Contents

- 1 adho mukha vrksasana„handstand“

- 2 Variants

- 2.1 Shrug

- 2.2 Bend arms

- 2.3 Turn your arms the wrong way

- 2.4 on fists

- 2.5 on fingertips

- 2.6 Upswing without rotating leg

- 2.7 baddha konasana

- 2.8 supta baddha konasana

- 2.9 two-legged upswing

- 2.10 Do not move your arms

- 2.11 two-legged upswing as jumping

- 2.12 Dips

- 2.13 eka pada

- 2.14 free

- 2.15 Hands on the wall

- 2.16 Hands turned inwards

- 2.17 Hands turned outwards

- 2.18 Hands turned backwards

- 2.19 Push hands towards each other

- 2.20 Head and back against the wall

- 2.21 stand with your feet on the wall

- 2.22 with backbend

- 2.23 swing up with the unfamiliar leg

- 2.24 jump from maximum forward splits

- 2.25 only head against the wall

- 2.26 padmasana

- 2.27 padmasana Forward bend

- 2.28 supta padmasana

- 2.29 Bottom on the wall

- 2.30 Bottom against the wall, lower legs (dvi pada)

- 2.31 Shoulders to and from the wall

- 2.32 Shoulders towards the wall

- 2.33 Twist in handstand

- 2.34 virasana in handstand

- 2.35 krouncasana in handstand

- 2.36 look at your feet

- 2.37 look at the hands

- 2.38 samakonasana (side splits)

- 2.39 on blocks

- 2.40 two-legged lift with a block between the thighs

- 2.41 two-legged upswing with feet tied together

- 2.42 Wrists on patches

- 2.43 (P) free

- 2.44 (P) Support during the upswing

- 2.45 (S) eka pada

- 2.46 (2S) Butt against the wall, lower legs (dvi pada)

- 2.47 Transition to uttanasana

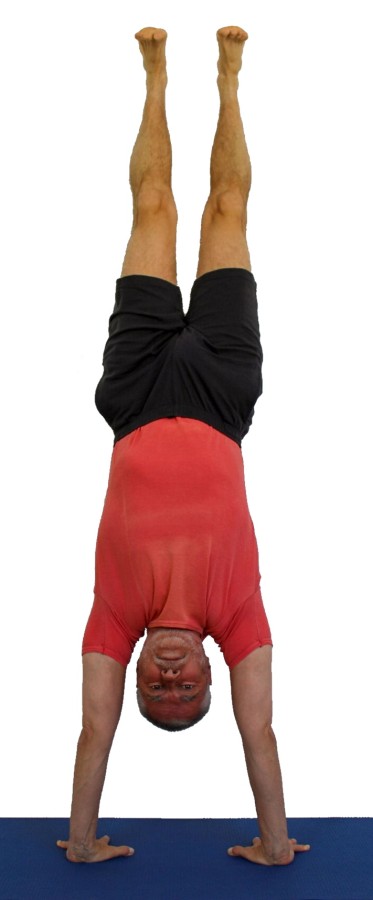

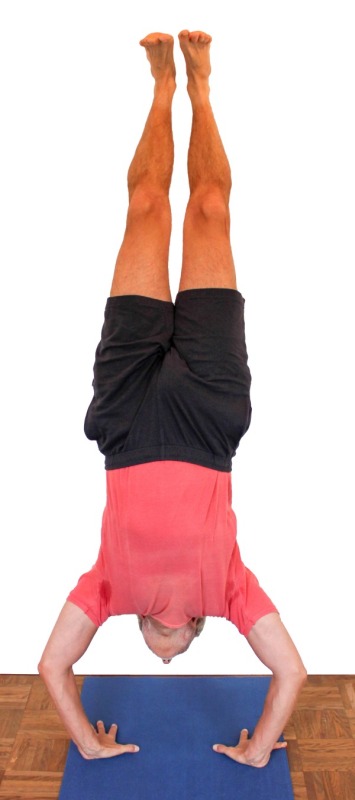

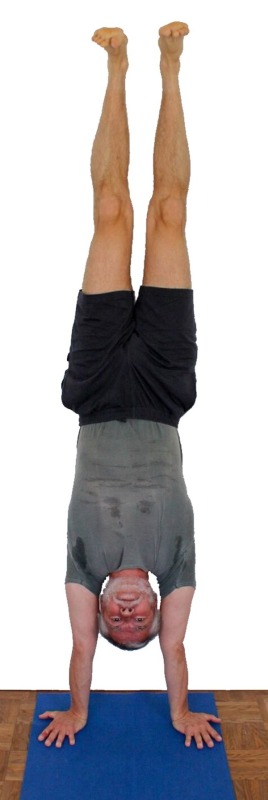

adho mukha vrksasana

„handstand“

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

Feedback: We’d love to hear what you think about this description, give us feedback at postmeister@yogabook.org

Last modification: 30.12.2018

Name: adho mukha vrksasana

Trivial name: handstand

Level: A

- Classification

- Contraindication

- Effects

- Preparation

- Follow-up

- derived asanas

- similar asanas

- Diagnostics

- Instructions

- Details

- Variants

Classification

classical: inversion pose

psychomental: energizing

physiological: arm and shoulder strengthening

Contraindication

When taking the pose, the familiar symptoms can flare up again in the event of an acute disc herniation of the lumbar spine. This is all the more true the less flexible the hamstrings are. The pose itself is not contraindicated, but taking it is very delicate. Only advanced performers can keep the lumbar spine straight during the two-legged upswing. Various desease and injuries can prohibit handstand.

Effects

- (423) Tone of the finger flexors

- (232) Strengthening the frontal abductors of the shoulder (deltoids, biceps, coracobrachialis): Maintaining the angle of frontal abduction against existing flexibility restrictions strengthens the deltoids in particular

- (292) Strengthening the trapezius: Elevating the shoulder blades against the body’s gravity strengthens the trapezius.

- (352) Strengthening the palmar flexors of the wrist: pressing down on the metacarpophalangeal joints strengthens the palmar flexors of the wrist.

- (302) Strengthening the triceps: stretching the arms against the flexion angle of the arms caused by flexibility restrictions strengthens the triceps, the more so the less flexible the shoulders are in terms of frontal abduction

- (332) Force for pronation of the forearm

- (352) Strengthening the palmar flexors

- (231) Stretching: frontal abduction shoulder: The overhead movement of the arms stretches the shoulders in the sense of maximum frontal abduction

- (321) Stretching to supination of the forearm

- (351) Stretching of the palmar flexors

- (341) Stretching for dorsiflexion in the wrist

- (351) Stretching the palmar flexors of the wrist: The angle of dorsiflexion of approx. 90° stretches the palmar flexors.

- (421) Stretching the finger flexors

- (501) Stretching the latissimus dorsi

Preparation

Warming up the hamstrings is an important preparation for anyone who doesn’t jump very easily into a handstand, so that no strains occur during the vehement swinging movement:

- uttanasana THE standard for warming up and stretching the hamstrings

- prasarita padottanasana similar to uttanasana

- downface dog good preparation with strong tilting of the pelvis

- parsvottanasana preparation beyond the uttanasana

- hip opener 5 preparation beyond the uttanasana

Depending on the flexibility and resilience of the shoulder, it may also be necessary to warm it up well:

- downface dog as a general stretch of the shoulder and hamstrings

- upface dog as a posture that prepares the shoulders for powerful work, especially through correctly executed transitions from and to downface dog

- rectangular handstand as a very related and highly synergistic pose

- back stretching, especially the „elevated“ version as a general stretch of the shoulder and hamstrings

- dog elbow stand as a related pose, which differs mainly in the rotation of the arms

- hyperbola as one of the most effective and efficient stretches in the direction of frontal abduction without turned out arms

- Shoulder opening on the chair as one of the most effective and efficient stretches in the direction of frontal abduction with turned out arms

- purvottanasana if the tone in the anterior deltoid is too high or has become too high due to preparation

To prepare for work in the shoulders with a similar movement without fixed hands:

- upavista konasana with block makes you aware of the type and intensity of work in the shoulders

- dandasana with block between raised arms, like upavista konasana with block

Preparation of the palmar flexors of the forearm in terms of pre-activation

- tolasana

- ardha vasisthasana

- vasisthasana

- rectangular handstand

- downface dog, transition to upface dog an back

„Energetic“ preparation for all those whose upswing fails due to unconscious or partially conscious internal factors that are not rooted in the musculoskeletal system:

- surya namaskar (the sun salutation) stimulates the flow of energy and clears the mind a little

- rectangular handstand gets you used to losing the ground under your feet

Follow-up

In cases of significantly restricted flexibility in the shoulder joints, a more or less pronounced hollow back can occur. In order to eliminate the resulting discomfort, the following poses can be performed symptomatically to reduce the tension in the muscles of the lumbar spine:

- uttanasana, especially the „parsva“ variation

- parsva upavista konasana

- parsvottanasana

- downface dog

- hip opener 5

If there is discomfort in the dorsal wrists after handstand due to the limited ability to dorsiflex the wrists, it may be necessary to use the poses, which can also be used as preparation, as a cure:

- Forearm stretching for the palmar flexors to stretch the muscles in the wrist that perform the stretch

- Forearm stretching for the dorsal flexors to prevent the antagonists of the executing muscles in the wrist from cramping

- Forearm stretch in upavista konasana for the palmar flexors for further stretching of the wrist muscles

Derived asanas:

Similar asanas:

As an inverted posture:

General:

Geometry:

Effect in the shoulder:

Diagnostics (No.)

Handstands can reveal weaknesses in the wrists:

- Ganglion in the dorsal wrist area: the ganglion is a proliferation of tissue that can cause pressure pain

- Shortening of the palmar flexors: in addition to stretching sensation on the palmar side, this also causes pressure in the dorsal wrist area. Stretching usually improves the situation.

- Tendency to cramp of the dorsiflexors of the wrist: these develop a tendency to cramp in their tendon area in the wrists and distal forearm. Stretching usually improves.

(354) Forearm:

A golfer’s elbow can be noticeable when standing on the hand: Pain in the inner elbow (more precisely in the area of the medial humeral epicondyle) in the area of the tendons of the palmar flexors usually indicates a more or less pronounced epicondylitis humeri ulnaris („golfer’s elbow„). In every day life, rest before exerting greater force, especially of the impact type, and regular, rather gentle and prolonged stretching are then indicated as well as additional rehab training to promote blood circulation and strengthening. See golfer’s elbow and insertional tendopathy.

(724) Back of the leg:

During a handstand, especially the upswing, irritation of the area of origin of the hamstrings at the ischial tuberosity (ischial tuberosity), a so-called proximal hamstring tendinopathy (PHT), can be noticeable: the area of origin of the hamstrings is stressed by the speed strength used for swinging when the hip joint is extended. These irritations are then particularly noticeable, even if they may be completely inconspicuous in everyday life (see FAQ).

(231)(232)(233)(234) Shoulder:

Various conditions and pathologies of the shoulder can become apparent in the handstand:

- Irritable hypertonus of the deltoid: especially ambitious beginners in yoga tend to develop irritation in the deltoid, which is localized in the area of the muscle origins, presumably due to an overstrain of the structures caused by frequently repeated demands in full frontal abduction and is also noticeable under such stress, see FAQ.

- pathologically increased tone of the trapezius, see FAQ.

- Various pathological changes of the shoulder joint such as impingement syndrome, frozen shoulder, calcifications of the biceps tendon, which cannot all be discussed here and require clarification.

- side discrepancies in flexibility

Furthermore, the handstand provides relatively good information about the flexibility of the shoulder in the form of the degree of evasion in the three dimensions of movement, recognizable as:

- Moving the upper arms outwards with (as the hands are fixed) consecutive bending of the elbows

- Loss of external rotation of the arms

- Insufficient angle of frontal abduction that does not reach 180° or does not reach it permanently

(101) Head:

Pain in the head can increase significantly in handstand. These can be:

- Latent headache can be significantly intensified under increased pressure. As the differential diagnosis of headache is very large and headache must be differentiated from migraine, it is not possible to go into this in detail. Sometimes a prolonged headstand, where the pain worsens slightly in the first 3-4 minutes and then subsides, helps against headaches of varying origin and intensity. Running also often helps very well. Running will be very unpleasant at the beginning, but the headache often starts to get better while you are running.

- Pressure on the eyes: increased intraocular pressure needs to be clarified.

- Latent or manifest colds can cause an increased sensation of pressure in the head.

- Pressure in the head due to a vascular system that has not (yet) adapted. It is advisable to practise headstand with precisely this focus, as the headstand can generally be held for much longer than handstand and therefore enables a much greater degree of adaptation.

(680) Esophagus/stomach/intestine:

A disturbed closure function of the stomach or esophagus can be particularly noticeable here, as can an overfilled stomach or intestine, which can exert pressure on the heart and lungs.

(302) Arms:

Low strength endurance of the triceps will be clearly evident if the shoulder is less mobile, as the triceps must limit the outward movement of the upper arms and the resulting bending of the arms.

(711) Pelvis (hip flexors, adductors):

Low flexibility of the hip flexors in a handstand may mean that it is not possible to create an extended angle (180°) in the hip joints, even if the extensors of the hip joint (e.g. the glutes) are doing their best. As a result, the upper body is tilted towards the legs, especially in the lumbar spine area, and there is often discomfort in the lumbar spine area. Shortened adductors with excessive tone would develop a tendency to cramp when the glutes attempt to eliminate the flexion in the hip joints because they have to absorb the external rotation moments of the pomus muscles, as can be observed even more clearly in the shoulder position.

(650) Kyphosis and lordosis of the spine:

The deviations from the physiological double-S shape of the human spine are better visible from the wall of from the side in this pose than from the front. There should be a certain degree of lordosis (convex spine from the front) in the lumbar and cervical spine and a certain degree of kyphosis (convex spine from the back) in the thoracic spine. The kyphosis of the thoracic spine can and should be removed in the sense of handstand and this area of the spine extended until it is stretched. See the FAQ. Restricted mobility of the shoulder (in the direction of frontal abduction) causes the upper body to tilt unfavourably in relation to the arms and legs, resulting in hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine.

(611) Pelvic obliquity/unequal shoulder height/scoliosis of the spine:

A lateral deviation of the spine from the sagittal plane, known as scoliosis, is also visible in this pose, but would be best seen from the wall, alternatively you can observe the linea alba instead. It is possible that both heels are unevenly high on the wall, the pelvis is noticeably slanted or the lower ribs are unevenly high, and possibly a slanted linea alba against arms and legs can be recognised in the frontal plane. If this is not the result of unevenly flexible shoulders, the spine is a possible cause. See the FAQ.

Variants:

Head and back against the wall

stand with your feet on the wall

Butt against the wall, lower legs (dvi pada)

Shoulders to and from the wall

two-legged lift with a block between the thighs

two-legged upswing with feet tied together

(S) Support during the upswing

(2S) Butt against the wall, lower legs (dvi pada)

Instructions

- Take downface dog.

- Place one foot (the corresponding leg becomes the „jumping leg“ and for taking the pose will be the standing leg) with the knee joint bent about 30 cm forward and put most of your weight on this foot.

- Lift the other leg (the „swinging leg“, a free leg) off the floor, keep it extended and swing it up and down several times in succession.

- On a strong swing up, decide to also jump off with the other leg. Keep your shoulders sufficiently away from the wall during the upswing.

- When handstand is taken, use the strength of the arms to stretch upwards to the maximum, also elevating the shoulder blades to the maximum (moving away from the pelvis).

- Keep the shoulders moving away from the wall in every phase, even if this makes it more difficult to take the pose, especially the upswing.

Details

- For people who are inflexible in the back of the leg (hamstrings), it is necessary to warm up these muscles well, e.g. by doing a downface dog or forward bends such as uttanasana, in order to minimize the risk of straining the muscles when swinging the leg up vigorously. The less practiced the performer is, the more vehement their swinging movement will often have to be in order to be able to take handstand. However, the vehement swinging movement in particular is a clear demand on the muscles and tendons of the hamstrings. Adequate stretching and warming up of the muscles before handstand and additional strengthening exercises, regardless of the execution, should significantly reduce the risk. The performer will later be able to take the handstand with minimal momentum or even without any momentum at all, so that the risk of straining the hamstrings is no longer present.

- Avoid the frequently observed bending of the swing leg when swinging up, as this has two disadvantages:

- the momentum that can be achieved with this leg is reduced with increased bending of the leg because the effective lever arm is reduced as a result.

- when the leg is bent, there is a tendency to push off the wall again when the foot reaches the wall, as with a bent leg the foot usually reaches the wall before the center of gravity is above the hands or between the hands and the wall.

- Beginners may find it difficult to control the movement of the body towards the wall when jumping up, which is transmitted to the shoulder area, i.e. to keep the shoulders at a sufficient distance from the wall so that the head does not hit the wall. For most people there is a „point of no return“: once the shoulders have passed a certain point, you are no longer able to bring them back and are forced to leave the pose uncontrolled, often frightened and collapsing with a corresponding risk to the cervical spine and head. Another difficulty resulting from this movement is the reduction of the dorsal external angles in the wrists: for most people, the angles of dorsiflexion of the wrist resulting from the uncontrolled movement of the shoulders exceed the available amount of extension and strength at this angle.

- A challenge for many people is the constant, possibly not insignificant use of strength in the arms, especially if the shoulders are quite immobile: the more immobile the shoulders are, the greater the tendency to bend in the arms, so the more strength is required. Stiff shoulders force

- bending in the arms

- an insufficient angle between the upper arms and upper body

- an internal rotation of the arm or reduction of the extension

The first two of these require many times more effort than would normally be necessary for standing in handstand and the last one poses a risk if the shoulder joints are unstable.

- A major problem for many people is overcoming the challenge of lifting their feet off the ground to stand upside down on their hands. This clearly shows the influence of psychological factors on the performance of the physical body. In some cases, it takes years for a performer to get into handstand on their own for the first time without assistance, even though the physiological factors such as flexibility and strength have been in place for a long time. Even after handstand has been successfully performed alone one or more times, there may still be occasional slumps before the whole phenomenon stabilizes to the point where you can almost always get into handstand on the first attempt.

- Handstand is easier to take and hold when the hands (and upper arms in the shoulder joints) are turned outwards. Please note, however, that the stretching and strengthening effect on the shoulders is reduced and the necessary balancing also changes, in the sense that it requires a little more attention to balance in a forward/backward direction, partly because the base of support is reduced. What is more serious, however, is that the more the hands are turned out, the greater the loss of the ability to keep the shoulder and therefore the rest of the body away from the wall by pressing the palm of the hand downwards using the strength of the palmar flexors in the forearm! Don’t underestimate this effect, especially as a beginner, but learn by slowly turning your hands out further and further how this changes your pose and, above all, how you can still hold it safely.

- An important movement is the stretching from of the shoulder (elevation of the shoulder blades), i.e. the utilization or expansion of the range of motion (ROM) of the shoulder blades in the scapulothoracic sliding bearing, which (if the arms are not in the overhead position but next to the body, e.g. in standard anatomical position) corresponds to the shrug, i.e. the movement of the shoulder blades on the back in a cranial direction (or as a repeated movement alternating with the movement in a caudal direction). To do this, without changing the angle between the legs and pelvis or between the upper arms and upper body, try to push the heels up the wall using the strength of the muscles required for the „shrug“, i.e. primarily the trapezius and levator scapulae, i.e. convert every exertion of the aforementioned muscles directly 1:1 into a movement of the heels on the wall.

- When being assisted by a supporter, the following must be observed when swinging the legs up:

- the swinging leg represents a potential danger to the supporter. Contact between the swinging foot and the supporter’s head can result in serious injuries, including loss of consciousness.

- If the performer is only helped by the leg, there is a risk that the force applied will be transferred to the performer’s shoulder and push it towards the wall. If the performer does not have the necessary flexibility in the shoulder joint or does not have sufficient orientation as to which movements are necessary, he will translate the applied force into a evasion of the shoulder towards the wall (instead of moving the legs and pelvis further towards the wall, increasing the angle in the shoulder joints and decreasing the angle in the hip joints) and lose the support to continue holding on to the arms. It is therefore necessary to limit the movement of the shoulder towards the wall for a while, e.g. by using a hand or knee to prevent it from moving too far towards the wall. It should also be noted that a passively raised leg causes rotation of the upper body and shoulders and therefore puts more strain on one shoulder or the corresponding arm.

- People who are infelxible in the shoulder tend to stand in handstand with a hollow back. This is the result of the angle in the shoulder joints remaining significantly less than 180°, which prevents the upper body from reaching a vertical position (and certainly from tilting further towards the wall). As the heels are against the wall, a bend must occur somewhere between the shoulders and feet. This usually occurs in the lower back because, firstly, the flexibility of the lumbar spine is much greater than that of the thoracic spine, secondly, in most such cases the thoracic spine (in which a backbend could also occur) will not necessarily be flexible and, thirdly, the possibility of extension in the hip joints (or at least sufficient reduction of flexion) will usually not be sufficiently available. Affected performers often leave the handstand with a tense feeling in the muscles of the lower back, but in most cases this is harmless and can be remedied in the short term with poses such as downface dog or, even better, 1st hip opening. The supporter should therefore also try to increase the angle between the upper body and upper arms, not simply by pushing the upper body towards the wall, of course, but by applying this same pressure at the same time countering it in the shoulder area, for example by holding the shoulders or slightly pulling on the shoulders with the hands and pushing the upper body against the wall with the head in the area of the upper abdominal muscles (just distal to the origin of the rectus abdominis) with simultaneous traction on the shoulders.

- These factors must be taken into account when practicing with or without assistance.

- Straightening the upper body, i.e. increasing the angle of frontal abduction in the shoulder joints, is one of the essential efforts in handstand, at least until great shoulder flexibility is achieved. After that, the focus should be on stretching from the shoulder (elevation of the shoulder blades) or turning out the arms. See above for further comments on straightening the upper body.

- Free handstand is a variation that requires years of preparation when performed correctly in terms of even pressure distribution between all the metacarpophalangeal joints and between these and the wrist area. There is an extreme relationship here between the external moment occurring during balancing, resulting from the maximum length of the lever arm (in this case the length from the heels to the wrists) and the weight present (exactly the whole body weight minus only the weight of the hands) and the means available to manage it, namely the lever arm of the forearm muscles for palmar flexion and dorsiflexion (in the wrist this lever arm is in the order of approx. 10 cm) multiplied by the force that the forearm muscles can exert (they are not „designed“ or trained for such loads). In addition, many people who are not particularly flexible in their wrists are in the area of maximum stretching, i.e. very long sarcomere length, and therefore have significantly reduced strength and performance of the forearm muscles, apart from the stretching sensation that may restrict exerting force. As with headstand, it is advisable to try to slowly and synchronously detach yourself from the wall with outstretched legs, in this case – in comparison to headstand – not from the strength of the skeletal muscles and pressure of the elbows against the floor from the strength of the shoulder muscles (deltoids), but also from the strength of the forearm muscles. It is therefore highly advisable to plan intensive pre-exercises to strengthen the forearm in preparation for free standing, as well as to ensure sufficient flexibility of the wrist in the direction of palmar flexion and dorsiflexion and to warm it up sufficiently.

- Even more frequently than in headstand, it is observed in handstand that the outstretched, swinging leg is bent shortly before reaching the wall during the upswing, which guarantees that the pelvis does not fall below a certain distance from the wall and that the center of gravity is not shifted from the wrists sufficiently towards the wall, so that the pose will not be not achieved. This is probably an unconscious mechanism to prevent control being taken away from the legs and given to the arms, i.e. an expression of fear of the pose and its imponderables.

- Swing into a handstand as quickly as possible. For the less experienced, swinging up slowly may result in the rotational moments in the spine (which propagate downwards from the pelvis in the direction of the head) acting on the shoulder area over a longer rather than shorter period of time and causing a certain tendency to tip over. Due to the inertia of the upper body, the time factor plays a role here. Another argument in favour of the fast upswing are the gyroscopic forces that stabilize the upswing depending on the speed.

- Do not look at the hands or wrists. This would suggest the wrong movement in the shoulder joint, namely to reduce frontal abduction. As a result, the upper body would usually tilt and a hollow back would develop. On the other hand, looking straight ahead or even beyond upwards (in spatial coordinates) promotes the correct movement in the shoulder joints, namely frontal abduction.

- Information on dealing with cubitus valgus can be found in movement physiology under axial misalignment.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Pain in the wrist occurs in many poses in which the wrist is at an angle of around 90° of dorsiflexion, e.g. upface dog. In addition to pressing the palm of the hand down more forcefully, stretching the palmar flexors of the forearm helps; the wrist can possibly be placed on a few patches so that the palm tilts a little and the angle of the necessary dorsal flexion is smaller.

A tendency to cramp in the trapezius

As with other overhead poses of the arms, a tendency to cramp in the trapezius can also occur here. This is almost always the result of a combination of several factors:

- insufficient flexibility in the shoulder joints, i.e. the ability to increase the angle between the upper arm and upper body, where the trapezius must rotate the shoulder blades outward, and to stretch from the shoulder (elevation of the shoulder blade) in the sense of a shrug.

- a high basic tension (tone) of this part of the trapezius, possibly combined with low resilience of this muscle.

- lack of external rotation of the arms or lack of ability to turn it out.

Pain in a hollow back: If the shoulders are not very flexible, the upper body may lean significantly against the arms (angle of snaller than 180°), resulting in a hollow back. The less you try to counteract this with your core muscles, the greater the pain will be felt.

Tendency to cramp in the deltoids: Depending on the tension in the trapezius, a tendency to cramp may occur in rare cases. This would be increased by inadequate external rotation of the arms and reduced by more vigorous external rotation.

Dizziness: this usually occurs when leaving handstand, mostly as a result of problems in the cervical spine or as a result of the changed circulatory situation: leaving handstand may lead to a deterioration in the good supply situation of the brain in the handstand, which requires counter-regulation until dizziness can occur. However, this should not last longer than a minute. If the dizziness lasts longer, the cause is often to be found in the cervical spine.

Variants

Shrug

Creates awareness for the movement of the shoulder blades on the back and strengthens the related musculature

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- After you have stretched from the shoulders (elevated the shoulder blades), as required in handstand, slowly lower the upper body again with the arms still stretched in the shoulders and raise it again. Establish a confident control of the movement and find the range of motion to gradually extend it further.

Details

- With less flexibility in the shoulders, the scope for shrugging is small to barely perceptible. The first step is to differentiate between the attempt to stretch from the shoulder and the pure slump in the shoulders, so that both can be clearly and purposefully elicited and alternated between the states.

- Often, and especially with less flexible shoulders, the exact stretching (elevation) movement in the shoulders cannot be precisely separated from the tilting of the upper body relative to the arms (a reduction of frontal abduction in the shoulder joints) or the extension of the arms or possibly a rotational movement of the arms in the shoulder joint. A supporter is then often needed for correction.

- Make sure that you don’t perform a movement in your upper body but keep it stretched so that stretching from of the shoulders is converted 1:1 into an upward movement of the heels on the wall.

- Depending on the nature of the wall, the sliding of the heels on the wall resulting from stretching from the shoulders (elevation of the shoulder blades) in particular will cause a perceptible noise combined with a vibration sensation at the heel. This is a good indication that you are working correctly.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Tendency of the trapezius to cramp: When you stretch forcefully from the shoulder (elevate) and repeatedly, the trapezius involved in the movement may become noticeable with a tendency to cramp.

Bend arms

This variation brings powerful work to the triceps and deltoids and, in addition to strengthening the shoulders and arms, can sometimes also be used – assuming sufficient strength – to reduce the cramp-prone tension in the deltoids that sometimes occurs after frequent practice of the downface down.

Instructions

- Take handstand the usual way. The hands should not be closer than shoulder-width apart, rather (for starters) a little further apart.

- Begin to bend your arms carefully. Depending on the exercises you have already done, give the triceps some time to warm up at the beginning to protect the elbow joint.

- When the triceps are warmed up and the elbow joint is no longer uncomfortable, start to bend further and hold the bend for longer.

Details

- In extreme cases, you can go from handstand to headstand and vice versa. Beginners are urgently warned against this! Even advanced performers should practise the transition from headstand to handstand for a long time until it has become a matter of course before they start practising the reverse transition, if this is at all desirable. The risk of damage to the cervical spine resulting in trauma and long-lasting dizziness is out of all proportion to the benefits of the transition from handstand to headstand!

- Make sure you don’t move in your upper body but keep it straight and also keep your hips 180° stretched the whole time, so that bending or stretching the elbow joints is converted 1:1 into an upward movement of the heels on the wall.

- It is not always easy to bend and straighten the elbows without tilting the upper body

- The ulnar (away from the thumb) side of the wrist may be noticeable when bending far, see below. Turning the hands in slightly can reduce the discomfort, as can a moderate increase in the distance between the hands.

- The distance between the hands should be greater than shoulder width for this variation so that the ulnar abduction in the wrist, which inevitably occurs when the arms are bent, is not too great.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Pain in the wrists: Particularly with far bending of the elbows, pain may occur in the ulnar-dorsal area of the wrist due to the compression of the structures. Apart from less bending, a greater distance between the hands or patches under the inner hands can help.

Pain in the shoulder: Depending on the training status and tone of the shoulder muscles, they could quickly become overstrained, possibly with a cramp-like touch. In this case, gomukhasana and the powerful transition between downface dog and upface dog can help.

Turn your arms the wrong way

Makes clear why the arms should be turned out.

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Now carefully turn the upper arms maximally inwards in the shoulder joints. When the maximum internal rotation is reached or the expected tendency to cramp in the trapezius becomes too great, slowly turn the arms the right way round again (turn the out).

Details

- This variation clearly shows why the arms are turned out and not in, at the same time the difference between the two states shows the range of movement.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

A tendency to cramp in the trapezius: Depending on the degree to which the upper arms are turned in in the shoulder joints, a tendency to cramp in the trapezius is not only possible but probable. This is precisely the purpose of this variation: to show why turning out the arms is so important, although the obvious effect is not the only reason.

on fists

This variation can be practiced in the event of various hand or wrist injuries as a substitute for normal handstand, which may then not be possible. However, this variation lacks the important ability to hold the shoulders away from the wall using the strength of the palmar flexors of the wrist, which requires a clean technique in which the torso swings up around arms that are held still.

Effects:

(428) Tone of the finger extensors

Instructions

- Place your fists instead of your palms with your palms facing each other.

- Keep your arms as still as possible during the upswing.

Details

- In contrast to normal handstand upswing, the body weight does not rest on the palms but on the fists, i.e. on the base joints of the fingers and the proximal interphalangeal joints. This can result in quite a lot of pressure being felt, especially on the base joints of the fingers. The more important difference, however, is that the palmar flexors of the wrist in the forearm can – and must – hold the shoulder area away from the wall in normal handstand upswing. These are no longer available for this purpose in this variation. It is therefore important to learn handstand upswing so well that the arms remain very still, i.e. the whole body swings upwards in the shoulder joint without the arms moving much and, in particular, without the shoulder area moving towards the wall, see also the variant do not move your arms. It is not a bad idea to have a supporter at your side for the first few attempts, who can support your shoulder in case of doubt.

- Keep your thumbs on the outside of your fist, never on the inside! Bend all finger joints with a certain maximum force, the fists must be compact and resilient!

- Due to the stretched wrist, the handstand on fists is the only variation that can still be performed with some hand injuries, apart from the more advanced handstand on fingertips.

- In this variation, the forearm muscles must keep the wrist stable and immobile. Don’t just press your fists aggressively against the floor, but also tense the forearm muscles responsible for flexing the wrist in dorsal direction (dorsiflexors) and in palmar direction (palmar flexors) to keep the wrist stable and immobile.

- Due to a slightly different rotation of the upper arm in the shoulder joint compared to normal handstand and because of the stretched wrist and the palmar flexors in the forearm that are not working on the edge of strength and flexibility, this variation can feel lighter in terms of arms and shoulder.

- While you can play and experiment with the parameter „pushing the hands away from / towards each other“ in a normal handstand, this would lead to a loss of stability in the wrist and, in extreme cases, to a twisted wrist, probably with serious consequences. Refrain from such experiments here.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Pressure on the knuckles Pressure on the „knuckles“, i.e. in particular the metacarpophalangeal joints, but also on the proximal finger joints, is subjectively perceived very differently, sometimes as hardly bearable. A much softer pad is helpful here, but it must not shift. A mat folded several times or patches on a mat should be ideal.

on fingertips

Strengthening the finger flexors

Effects:

(422) Strengthening the finger flexors

Instructions

- Place the fingertips with the fingers stretched out, the fingers form a semicircle with the thumb, the hands are turned out 15 – 20°.

- Keep your fingers powerfully extended, put maximum weight on your fingers and come into handstand without moving your arms significantly.

Details

- Before this variation can be practiced, the fingers must be strong enough and have proven themselves in comparable but simpler poses. This can be assessed as follows in terms of increasing difficulty and also increased in the following sequence:

- Downface dog: is possible for many, as only about half of the body weight rests on the fingers here, i.e. a quarter on each hand

- Upface dog: should definitely be performed from the downface dog. During the transition, slowly shift the weight further onto the fingers and assess whether upface dog will be possible. Often the doubt is greater than the lack of strength. The finger flexors are often felt intensely shortly after the pose.

- Staff position: the center of gravity is further forward here than in upface dog.

- Rectangular handstand, tolasana: in both poses, the entire body weight already rests on both hands, tolasana also requires a little balancing, so dynamic forces occur in addition to the static forces. Rectangular handstand is less difficult as it can be performed slowly and carefully. Of course, taking a jump is more challenging.

- Ardha vasisthasana, vasisthasana: in these poses, slightly more than half of the body weight rests on one hand.

- Handstand: just like in the right-angled handstand, only half the body weight rests on each hand, but the dynamic forces that occur during the upswing can require more strength and resilience.

- The finger joints are pushed into hyperextension by the body weight, forcefully push the fingertips towards the thumb, which is an exertion of force in all finger joints in the direction of flexion to minimize the effect of the forces that want to hyperextend the fingers.

- The upswing required for this variant resembles an exclusive rotation of the body in the shoulder joints (i.e. around the line connecting the two glenohumeral joints).

- The more steep you position your fingers and palm , the lower the hyperextensive moments in the finger joints. Use your finger flexors to resist hyperextension to the best of your ability.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Intense sensation in the fingers after leaving the posture: This pose represents a very unusual, great effort for the fingers. Accordingly, an intense sensation in the fingers can occur not only during the pose but also afterwards.

Temporary restriction of fine motor skills: Musicians in particular, but perhaps also precision mechanics such as watchmakers, may experience a temporary restriction of their fine motor skills, which is why it is recommended not to perform this variant the day before a concert, for example.

Upswing without rotating leg

Instructions

- Swing into a handstand without turning the swinging leg out or turning the pelvis sideways away from the jumping leg (the standing leg during swinging).

Details

- This variation can of course also be practiced well with a supporter who keeps a close eye on the leg and pelvis.

- Due to its inertia and the restricted flexibility of the hip flexors, the swinging leg tends to turn the pelvis sideways away from the trailing (jumping) leg. This is all the more true the more restricted the flexibility of the hip flexors is and the more momentum has to be used because there is not enough jumping power available. This effect should be reduced further and further, not least because the momentum of the leg is transmitted via the upper body to the shoulders and arms, causing unequal strain and demands on the shoulder joints and arms.

baddha konasana

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Place your bottom on the wall and keep your glutes slightly engaged to avoid falling into a hollow back.

- Bend the knees, pull the feet towards the pelvis and fold the legs from the hip joints towards the horizontal, i.e. into turned out abduction, and bend the thighs at the hip joints until the outer edges of the feet are horizontal and the legs are in the baddha konasana position.

Details

- With turned out thighs, move the feet on the wall towards the pelvis and the knees towards the wall so that the gravity perpendicular remains sufficiently favorable and you do not fall out of the pose towards the floor. If the knee joints are bent further, the knees will move slightly further away from the wall because the bending of the knee joints when the feet are placed on top of each other also causes the hip joints to flex with further abduction of the legs, since the adductors have a hip-flexing effect. This effect naturally has a detrimental effect on the gravity perpendicular.

- If the knees are actively bent with force for too long in order to pull the feet towards the pelvis, a cramp could occur in the hamstrings.

- Work against the hollow back with your abdominal muscles; in this pose your bottom moves upwards, away from your lower back.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Baddha konasana-typical knee problems that can occur if the knee joints are not fully intact. As is usual in baddha konasana, pain can also occur in the knee joint if the knee is not fully intact. A smaller bending angle often solves this.

Cramp in the back of the thigh: When the heels are pulled forcefully towards the pelvis, the hamstrings may tend to cramp, especially if this is actively attempted for a longer period of time. Let the gravity of the lower legs largely bend the knees and only briefly give an impulse to bend the knees further.

supta baddha konasana

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Place your buttocks on the wall, keep your gluteal muscles and, if necessary, your abdominal muscles slightly engaged to avoid falling into a hollow back. This effect naturally depends on the distance of the hands from the wall. Reduced mobility, particularly of the shoulder joints, makes a smaller distance necessary and increases this effect.

- Turn the thighs out in the hip joints, place the outer edges of the feet on the wall with the soles of the feet on top of each other, bend the hip joints and pull the feet towards the pelvis until the legs are in a supta baddha konasana position. The feet remain on the wall. Pull your knees as close to the wall as possible.

Details

- Move your knees towards the wall so that the gravity perpendicular remains sufficiently favorable and you do not fall out of the position towards the floor.

- Use the strength of your abdominal muscles to move your bottom up the wall so that you do not fall into a hollow back. If you press the outer edges of your feet onto the wall with moderate force, you can also use your glutes, which is the superior method as this does not affect your inhalation.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Baddha konasana-typical knee problems that can occur if the knee joints are not fully intact: As is usual in baddha konasana, pain in the knee can also occur here if the knee is not fully intact. A smaller bending angle often solves this.

Cramp in the glutes: When the knees are pulled forcefully towards the wall for long periods of time, the glutes may cramp, which may persist even after the pose. You can then try to remedy this with poses such as half lotus forward bend, hip opener at the edge of the mat, hip opener 3.

two-legged upswing

Instructions

- Place your hands shoulder-width apart with your fingertips approx. 20 cm from the wall and the tendons of your middle fingers pointing parallel to the wall.

- With the knee joints bent, place the feet at a significantly smaller distance than in downface dog, also parallel (with regard to the center lines of the feet) and pointing towards the wall.

- Press your palms firmly to the floor, give them maximum weight, straighten your arms well, keep your shoulders away from the wall and jump with all the necessary bounce in your legs.

- As your legs fly up towards the wall, straighten your legs and land gently with your heels on the wall.

- Check all parameters of handstand.

Details

- The optimum distance of the feet from the wall depends not least on the flexibility of the hamstrings and the glutes as well as the available power for jumping (bounce): the greater the bounce, the greater the distance can be, the lower the flexibility, the greater the distance must be.

- Even more so than the normal handstand upswing, this requires a great explosion of power for jumping, which requires a completely clear mind. Quite a few people have sort of a „mind issue“ during normal handstand upswing, and this is no less the case here. In contrast to normal upswing, where momentum can be gained a few times with the swinging leg before it is supplemented with the jumping leg for sufficient energy development, these times and processes coincide here, which requires concentration of energy and will. It is normal if this variation does not succeed over a longer period of time. It can be helpful to bounce slightly on the knees several times, although this is very far from the physical energy development of the swinging leg in normal upswing. In order to simplify the upswing, the elbows are often bent by a few degrees so that the potential energy that has to be achieved from the jumping power of the legs becomes affordable, and only then can the rest of the potential energy be added by stretching the elbows from the deltoids and triceps. As long as this flexion in the elbows remains controlled and the flexion angle does not become so large that stretching is no longer possible or only possible to a limited extent, there is nothing to be said against this aid. Another method that has proven to be effective is to first take handstand swinging normally with one leg, then land with two knees bent wide and immediately jump off again with full force without delay and without delaying mental processes. The bending knees absorb a lot of the potential energy from the landing and bend widely so that they can cover a large angular range during the subsequent stretch. The longer the force of the thighs has time to accelerate the body mass, the greater the energy used and the greater the height that can be achieved! This is all the more important as the available jumping power is usually quite limited. This procedure naturally requires healthy knee joints; disorders such as jumper’s knee, Osgood Schlatter’s disease in young people, gonarthrosis or meniscus damage are of course contraindications.

- In all cases, controlling the movement of the shoulder area is an essential requirement: it must not move uncontrollably towards the wall! The movement of the shoulders during the upswing has to be away from the wall, which makes the upswing more difficult and complicated. For your own safety, never violate this requirement. Practicing normal handstand upswing without moving the arms as described above, i.e. turning the whole body with the shoulder joint remaining in the same position and jumping around on the wall in a rectangular handstand, can prove helpful.

- Meaningful assistance from a supporter as in a normal upswing is much more difficult here, as both legs would have to be gripped. This means that the arm gripping the legs has to be pushed further forward by the supporter (from the supporter’s perspective) and the head is more likely to collide with one of the swinging legs.

- It takes some experience to find the right point at which to start stretching the swinging legs and the right speed of stretching. If the legs are stretched too early or too quickly, this may stifle the upswing, if they are stretched too late or too slowly, the heels may hit the wall roughly or even the buttocks may come into contact with the wall and, in the worst case, the shoulder area.

- It can be helpful to internalize the differentiation that although the pelvis jumps towards the wall and upwards, the shoulder area jumps less; its movement towards the wall is incomparably smaller and must remain very limited.

- In contrast to the normal upswing, this variation can be practiced better with injuries to the hamstrings (especially strains, irritations of the origin at the ischial tuberosity, the PHT), as the bounce hardly comes from the back of the leg, which is also not stretched at the beginning as with the swing leg of the normal upswing. This variation places far greater demands on the performance of the quadriceps and knee health, but less on the hamstrings.

Do not move your arms

Controlling the movement of the shoulder during the upswing

Instructions

- Jump into a one-legged handstand as described above, but try not to move your arms.

Details

- The shoulder often moves towards the wall during the handstand upswing. This movement must be controlled and limited for several reasons:

- the shoulders must not hit the wall, as this could trigger a shock and uncontrolled bending of the arms, which in most cases is no longer controllable due to a lack of strength, so that the end result could be an uncontrolled, rough landing of the head on the floor with a risk to the cervical spine.

- Even if the shoulders reach the wall with the arms stretched (and not uncontrollably bent), depending on the distance of the hands from the wall, many performers no longer have the strength to release the shoulders from the wall and assume the correct handstand.

- Wrist joints could be forced into dorsiflexion beyond their range of motion, and the resulting pain could be so irritating that it distracts from the necessary corrective movement.

- Even if the shoulders reach the wall with the arms stretched (and not uncontrollably bent), depending on the distance of the hands from the wall, many performers no longer have the strength to release the shoulders from the wall and assume the correct handstand.

- the shoulders must not hit the wall, as this could trigger a shock and uncontrolled bending of the arms, which in most cases is no longer controllable due to a lack of strength, so that the end result could be an uncontrolled, rough landing of the head on the floor with a risk to the cervical spine.

- This variation is intended to give you a better feel for the movement and control of the shoulder. In general, the upswing with shoulder control is perceived as more difficult than without; moving the shoulder away from the wall contradicts the body’s natural kinetics and requires more and more concentrated effort. It has often been observed that performers who are asked not to move their shoulders towards the wall, or to move them less towards the wall, are initially unable to perform the handstand lift with this requirement.

two-legged upswing as jumping

Instructions

- Do the handstand jumping on both legs as described above.

- As soon as you are in handstand, jump back to the floor on both legs, dip your knees and jump off again immediately without delay and without thinking about it.

- Repeat this for as long as your stamina allows or until you lose control, which could lead to danger.

Details

- As already described in the two-legged lift, this is not accessible to everyone. The trick described there of landing on both legs after a one-legged upswing, landing low on the knees and immediately jumping off again without delay or hesitant thinking, usually with full jumping power, becomes a jumping movement that can be repeated at will. Getting into the flow in this way can make it easier to get up on both legs, firstly because the movement becomes more conscious and the parameters and dependencies are better known and felt, and secondly because the psychological blockages that often lead to insufficiently powerful jumping in the sense of subconscious or partially conscious avoidance behavior become smaller, not least because of the successful action and confirmation, but also because of the extraordinary focus required.

- If your strength/endurance or control decreases, stop!

- Here the dependence of the time at which the stretching of the legs is started, its speed and the resulting force with which the heels hit the wall (if at all) can be well investigated and it becomes clear that too early a start or too great a speed of the stretching leads to a slowing down or even to the termination of the upswing movement, the reason is of course the swing energy consuming increased lever arm of the center of gravity of the accelerated body mass.

- Most thought processes that are not proactively closely linked to movement and the evaluation thereof are extremely obstructive here.

Dips

Effects: (302) Triceps strength

Instructions

- Take a handstand, jumping off with one or two legs.

- Slowly bend your elbows outwards to the limit of your strength, but not more than approx. 120°, even if you have a lot of strength in your arms.

- Slowly extend your elbows again in a controlled manner and then bend them again, stretch them and so on…

Details

- Excessive bending in the elbow joints puts undue strain on them as well as on the ulnar side of the wrist. Even if, which is rather rare, there is enough strength available to bend the arms significantly more than 90° (and extend them again), approx. 120° should be the upper limit for bending.

- If there is little strength available in the arms and shoulders, this variation may start with a few degrees, as is also known from the pole position. Younger women in particular often have less arm strength, statistically speaking and due to their average movement patterns, and need to build this up slowly.

- If there is significant discomfort in the ulnar sides of the wrists, the angle of the hands to each other can be varied, in particular the hands can be turned in a little. It is also quite helpful to increase the distance between the hands.

eka pada

Effects: (721) Stretching of the hamstrings

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- Slowly move one leg further and further away from the wall towards the floor until you reach the limit of the hamstrings’s flexibility.

Details

- When moving the leg towards the floor, depending on the exact position of the pelvis, the shoulder and the distance from the wall, there is a point of no return at which you will inevitably fall out of the pose because the gravity perpendicular is beyond the wrists when viewed from the wall. You can feel how far you are from this point by the weight with which the remaining heel presses on the wall. If the distance between your hands and the wall is not too great, it is important to shift body mass towards the wall, i.e. to move your shoulders or pelvis or both towards the wall. As already described above, the movement of the shoulders towards the wall should be treated with great respect, because for almost everyone there comes a point at which the strength of the deltoids is no longer sufficient to move the shoulders away from the wall back to the starting position. Care must therefore be taken when moving the shoulders. The movement of the pelvis towards the wall is far less critical. If the leg has been lowered a little, it is often enough to release the tension in the abdominal muscles. If the pelvis is moved towards the wall without having already bent one leg in the hip joint, an uncomfortable hollow back can naturally occur. Sequence and measure are therefore not unimportant here. Move the leg away from the wall towards the floor in such a way that you can feel sufficient pressure from the heel on the wall at all times by moving the pelvis and, if necessary, the shoulder. If the leg is moved very quickly from the flexed hip joint position back up to the wall, the heel of the upper leg may briefly leave the wall despite the other parameters being correct. However, this does not indicate that the gravity perpendicular, i.e. the position of the pelvis and shoulder in relation to the distance of the hands from the wall, is not suitable, but is a kinetic phenomenon due to the inertia of the leg to be lifted, which would not occur statically or very slowly in the same position of the leg and disappears again when the leg is lifted further. Even if, towards the end of the movement, the gravity perpendicular was still slightly unfavorable, the inertia of the already accelerated leg would move the pelvis and possibly the upper body a little towards the wall. Another reason not to accelerate the leg to be lifted too much is the limit of the hamstrings at the ischial tuberosity: if the leg is accelerated with the full muscular capacity of the hamstrings, there is not only a risk of the above-mentioned tipping over but maybe over time also of overloading its tendinous origin with strain or PHT, Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy.

- As already described in the last point, the distance between the hands and the wall must not be too small, because otherwise the gravity perpendicular would be beyond the wrists when the leg is lowered as far as possible, meaning that the pose could no longer be maintained from a purely physical point of view.

- The gravitational force of the lowered leg creates a moment in the respective hip joint, which tilts the pelvis in such a way that the lumbar spine is moved in a convex (kyphotic) direction (in relation to the other leg in direction of extension in the hip joint) and continues through the back into the shoulder joints in the sense reducing frontal adduction, i.e. the opposite of the maximum frontal abduction to be performed. Consequently, lowering the leg will increase the work required in the shoulders and arms so that the shoulder joints remain extended (in the sagittal plane) and do not move towards the wall. At the same time, the lowered leg largely protects against an uncomfortable hollow back due to the moment created in the hip joint and the resulting tendency to straighten (in direction of convex) the lumbar spine.

- The lowered leg tilts the pelvis as described above and moves the contralateral hip joint into extension or at least in the direction of extension in the hip joint. This in turn leads to evasive movements of the leg in the respective hip joint at the limit of flexibility with regard to extension in the hip joint, in which it tends to turn out and the pelvis may take a slightly inclined position in the frontal plane. In addition, the knee joint of the upper leg wants to bend and the pressure of the heel on the wall is reduced.

- Extend the lowered leg and avoid to turn it out.

- As the knee of the lowered leg approaches the flexibility limit of its hamstrings, it shows an increasing tendency to bend, which is not compensated for by the gravity of the lower leg, which contributes to stretchint the knee in the direction of extension according to the design of the pose. An extended knee joint can therefore generally only be achieved by using the quadriceps when the leg is lowered far. The tendency of the rectus femoris to cramp, which is very common when the knee is extended while the hip joint is flexed, is significantly less than in poses in which the knee has to be extended against gravity.

free

Instructions

- ..

Details

- ..

Hands on the wall

Instructions

- Place your hands so close to the wall that the first fingertips (usually the middle fingers) touch the wall.

- Take handstand one-legged.

Details

- This variation requires a lot of fine-tuning so that the body does not fall out of handstand again. The relationship between the individual components of the upswing must be just right. If the swing is too big, you will „bounce“ off the wall again. If, on the other hand, it is too small, the pose will not be achieved. The relationship between the individual components of the movement must also be precisely coordinated.

- The pressure usually exerted on the wall with the heels will only be minimal here.

Hands turned inwards

Instructions

- Place your hands with the wrists shoulder-width apart approx. 20 cm in front of the wall so that the tendons of your middle fingers are pointing towards each other, i.e. turned inwards.

- Take the pose as described above (one-legged upswing).

Details

- In this variation, as with hands turned outwards or backwards (away from the wall), the strength of the palmar flexors, which help to limit or intercept the movement of the shoulder towards the wall, is missing. This variation is therefore not suitable for inexperienced beginners. The only rather weak substitute available is the increased supination of the forearm/wrist, which is significantly weaker in terms of muscles, but also due to the smaller lever arm (half the width of the hand compared to the length of the palm). Experience and mindfulness are therefore required to prevent the shoulders from moving significantly towards the wall, which can no longer be intercepted from a certain, relatively early point.

- The changed position of the hands results in a different effect on the shoulder and forearm muscles. If the hands were placed too far apart, the stretching requirement in the wrist in terms of dorsiflexion would increase to an unmanageable degree. Even before this, compression pain in the dorsal wrist area is likely to occur, which can hardly be controlled even with vigorous use of the palmar flexors of the forearm. In addition, depending on the flexibility, a clear to excessive stretching sensation of the palmar flexors may occur. On the other hand, it is not advisable to keep the hands too close together as this would result in a loss of lateral stability, which is particularly true for beginners with an insecure and not very powerful upswing, see the discussion above (inertia of the upper body and gyroscopic forces).

- If the body threatens to tip to the right, the right arm must be pressed more firmly against the floor for a short time, and the left arm can also be bent slightly for a short time.

Hands turned outwards

This variation allows you to feel the stretch in the inner arm area better and gives you a little more feeling for free standing than normal handstand.

Instructions

- Place your hands facing outwards, about shoulder-width apart, not narrower, and swing into handstand.

Details

- If the distance between the hands is too narrow, the width of the physical support base is reduced, making it more susceptible to lateral wobbling. This is not normally a problem in handstand, but it may be a problem for performers who do not apply much momentum when taking up handstand, as the upward swing of the leg and the upward swing itself, due to their asymmetry and dynamics, involve the need to balance torques around the body’s longitudinal axis and rotational moments. The lower the speed of the up-swinging leg, and subsequently the pelvis and upper body, with which they move into the pose, the more force and attention must be applied to compensate for these moments, see again the discussion above (inertia of the upper body and gyroscopic forces).

- As already described elsewhere, there is no possibility of using the palmar flexors of the wrist to keep the shoulder away from the wall, which is very important for taking handstand, especially for the inexperienced. It follows that this is not a variation for the less experienced. You need to have a confident command of the upswing in order to practise this variation safely. A gradual approach to the 90° rotated position is recommended, e.g. by rotating the hands 10° – 20° further in a quick sequence compared to the normal position and not holding the handstand for long, so that the change caused by the rotation can be perceived and evaluated in a close temporal context.

- If pain occurs in the dorsal wrist, the distance between the hands can be increased slightly.

- This variation feels a little „freer“ and looser in the shoulders and arms; however, this must not lead to a loss of care. There is a certain risk of hanging in one of the two shoulders. Instead, stretch upwards evenly and powerfully from both shoulders.

Hands turned backwards

This variation is very different from normal handstand. Here, the tendency of the shoulder to move towards the wall while swinging up into the handstand is very pronounced, which requires careful approach through various harmless angles of turning out the hands. This pose should not be practiced at all for a long time by beginners and should definitely be practiced under the supervision of an experienced teacher by more advanced students. In addition, the flexibility requirements of the shoulder and forearm muscles are pronounced.

Instructions

- Place your hands on the floor facing away from the wall, the tendons of your middle fingers parallel. Be sure to keep the shoulder moving away from the wall, as it will want to move towards the wall during the upswing, which is very difficult to control here.

- Take handstand.

Details

- Approach the 180 degree turn of the arms step by step. Observe the tendency to be able to control the shoulder less easily (in terms of evading the wall) with each additional step.

- A typical (and initially justified) protective measure taken by many people who are not practiced in this pose is to try to make the impact of the first heel on the wall more gentle by bending the leg a little. This is justified and sensible to the extent that the body wants to move further towards the wall after the first heel touches down due to inertia. The harder the stop, the more pronounced the effect of the inertia will be and the more the upper body will move towards the wall. There is no way of counteracting this in the forearms/hands; this has to be done solely from the strength of the shoulders and a clever choice of the gravity perpendicular just in front of the wrists (on the finger side), which is generally a very unusual requirement that also may take place at the limit of shoulder flexibility and dorsiflexion: The more favorably you try to hold the gravity perpendicular (i.e. further away from the wall), the greater the dorsiflexion required, especially in the upswing. It follows that this variation should not be practiced without sufficient dorsiflexion of the wrist that can significantly exceed 90° under load.

- The necessary and correct effort to keep the shoulder away from the wall leads to the upswing becoming somewhat more difficult, i.e. requiring more momentum.

- Bending the elbow joints slightly at the beginning of the swing up can make it easier to control the shoulders. Of course, this must remain controlled. It should be noted that the slight bending of the elbow joints in the direction of dorsiflexion beyond 90° places even greater demands on the flexibility and strength of the wrists, i.e. the forearm muscles, than the sole attempt described above to hold the gravity perpendicular in a favorable position.

- Ideally, the arms should be completely still during the upswing. It makes sense to practise this in advance with the normal hand position, see above.

Push hands towards each other

The purpose of this variant is to get more feeling for stretching upwards. It also involves the pectoralis major working in the pose and reduces the tendency to hyperextend the elbow joints.

Instructions

- Take handstand the normal way and make sure that your hands are no more than shoulder-width apart.

- Start to push your hands towards each other against the resistance of the floor.

Details

- Avoid reducing the angle of frontal abduction in the shoulder joints from the required 180° in order to have more strength for pushing the hands towards each other, which is equivalent to a partial shift of the load from the weaker anterior deltoid (pars clavicularis) towards the stronger pectoralis major muscle. For several reasons, the upper arms are often moved slightly outwards when the elbow joints are flexed, which also provides significant relief:

- The load arm from the glenohumeral joint to the place where the force acts (the floor) becomes shorter, so the available force can act more favorably.

- The working points of both the deltoid and the pectoralis major are shifted to a more favorable range according to the force-length function.

- As well as pushing your hands towards each other, stretch as far as possible from your shoulders (elevate the shoulderblade). This is a good preliminary exercise for free standing in handstand.

- Those who hyperextend the elbow joints have another good option for reducing or preventing hyperextension in addition to the pure use of the biceps described in the FAQ: vigorously pushing the hands towards each other is unlikely to be compatible with hyperextension, as the biceps (more precisely: its adducting caput breve; caput longum belongs to the abductors due to its course lateral to the glenohumeral joint) is almost inevitably also used. Rather, care must be taken to ensure that the arms do not bend significantly here, especially in less flexible shoulder joints where this inclination is present anyway.

- Pushing the hands towards each other tends to reduce the external rotation of the arms by using the internally rotating anterior deltoids and the pectoralis major. Ensure that this is maintained as fully as possible.

Known problems that can occur even when executed correctly

Tendency to cramp

A tendency to cramp can occur in the anterior shoulder muscles pars clavicularis of the deltoids or the pectoralis major.

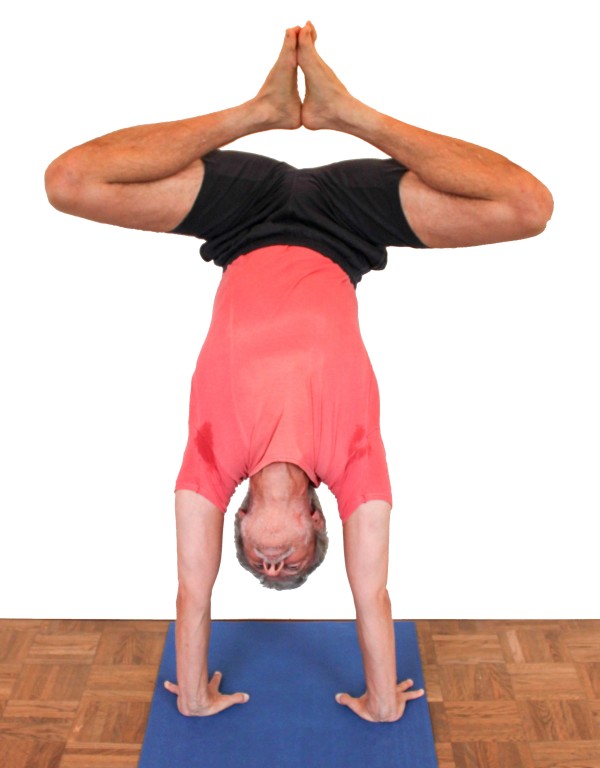

Head and back against the wall

Instructions

- Place your hands on the floor a short distance from the wall, palms facing the wall as usual, fingers slightly apart.

- Swing into handstand.

- Slowly place your bottom on the wall, keeping your shoulder away from the wall for the first step.

- When your bottom is resting on the wall, carefully and slowly start to move your back and shoulders towards the wall until they finally rest on the wall.

- Check the work of the arms again and push the upper body upwards on the wall against the existing friction (from the force of the shoulder blade elevators).

- To exit this variation, go back the same way: first release your shoulders from the wall, then your back and bottom (not the other way round!) and then come out of handstand.

Details

- Warning: this variant is completely unsuitable for beginners! It requires experience, strength and control!

- This variation requires a great deal of strength in the arms and shoulders, especially if the distance between the hands and the wall is not exactly small, just a few centimeters can make a big difference!

- Less experienced users in particular should start with a very small distance between their hands and the wall. There is a conflict of goals here: if the hands are directly on the wall, it is very difficult for the inexperienced not to fall straight back out of handstand; if it is too large, the strength of the deltoids (and the upper back) will not be sufficient to slowly place the shoulder on the wall in a controlled manner, much less to release it from the wall again later in a controlled manner.

- If at any point during this variation you feel a lack of strength in your arms or feel that you can no longer release your shoulders from the wall, pull one leg out of the pose towards the floor, which will immediately relieve the strain on your arms and allow you to exit handstand in an orderly and safe manner.

- The wrists are well over 90° dorsiflexed here! Depending on the selected distance and flexibility of the forearm muscles (palmar flexors and finger flexors), a clear discomfort can occur in the dorsal side of the wrist. This is a sensation that does not indicate anything constructive such as stretching or strengthening, but simply compression of non-muscular structures of the joint, which must be avoided. If more forceful use of the palmar flexors is not sufficient, build up the pose again with the hands at a smaller distance from the wall.

- The buttocks are placed on the wall by gradually reducing the tension in the abdominal muscles and, if necessary, using the strength of the autochthonous back muscles to bend the lower back slightly backwards. To raise the shoulders, this slight backbend must be released again and the angle of frontal abduction in the shoulder joints must be reduced. This combination is not known from other poses and is more likely to occur when exiting poses such as back arch. If the shoulder area is placed on the wall, the force required increases the closer the shoulders are to the wall. The maximum required force of the deltoid increases significantly with the distance of the hands from the wall. Similarly, the required flexibility in the direction of dorsiflexion of the wrist increases. Both values quickly exceed any reasonable level!

- Keep your arms stretched consistently, even and especially when it gets strenuous!

- If your hip flexors are clearly restricted, your heels may lift off the wall if you place your back and shoulders on the wall after having placed the bottom on the wall. This is not fundamentally problematic, but it does take away some of the feeling of security in the pose and costs lateral stability! From a diagnostic point of view, a clear restriction of flexibility in the hip flexors is made visible in this way.

- If this variant is successful and the forces occurring can be assessed, the head can also be removed from the wall.

- The neck muscles that move the head should not be subjected to too much strain; in cases of known damage to the cervical spine, this variant may be contraindicated.

stand with your feet on the wall

Demands and gives more sense of balance

Instructions

- Assume the handstand position and choose a distance between your hands and the wall that is slightly longer than the length of your lower leg.

- Place one foot after the other with the sole on the wall so that the lower legs are horizontal. The whole body moves from the initial incline of normal handstand to the vertical.

Details