more in overcoming and trusting. The latter applies all the more to the positions upface dog on fingertips and staff pose on fingertips, whereby these two variations actually require considerable strength in the fingers, which perhaps not everyone can muster.

- In this position, there is a lot of pressure in the finger joints, which causes them to hyperextend (or, in rare cases, bend strongly). Make sure that the fingers overstretch as little as possible (i.e. the finger joints should become as little concave when viewed from the back of the hand as possible). To do this, take the pose with a clear pretension in the fingers, i.e. use the strength of the finger flexor muscles to push the fingers together and towards the thumb against the resistance of the floor. This reduces the tendency of the fingers to hyperextend when performed with sufficient force. Executions with convex (bent) finger joints are not advisable as the position of the joints is much more difficult to control. A certain degree of hyperextension as the starting position is normal and tolerable, as the finger flexors, which are used most forcefully, try to bring the joints out of or minimise their hyperextension. In contrast to the finger extensors, the finger flexors in humans are much stronger, which is why it is highly likely that the harmful forces in the joint that would be caused by uncontrolled hyperextension under load are largely absorbed during this attempt.

- Executions with the inner metacarpophalangeal joints on the floor are not permitted, as weight has a destructive effect on these joints by wearing out the ligament structure (or even acting on the cartilage of the joint surfaces) and the desired strengthening of the fingers is not achieved. Instead, position the fingers quite steeply.

- It can be said that, as a rule, execution is possible if you know that it is, or if you are undoubtedly determined to do so. Very rare exceptions may confirm this rule.

- If you feel that the skin is being pulled away from under your fingernails, move your fingers closer together and towards your thumb to compensate for the forces causing this sensation.

- Of course, a few aspects of the normal dog pose remain underrepresented here, such as the powerful stretching from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) and the pressure with which more flexible people can push the upper body towards the thighs.

Press your hands more firmly on the floor

This is completely different work in dog pose. Instead of pushing the body backwards from the hands, emphasis is placed on pushing the hands down. This tends to pull the hands and feet towards each other, which involves strong work of the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis), the iliopsoas, some leg muscles, the pectoralis major and possibly the latissimus dorsi.

Instructions

- From normal downface dog give up the pressure of the body backwards.

- Begin to press your hands onto the floor with all your strength, moving your hands towards your feet rather than forwards. This movement engages the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis) and the hip flexors, especially the iliopsoas, but also the rectus femoris in the front of the thighs.

- Try to reduce flexion in the hip joints and frontal abduction in the shoulder joints as little as possible.

Details

- The pose can certainly only be held at full intensity for a few seconds at first, then reduce the intensity a little so that you can perform the pose for at least 10-15 seconds.

- There should be no tendency to cramp in the rectus femoris muscle. The abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis) may work significantly. However, a large part of the work in this pose comes from the hip flexor group, which moves the upper body and thighs towards each other. This movement feels like pulling the ischial tuberosities upwards and acts as flexion in the hip joints, which subjectively increases the pressure of the hands on the floor.

- The work of the arms slightly counteracts the desired frontal abduction in the shoulder joints. This is clear and normal, as the type of work here is completely different. However, the work in the hip joints remains the same and is even more intensive here.

- Since the movement of pushing the hands towards the feet is not accessible to everyone, especially in view of the apparent impossibility of a visible movement, you can firstly remember the „pull-overs“ from strength training (lifting the dumbbell corresponds to the movement to be performed) or also build up the pose from a downface dog, in which the hands are immediately pushed forcefully towards the feet, even while the knees are still resting on the floor when building up the pose, see the variants hands on carpet. Dorsiflexion of the ankles is also made more difficult. Nevertheless, keep the dorsiflexors inactive.

Push hands towards each other

The emphasis here is on working the pectoral muscles (pectoralis major) and the biceps brachii (arm biceps) as well as the deltoid, pars clavicularis. This is a very helpful variation for people with a tendency to overstretch their arms.

Instructions

- From normal downface dog, start to push the hands towards each other with increasing force. As this is done against the friction of the support, there will be little external movement, but there will be strong work on both sides in the pectoralis major, deltoideus pars clavicularis and biceps brachii muscles.

Details

- When a certain amount of force is used to push the hands towards each other, muscular work begins in the arm biceps which relieves the strain on the outside of the elbow joint when the arms are hyperextended. Such relief is definitely achieved by this movement if it is performed with sufficient force, even if it is not yet apparent that the elbow joint has reached 180 degrees again after initial hyperextension. This effect is based on the fact that the short head of the biceps (caput breve) is acquired in its transverse adducting action when sufficient force is applied.

- This is interesting and unusual work for the arm biceps, as the angle in the elbow is a stretched one. When performed strongly, you may be able to feel the biceps in the elbow area up to its attachment to the radius.

- The use of the biceps should not cause the arm to bend in the elbow joint (angle less than 180°), otherwise the triceps must be used to restore and maintain extension, which allows the upper arm muscles to work quite completely. You should also maintain the full external rotation of the arms. Particular attention must be paid to this, as the pectoralis major and deltoid muscles, pars clavicularis have an internally rotating effect in the shoulder joint.

- If a tendency to cramp in the pectoralis major is felt, the intensity with which the hands are pushed towards each other must be reduced.

- The transverse adduction performed may press the inside hands better onto the floor. However, this is not an adequate solution to the „mouse hole issue“.

Tighten your biceps

Learn to specifically avoid hyperextending your arms and any associated pain in the dorsal elbow.

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above

- Tense the biceps in both upper arms and, if the elbow joints are hyperextended, bend them using the strength of the biceps until the 180° angle is reached.

Details

- The ability to hyperextend the elbow joints is individual and some people experience pain in the dorsal elbow joint under load, which is why it makes sense to learn to specifically avoid hyperextending the elbow joints. There is often little voluntary control over the elbow joint in the overhead position of the arms and it is not easy to bring the elbow joint back to 180° from hyperextension in a permanent and stable manner. The best way to achieve this control is to use the arm flexors, for example the biceps, even if the brachialis is the stronger flexor in some cases. It has been observed that in the overhead position of the arms many people are unable to tense the arm flexors voluntarily or find it difficult to do so. The following procedure, which is also described in the functional exercise tensing the biceps, can be helpful in acquiring this ability:

- sit comfortably and extend the right arm sideways with the inner elbow pointing upwards, palm and biceps through.

- bend the arm to 90° at the elbow joint, tensing the biceps very forcefully, as bodybuilders do when posing, for example. Naturally, the biceps and triceps work equally as agonist and antagonist in a fixed angle position, otherwise a movement in the elbow joint would result. You should be able to feel the tension in both muscle groups.

- slowly extend the arm without losing the tension in the biceps. The further the arm is extended, the more difficult it will be to maintain the tension in the biceps.

- turn the forearm into pronation (palm down), again without losing the tension in the biceps. This step also requires a lot of attention and strength. Most people are completely unaccustomed to tensing the biceps and keeping them tensed when the elbow joint is extended, especially if the forearm is or will be pronated.

- suddenly release the tension in the biceps and restore it in a flash, interrupting it for as small a fraction of a second as possible.

Repeat this several times, gradually extending the time the biceps are not tensed, and continue to release and tense the biceps with the elbow joint extended and the forearm pronated, slowly bringing the arms into an overhead position.

- Practice this with each arm separately before practicing it with both arms at the same time. If you practise this several times, you should be able to tense the flexors in any overhead position of the arms. The effect of this tension is a change in the balance of forces in the elbow joint, which cancels out the effects of the hyperextension or the hyperextension itself. Of course, this tension is very unfamiliar and it takes some practice to develop the necessary control and strength, but then a safe and very effective tool is available to avoid hyperextension regardless of its extent and effect. This method of avoiding hyperextension is far superior to pushing the hands towards each other because it

- develops much more body awareness and control in the region concerned

- trains the muscles of the arm flexors

- is universally applicable and does not depend on the presence of a wall or floor on which the hands could be pushed towards each other

- also works in positions of the arms other than their overhead position, e.g. with an unloaded arm in second warrior pose, with a moderately loaded arm in trikonasana, woth a heavily loaded arm in vasisthasana and ardha vasisthasana.

It is therefore worth the effort to learn this technique.

- develops much more body awareness and control in the region concerned

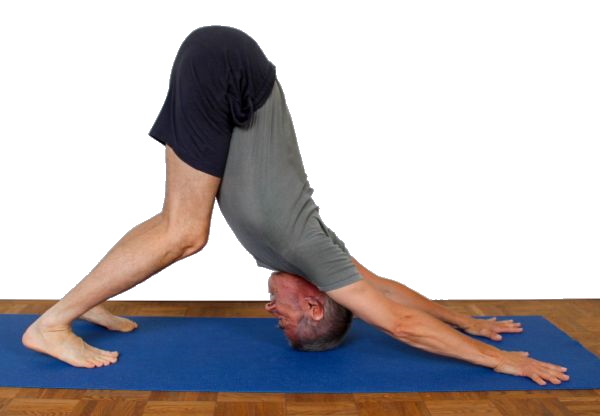

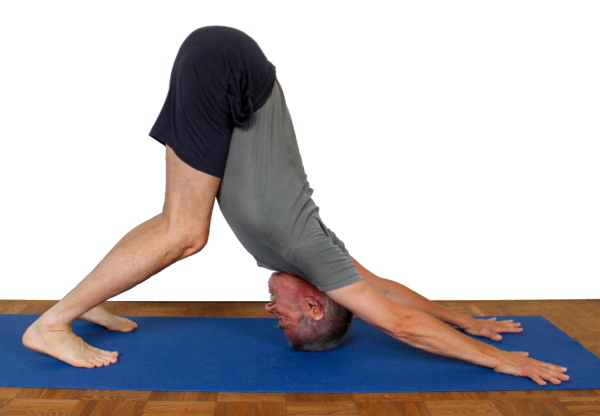

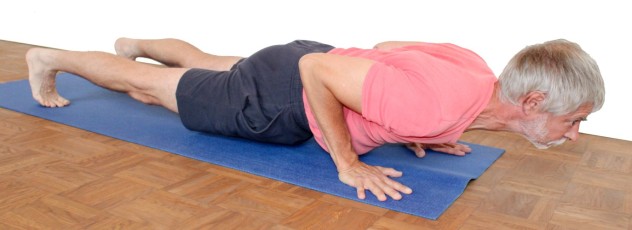

Head on the ground

This variation is impossible for people who are immobile in the shoulder joint in the direction of frontal abduction, especially if the hamstrings are also less mobile. It allows greater work in the arms and back when the head is almost weightless on the floor or hovering just above the floor. At the same time, it is of course a clear „shoulder opening“, i.e. a pose that promotes flexibility of the shoulder joint. Perhaps the most interesting effect is the ability to roll your head a little further back after placing the head, to give your neck a gentle stretch. This exercise also serves as a preparation (recommended only for more advanced performers) for the complex of shoulderstand-related poses and the dog headstand.

Instructions

- Take downface dog with only a slightly greater distance between hands and feet (for people who are mobile in the shoulder joint) or a significantly greater distance (for less flexible people), depending on the flexibility of the shoulder joint.

- Stretch your trunk backwards strongly from the shoulders.

- Now – without releasing the pressure backwards – lower your shoulders further until your head has reached the desired position. Be sure to turn your arms out strongly and stretch out from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades). If necessary, carefully transfer weight from your head to the floor. If you place your head on the floor, choose the same area as in headstand.

- If necessary, carefully roll backwards on your head, only a few millimetres at first. Observe the back of the neck and move carefully to just before the assumed limit of the neck.

Details

- This exercise should not be used by beginners and people with neck problems unless recommended by and under the supervision of a professional. Careless execution can lead to neck problems.

- If used correctly, this pose can possibly relieve tension in the neck muscles, but not the relatively common chronic cramps of the trapezius, which can hardly be treated effectively in any other way than with prolonged pressure on the muscle transversely to its longitudinal direction (see karnapidasana on rollers) and, of course, improvement of habitual factors.

- Make sure that your hands and feet are resting on a secure surface and that no sudden slipping can endanger your neck

- Keep your arms powerfully active to be able to dose the desired effect on your head and neck safely and sensitively.

- This variant is not recommended for those who have the shoulder flexibility but lack the strength to control and safely dose the pressure exerted on the head.

Raise and lower wrists

Switch between …

This pose is an effective exercise for strengthening the forearms. In many cases, it may be impossible for beginners to perform for some time

Instructions

- Take the downface dog.

- Shift the weight from the wrists to the area of the base joints of the fingers; the wrists should become noticeably lighter.

- Increase the pressure evenly until the wrists lift, both at the same time.

- In the final position, the base joints of the fingers are only moderately concave, the weight rests on the index and middle fingers and their base joints, fingers 4 and 5 and the thumb are raised. Whether the wrists are convex or concave from above (on the back of the hand) depends not least significantly on the flexibility of the shoulder joint and secondarily on that of the hamstrings and, of course, the distance of the hands to the feet.

Details

- Although it seems as if you are hanging in the metacarpophalangeal joints in an unhealthy way, this is not the case, as there is no significant flexion moment (and in no case an external moment, as in other comparable poses in this respect) in the direction of increasing the angle in the metacarpophalangeal joints, but this angle is maintained at all times by the body’s own muscle strength (except perhaps in people with extremely worn metacarpophalangeal joints, who can place the palm on a steep angle with the metacarpophalangeal joints upright). Furthermore, the backward pushing movement still takes place (the opposite would be necessary for a destructive external moment).

- Don’t fail to turn out the arms of the arms or to stretch the elbow joints.

- Make sure that the shoulders do not come forward or upwards during and after the attempt to lift the wrists. This would be an unacceptable relief.

- Raise your wrists simultaneously and evenly. Synchronize their movements. This may be impossible at first due to a lack of strength in some forearm muscles (palmar flexors). Then take the pose by lifting one wrist at a time and practise lowering your wrists at the same time in as controlled a manner as and as slowly as possible.

- If it is not yet possible to lift off at the same time, it is advisable for an assistant to provide the necessary strength so that a feel for this unusual movement can be developed. This is best done by pulling on the hips as described in the details of the variant with a supporter.

- Be careful not to roll onto the outside hand first before lifting the wrists, but lift the inside and outside simultaneously and evenly.

- Work without momentum, but from a slow, steady build-up of strength. Momentum is usually intended to replace strength in order to overcome obstacles or achieve results. This principle is not required here, but rather the repeated decision that

- more and possibly even more force can be made available and used and

- the result is possible now and for you.

In this sense, the exercise is very interesting from a psychological point of view.

- Often, if there is a lack of strength, first one wrist and then the other is lifted off the ground. This may be acceptable as a very first step. Initially, it can be useful to bring the wrists into the raised position however possible and then attempt to lower them synchronously; after all, muscles develop significantly more in the eccentric contraction (see force-length function).

- Slowly move from the outer hand towards the inner hand until the little finger and ring finger lift off. Then try to lift the thumb as well.

- The pose is also heavy because the forearms are usually in maximum pronation with additional slight dorsiflexion of the wrist. This makes the work of the flexor carpi radialis more difficult due to an unfavourably great sarcomere length.

one-handed

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above

- Increase the force exerted in one arm and lift the other hand off the floor to place it on the sacrum or pelvis.

Details

- Not only does one arm and the muscles in the torso that move it have to work much harder and be strengthened, the asymmetry also brings new aspects to this pose, for example the oblique abdominal muscles have to work or the pectoralis major is felt here for the first time as a stabilizing muscle. This is also the result of the fact that the gravity perpendicular is no longer centered in the physical support base.

- Do not allow the arm to turn in. The tendency to do so results from the use of the largely internally rotating frontal adductors of the shoulder joint, such as the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and teres major, whose effects on the position of the upper body no longer partially cancel each other out, as in symmetrical poses.

- The muscles moving the upper arm have to work much more than twice as hard here as in the two-armed version and some muscles may also have to work for the first time in a variation of downface dog.

Heel on the ground

This position brings more stretch to the back of the leg, esp. the gastrocnemius.

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- From normal downface dog, slowly push your heels towards the floor.

Details

- Make sure that the inner heels move downwards just as forcefully as the outer heels. Pushing the inner heels down (and thus stretching the inner calf muscles) is particularly important for anyone who is prone to shin splints or does a lot of running.

- As the total length of the muscle systems between the ball of the foot and the ischial tuberosities (seen across all three joints) is naturally the same in this variation as in the normal version, there is an inevitable tendency to slacken a little in flexion in the hip joints as the heels are pushed down. Not that this can be avoided, you should just be aware of the effect when transitioning from one variation to the other and be aware of its extent in order to gain insight into other variations. It will usually be the case that the two movements (flexion in the hip joints and lowering of the heels) prove to be non-commutative (interchangeable in sequence), i.e. depending on the order in which the movements are performed, the result will differ slightly.

- The lateral position of the heels should be chosen so that it corresponds approximately to the middle of the forefoot, i.e. the imaginary midfoot lines are parallel. The tendency described above to stand more on the outer feet is often accompanied by the heels coming closer together. It is more correct to keep the heels further apart, as this corresponds to a minimal internal rotation in the hip joint, which makes hip flexion a little easier.

- Together with warrior 1 pose and parivrtta trikonasana, this pose is one of the most useful stretches for the gastrocnemius. Although only around a quarter of the body weight is effective here, this variation can be held for a relatively long time.

- Note that the knee joint must be fully extended for good stretching of the calf muscles due to the biarticularity of the gastrocnemius. As should be easy for anyone to see, the (loaded) ankle joint can be brought much further into dorsiflexion when the knee joint is flexed, because in this case only the muscular restriction of the soleus plays a role, but not that of the gastrocnemius. If the knee joint is then extended, the gastrocnemius pulls the foot a little out of dorsiflexion via the Achilles tendon. With this in mind, the exercise can also be practiced alternatively or better additionally in such a way that the heels are first placed firmly on the floor with the knee joints clearly bent and then an attempt is made to extend the knee joints, if possible without making the heels lighter, although this requires good flexibility of the gastrocnemius.

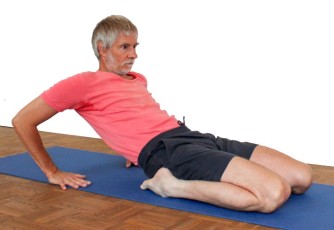

Knees bent

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Bend your knees clearly and try to press your upper body onto your thighs.

Details

- This variation relieves the hamstrings to such an extent that with good flexibility contact may be established between the abdomen and thighs. Due to the bent knee joints, the pelvis tilts much further into flexion in the hip joint, very noticeable esp. in those who are less flexible in the hamstrings, so that the back becomes straighter and can be positioned more steeply. This often gives a feeling for the work to be done in the shoulders and arms for the first time.

- This variation may enable less mobile people in the hamstrings to perform the exercise without any problems if they have a herniated disc in the lumbar spine. Painless execution can be expected if it is possible to keep the lumbar spine in physiological lordosis. It may be necessary to increase the distance between the hands and the feet. In many cases, a steep position of the lumbar spine is still tolerable. If, in addition to the shortening of the hamstrings, the shoulder joint is not very flexible in the direction of frontal abduction, the distance between the hands and the feet will have to be increased in any case.

stretch from bent knees

This variation allows you to achieve better flexion in the hip joints.

Instructions

- Take downface dog as described above.

- Bend the knee joints and keep tilting the pelvis forwards and downwards (into flexion in the hip joint) until the abdominal wall or the lower rib bones come to rest on the thighs. If possible, press these body parts firmly together.

- Build up strong backward pressure in the arms and begin to stretch the legs so that the position of the shoulders, upper body and pelvis is at least largely maintained.

- Repeat the last two points several times.

Details

- As already discussed elsewhere, the individual movements that make up a pose are not necessarily commutative (interchangeable in sequence). This fact is exploited here to achieve better flexion in the hip joint.

- This variant is a possible alternative if there is irritation of the origins of the hamstrings at the ischial tuberosities (PHT), often as a result of a weak constitution and frequent practicing of forward bends in beginners), as already discussed in the FAQ.

- Maintaining the position of the pelvis is powerful work in the hip flexor muscles. The rectus femoris is part of these. With the hip joints in almost maximum flexion, the rectus femoris being involved in extending the knee joint, it works in a very short sarcomere length and can therefore tend to cramp. Then try to work subjectively more with „pulling up“ the ischial tuberosities in order to keep the pelvis tilted forward as much as possible (maximum flexion in the hip joints). This often results in a shift of the forces flexing the hip joint shifting away from the rectus femoris towards the iliopsoas.

- Ideally, the position of your shoulders and upper body should not change as you straighten your legs, which is generally almost impossible. To get as close as possible to this ideal, focus on pushing your shoulders back as far as possible and – in contrast to the normal downface dog – downwards.

- Stretching the knee joints should be done slowly and carefully and will require some strength if the hip flexors and arms are used vigorously. As the extension of the knee joints increases, the stretch in the back of the leg (hamstrings) must also increase. If the exercise is performed well, fully extending the legs is almost impossible and requires a lot of strength and time.

- With only average flexibility of the hamstrings, this is a fairly safe method of protecting the knees from hyperextension and the associated pain.

Shrug

This variation makes the movement of stretching from the shoulders clearer.

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above and stretch backwards and upwards from the shoulders as far as possible.

- Keep the pose exactly as it is but give up stretching from of the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) backwards and upwards so that the shoulder area and with it the upper body will slowly sink to a maximum in the direction of the wrists, i.e. to the maximum depression of the shoulder blades according to gravity.

- Now slowly stretch from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) backwards and upwards again to the maximum.

- Repeat the last two steps at least until the movement is completely clear and can be performed easily and at any speed.

Details

- In cases of significant flexibility restrictions in the shoulder joints, the two states described above (stretched from the shoulder, i.e. elevated, and sunken, i.e. depressed) may appear to be identical from the outside. In some cases, the performer may have made a voluntary effort to move to the other state, but the impulse may be completely absorbed by the resistance created by the antagonistic muscles. In other cases, the performer does not even realize what he is supposed to do, not least because he cannot recognize any of the described options for action. Before this attempt is prematurely abandoned, an assistant should first try to support the performer in the movement (elevation) by periodically applying and releasing tension on the pelvis or thighs. It makes less sense to support the depression, as experience has shown that the angle of frontal abduction in the shoulder joint deteriorates as a result. This is probably mainly due to the fact that in the cases described, the condition of the shoulder blades is consistently depressed, as they are held in this position by a less flexible antagonist of frontal abduction, the latissimus dorsi, which is also an indirect depressor of the shoulder blade.

- The sunken (depressed) state can be perceived as less pleasant than the extended (elevated) state, as there tends to be a greater tendency for the trapezius to cramp.

- Be careful not to confuse sinking (depressing) with bending the elbow joints, but to keep them constantly stretched using the strength of the triceps; the elbows are consciously moved towards each other – unless there is a risk of hyperextending the elbow joints.

- Make sure that you do not lose the external rotation of the arms, which can often be observed when the arms are fully extended (elevation) and is due to the resulting tension on the internally rotating latissimus dorsi.

- The movements should be able to be performed at any speed, especially not just jerky, but also slowly flowing – also for better control over the extension and external rotation of the arms.

- The shoulders often move forwards or forwards and upwards when sinking in, which will be the case in particular with limited flexibility in the shoulders. An assistant can then be brought in to prevent this. If you are able to bring arms and trunk in a commone plane in downface dog, neither trunk nor arms are to leave this plane. If there is even better flexibility and the angle of frontal abduction is greater than 180°, the arms and back should generally remain in their own planes during the movement undertaken here.

- Even if it is not primarily about the work in your hands, try to keep your hands completely still and do not relieve the inner finger joints in between.

Chest to one leg

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Move your chest towards your right leg.

Details

- This variation is deliberately asymmetrical, which increases the stretch in one shoulder joint and in the hamstrings and possibly the gastrocnemius of one leg.

one leg bent

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Bend one leg significantly or lift the foot off the floor and hook the leg or foot behind the counterlateral knee.

- Let the heel of the remaining standing leg on the floor sink further towards the floor and tilt the hip into maximum flexion.

Details

- Here the load is shifted to one of the two legs, which means increased stretching both in the hamstrings of the same leg and in the calf muscles, in particular the gastrocnemius due to the stretched knee. After all, the load of the body (or about half of it) is no longer carried by two calves but only by one and this must also carry the load of the other leg.

- In some cases, the heel of the standing leg comes to rest on the floor. A distinction must then be made: if the stretching sensation in the calf muscles is still very intense, the pose can be performed in this way; if it has decreased as a result, the distance between the hands and one foot on the floor should be increased until the heel is again hovering just above the floor and can move towards it.

- In rare cases, the resulting stretch in the calf is perceived as too severe, which is likely to be in relation to the muscular robustness of the calf. In this case, the pose must be varied and softened in such a way that there is no risk of cramp resulting from overstraining, either by only slightly (!) actively holding the heel up or, better still, by reducing the distance between the foot and the hands or by using a small pad under the heel. In cases where this necessity arises, poses that strengthen the calf muscles should be practiced more often, such as warrior 1 pose, parsvottanasana, parivrtta trikonasana, vrksasana (the tree) and also warrior 3 pose, including backwards against the wall. However, this phenomenon not only affects less robust calves but also very stiff ones.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Tendency to cramp with weak calf muscles

As already described in the details, a tendency to cramp can occur with rather weak calf muscles under intensive stretching with a high load. This should of course be avoided and any cramps that arise should be stopped immediately. To counteract this tendency, the calf muscles should be strengthened; various sporting activities are generally suitable for this, but especially the standing poses described above, as they provide more strength endurance while maintaining or even increasing flexibility. Sports or activities in which the strengthening is more peak-like, such as jogging and running, are less suitable for strengthening.

one leg stretched out in front (hip opener 5)

One-sided, intensive stretching of the hamstrings.

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Bring the right foot forward, approximately in the middle between the hands (i.e. the heel at wrist height).

- Press your upper body as much as possible onto the thigh of the front leg.

- Maintain the contact you have just made and now slowly extend the front leg so that contact is not lost or at least the distance remains as short as possible.

Details

- The front leg tends to turn out, prevent this by moving the inside knee and the inside foot downwards forcefully.

- Due to the course of the dorsiflexors, the front inner foot tends to become lighter or even lift off with supination in the subtalar joint, so consciously press it down firmly, which also facilitates the above correction.

- The back leg remains according to the downface dog, i.e. the foot points straight back, the heel moves towards the floor.

- It is possible for almost all people to establish more or less strong contact between the thigh and upper body after the leg has been pulled forward, but for beginners, especially those with little flexibility in the hamstrings, it is often not possible to maintain this contact when extending the front leg; it is often lost after the first 20° of further extension in the knee joint (compared to the starting position with the upper body on the thigh).

- The hip belonging to the front leg should be moved backwards and upwards so that the pelvis remains straight and does not turn away as an evasive movement of the front leg.

- This variation is easier to perform if forward bends such as uttanasana are performed beforehand.

- The forehead may be placed on the lower leg and remain there while the leg is extended.

- Even in this position, push both feet away from each other.

- This variation, performed correctly and with the feet well apart, is one of the best stretches for the foot lifts alongside baddha padasana. The stretch can be felt mostly in the muscle bellies of the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus, but also in their insertion tendons on the back of the foot up to the dorsal big toe.

narrow