yogabook / movement physiology / bone

Bones are the tensile and compressive components of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. Accessory bones are located outside the musculoskeletal system, such as the ossicles. The bones of the musculoskeletal system belong to its passive part. Bones can have a protective function, such as the ribs (for the heart and lungs) or the skull for the brain. Erythrocytes (red blood cells), leukocytes (white blood cells) and thrombocytes (blood platelets) are formed in the parts of the bones containing red bone marrow. Bones can vary greatly in length and shape, see e.g. femur, sesamoid bones and scapula.

Bones are divided into

- long bones (Long bone), z.B. die langen Knochen der Extremitäten wie Femur, Tibia, Fibula, Forearm, Radius, Ulna). Diese bestehen aus einem Knochenschaft (diaphysis) zwischen zwei epiphyses (Wachstumszonen), hinter denen die metaphysis liegen, häufig mit Condylen oder Tuberkeln.

- flat bone (Flat bones) wie Shoulder blade, breastbone, die Knochen des Beckens (ischial tuberosity, iliac bone, pubic bone), ribs, skull bone

- short bones (Short bones) ohne besondere Form wie sie als carpal bones und tarsal bone vorkommen

- sesame bones (Sesamoid bones), dazu wird auch die Patella gezählt

- irregular bones such as the vertebrae and the lower jawbone (mandible)

- Some bones (Ossa pneumatica) are not classified as flat bones despite their shape, as they surround cavities lined with mucous membrane, such as the frontal bone.

Bones are living organs with a good blood supply. They are usually surrounded by periosteum on the outside, except in areas where they articulate with other bones, where they are covered with hyaline cartilage. Underneath the periosteum lies the cortical bone, which is very dense and solid in the diaphysis of long bones and is therefore referred to as compact bone. Deeper than the corticalis/compacta lies the spongy spongiosa, which is spongy in structure but not in consistency. It is a framework of fine bone beams (trabeculae) that mainly determines the stability of the bone by absorbing tensile and compressive forces according to their orientation.

Inside the spongiosa is the medullary cavity, a space filled with bone marrow. In many bones, the bone marrow is converted into yellow fatty marrow over the course of a lifetime; only in some bones does the blood cell-forming (haematopoiesis) red marrow remain: ribs, sternum, vertebral bodies, hand and tarsal bones, flat skull bones and the bones of the hip bone.

In addition to 25% water, bone consists of 45% inorganic material and 30% organic material, 95% of which is type 1 collagen.

Bones can withstand a greater degree of tensile and compressive stress, and to a certain extent they are also flexible. The bending stresses are partly absorbed by tensile straps consisting of ligaments, muscles and fasciae, the best known of which is the iliotibial tract as a tension band for the femur. If the tendon fails or is damaged, spontaneous fractures can occur.

Contents

- 1 Modelling und Remoddeling

- 2 bone adaptation

- 3 osteoanabolic

- 4 Condylus

- 5 Epicondyle

- 6 Tubercle

- 7 apophysis

- 8 diaphysis

- 9 Epiphysis / Epiphysis ossis

- 10 Epiphyseal plate / growth plate

- 11 metaphysis

- 12 Periosteum

- 13 Cancellous bone

- 14 Corticalis

- 15 long bones

- 16 Trabeculum

- 17 bone marrow

- 18 Medullary cavity/medullary chamber

- 19 osteoclasts

- 20 osteoblasts

- 21 osteocytes

- 22 Callus

- 23 fracture healing

- 24 Osteolysis

- 25 traction apophysitis

- 26 Epiphysiolysis

- 27 aseptic bone necrosis

- 28 Exostosis

- 29 Osteophyte

Modelling und Remoddeling

In bones, remodelling refers to a balanced or negative net balance between bone formation and resorption; otherwise, the term modelling is used. Remodelling occurs as follows in units: Osteoclasts eat a superficial tunnel into the bone within about two weeks, called a Howship’s lacuna. When the pit is deep enough, they send signals to the osteocytes, which then differentiate into osteoblasts, migrate into the pit and proliferate. They build a skeleton of ground substance into the pit, which is then filled with collagen fibres. This process takes about 3 to 4 months. After that, minerals are deposited, which takes another six to twelve months. In the end, the osteoblast has completely integrated into the bone substance and becomes a dormant osteocyte again. This description applies to the cortical bone; the trabecular cancellous bone, which has a turnover rate that is about four times higher, is much faster. In bone, too, it is transmembrane proteins, the integrins, that transmit signals to the osteocytes. When mechanical stimuli are applied, fluid is transferred from the compressed or compressed side of the bone to the stretched side, resulting in a piezoelectric effect. Proteins, enzymes and the growth factor IGF also play a role in this process. If the bone is subjected to excessive stress, the osteoclasts remove destroyed cells and matrix molecules in order to initiate replacement. Modelling must be distinguished from remodelling: repeated excessive mechanical stimuli lead directly to osteoid synthesis of the superficial osteoblasts, resulting in an increase in bone diameter. Among prepubertal athletes, Turner et al. found that gymnasts had the highest bone density, while swimmers had normal bone density at best or even lower bone density, which can be explained by the lack of ground reaction forces. For cycling, walking and strength training, it can be said that low intensities lead to no or little adaptation. The situation is different for jumping disciplines and high-intensity strength training, for which osteoanabolic stimuli have been proven, so that young weightlifters, for example, have higher bone density. There is a roughly proportional increase in bone mass with muscle strength, but muscle mass also appears to correlate with bone mass. These two variables naturally diverge in older, inactive people because the lack of use of the muscles leads to intramuscular fat deposits, so that an apparently adequate muscle mass is offset by significantly lower strength. Similar results to those for younger people apply to later years of life. In a study of women aged 65 and over, half of the participants were unable to lift a weight of 5 kg, which indicates a significant reduction in muscle strength and muscle mass, which are known to predispose people to osteopenia. A correlation has also been proven between training intensity and bone mass. Studies involving training programmes have demonstrated increases in muscle strength of up to 174% within 8 weeks. This carries the risk that bones that are less robust at the outset and may also be osteoporotic will not be able to withstand the rapidly increasing muscle strength, as the increase in bone mass and resilience takes much longer than the increase in muscle strength. In strength training, it is assumed that 70% to 80% of 1RM is necessary as training intensity to maintain bone mass, which corresponds approximately to 10RM. Endurance exercises that maintain bone mass are primarily those with high ground reaction forces, such as running. The training volume proves to be much less important than the training intensity, as the marginal benefit decreases relatively quickly. If the training volume exceeds a certain level, there are negative effects on bone density, which decreases due to hormonal factors. In terms of training frequency, at least three sessions per week are desirable. The stimuli from mechanical stress are stored in the bone matrix for around 48 hours and continue to have an effect. It can now be said that vibration therapy and the presumed osteoanabolic stimuli from vibrations do not exceed the effect produced by muscular stress. Prolonged intensive static stimuli on the bone can reduce osteoid synthesis. Osteoanabolic stimuli are always regional, i.e. they relate to the area that is stressed and not to the entire bone. Even though there are only a few results showing an increase in bone mass of more than two to three per cent, the load-bearing capacity of the bone has improved by a quarter.

The prevalence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women is reported to be around 15% in the fifth and sixth decades of life, but rises to 45% in women over 70. In contrast, the figures for men are 2.4% and 17% respectively, which is significantly less than half. This means that postmenopausal women of advanced age have the highest risk of fracture. At the onset of puberty, the body is particularly receptive to osteoanabolic stimuli, allowing for an increase in bone mass and stability that is not possible in later years. This effect appears to be the result of a synergy between high osteoblast activity and high levels of growth hormones. The first five years of menopause appear to be particularly critical, with bone mass loss of up to 15% possible in individual cases. There is evidence that a certain increase in bone mass is possible at any age if appropriate training is completed. Primary and secondary causes are given for the general fracture risk. Apart from the initial phase of intensive strength training for those who were previously untrained, during which rapid increases in muscle strength can be achieved that the increase in bone mass and stability cannot keep up with, all available strength can be exploited at a later stage, as, especially with regular training, both increases are only delayed in the bones due to the time lag. Especially in the early stages, high movement speeds and jumping disciplines should therefore be avoided. For patients with questionable bone substance, fall prevention is of great importance, as 90% of hip fractures and 50% of spinal fractures result from a fall. Those affected often do not regain their original level of activity. Unfortunately, only 10% of those affected show a low level of adherence to institutionalised or self-administered training programmes.

bone adaptation

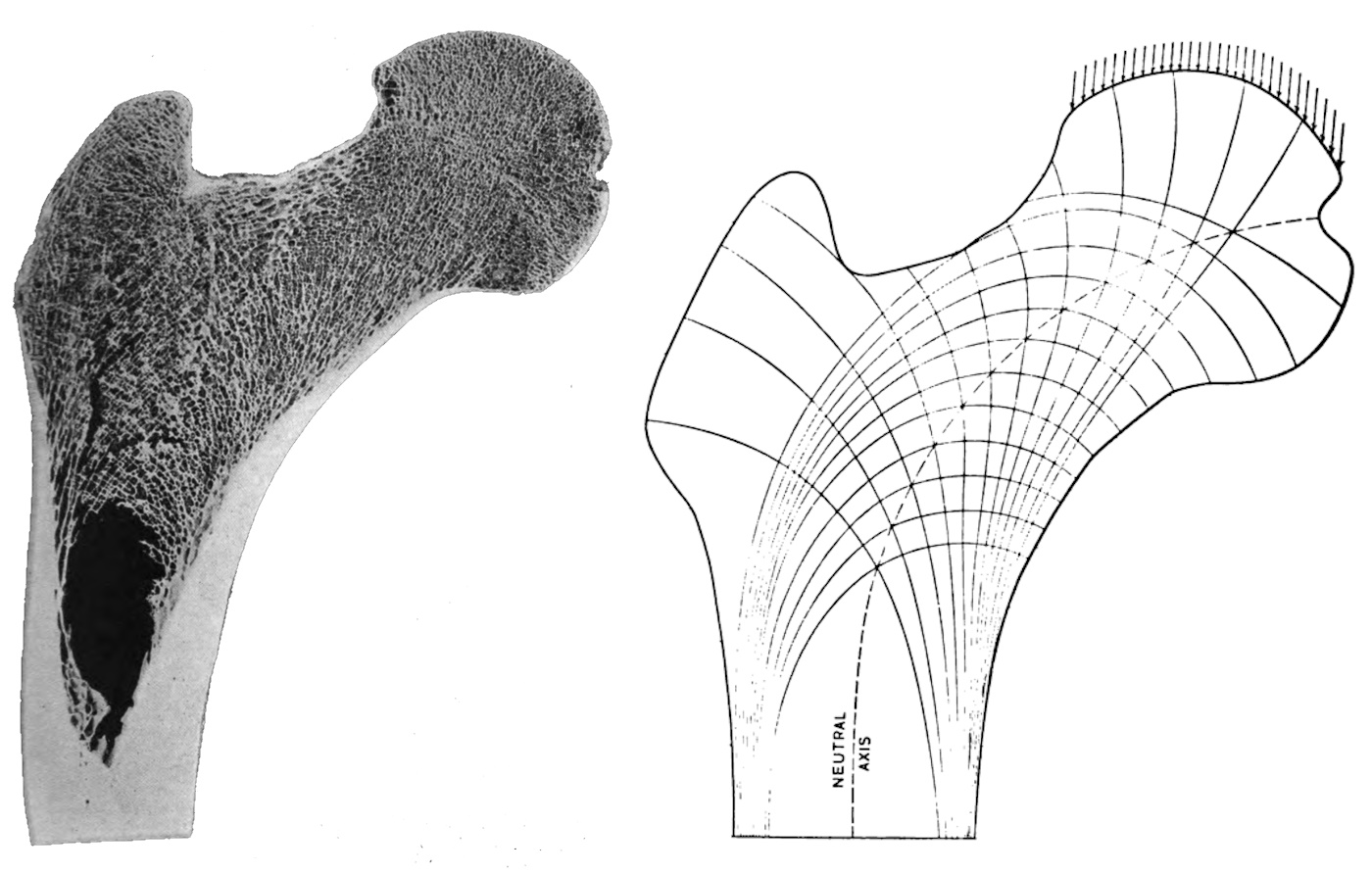

Experiments have shown that an unloaded bone in weightlessness loses 25% of its mass in the first 3 months and a further 25% of its original mass in the following 3 months. Consistent immobilisation, such as absolute bed rest, has a similarly devastating effect on the bone. Stress on the bone in the form of tension, pressure, torsion or bending are elementary stimuli for bone maintenance. Even medication cannot stop the bone mass loss that would otherwise occur. Torsion generates tension all around, while bending generates tension on the convex side and pressure on the concave side. Wolf (1892, Wolf’s Law) postulated that bones adapt to stress, i.e. they lose mass when stressed insufficiently and build mass when stressed excessively, increasing in density and strength. To this end, he examined, among other things, the trabecular structure of the proximal femur and found that it adapts to stress. In 1960, Frost postulated in the Utah Paradigm of Skeletal Physiology that bones adapt to daily stress throughout life by responding to maximum deformations. Bone deformation is measured in microstrain µS, with 1 strain corresponding to a 100% change in bone length, meaning that 1000 µS corresponds to a 0.1% shortening under compression or elongation under tension. Frost divides healthy bone into four stress zones and describes how the bone reacts in each zone:

- Disuse: the zone below 800 µS leads to a reduction in bone mass and strength.

- Adapted state: the zone of 800–1500 µS preserves the bone; remodelling and repair take place, but there is neither an increase nor a decrease in mass and strength.

- Overload: the zone above approximately 1500 µS to approximately 15000 µS leads to an increase in bone mass and strength.

- Fracture: loads above approximately 15,000 µS lead to fractures.

This makes Wolf and Frost among the founders of mechanobiology, which attempts to describe changes in biological conditions in response to mechanical stimuli, thereby distinguishing itself from biomechanics, which attempts to describe the behaviour of a system considered to be fixed. As a conceptual analogue to the technical thermostat, which regulates heat flow depending on the available heat, Frost spoke of a mechanostat that regulates load capacity depending on the load present. The typical maximum deformation of a tibia, as occurs in everyday life and sport, is around 2000 µS (humans) – 3000 µS (animal experiments) and thus a good half a ten power below the fracture threshold. Everyday stresses outside of sports and heavy physical work often remain within the range of only 10 µS, which is completely insufficient for bone maintenance. Stresses of 1000 µS and more are very rare. From deformations of around 4000 µS, the bone provisionally builds up mechanically inferior fibrous bone, which it then converts into stable lamellar bone. However, if it is repeatedly disturbed because the available regeneration time is too short, this can lead to fatigue fracture. The fracture limit of approximately 15,000 µS cannot be reached in healthy bone even with the most powerful explosive use of muscles; external forces are necessary for this.

The above considerations only apply to tension and compression, in which the tibia can withstand 50-60 times the body weight. However, the maximum bending load perpendicular to the longitudinal axis is ten times lower. Furthermore, the same values do not apply to all bones. The skull bone, for example, has a 6-8 times lower remodelling threshold, i.e. around 200–250 µS instead of 1500 µS, which means that it reacts much earlier to stimuli or necessities and thus provides greater safety through much faster adaptation. Only suprathreshold stimuli can be considered as bone mass-increasing stimuli. The level is the more important factor than the number: both parameters behave largely linearly up to the threshold of 4000 µS, but the function for the level of the stimuli is steeper than that for the number. This also results in weightlifters having on average 20%–30% higher bone mass than similarly well-trained marathon runners. Single high deformation loads do not have an osteoanabolic effect, only repeated ones do. This model refers only to the pure height and number of deformations. In reality, the acceleration during deformation is also relevant, so a faster deformation leads to a higher adaptation than a slower one of the same height. If the bone is accelerated at 1.1 g, this already has a positive effect on cortical thickness; at 2.5 g, the circumference of the bone increases; at 3.9 g, which can be achieved during fast running and in track and field disciplines, bone density also increases; and at 5.4 g, the cortical cross-section increases.

The hormone oestrogen appears to have an anti-osteoanabolic effect, as demonstrated in young, pre-pubescent female tennis players, whose bone mass increased more than that of players in puberty or beyond as a result of comparable training. Animal experiments (ovariectomised rats) also showed that administered oestrogen has an anti-osteoanabolic effect, but also inhibits bone resorption. It also lowers the threshold for minimum effective stress in the cortex and trabecular structure, but not in the periosteum. Male rats given oestrogen built up 43% less bone mass during osteoanabolic training. It is assumed that postmenopausal oestrogen deficiency leads to a reduced osteoanabolic effect of fundamentally osteoanabolic training stimuli. It has been shown that both sexes react differently to oestrogen administration: while the ER-alpha receptor was important for the osteoanabolic effect in female mice and the ER-beta receptor tended to inhibit it, the bone-building effect in male mice decreased with oestrogen administration.

Bone adaptation is based on a control loop in which osteocytes act as mechanosensors that activate osteoblasts and inhibit osteoclasts when necessary in the event of overload, continuing to do so until the osteocytes no longer detect overload. Together with the regular activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, this creates an adaptive dynamic equilibrium. The thickness of the accompanying musculature has proven to be a useful reference for the bending stresses to which a bone is regularly exposed, as the thickness represents a correlate to maximum strength that is suitable for everyday use, based on the muscle’s ability to adapt to stress by means of hypertrophy or atrophy. In the case of pathologically altered bones, such as in osteoporosis, the fracture threshold is sometimes significantly reduced and unknown. In this case, it is advisable to work with lower stimuli in order to minimise the risk of fracture, but with more repetitions. Vibration therapy has proven effective here.

In practice, a distinction must be made between movements that primarily generate gravity-induced axial pressure on the bones, as is the case with walking and running, and those that primarily generate bending moments from applied muscle force. In principle, both groups can have a sufficient osteoanabolic effect. Where the intensity is insufficient, this can often be compensated for by iteration. In the second group, strength training is characterised by its positive effects and a number of accompanying benefits, such as very effective strengthening of the muscles and their tendons, the release of myokines and (when performed correctly) very few side effects. The endurance sports of swimming and cycling provide hardly any axial loads and insufficient bending and torsional moments, so that studies have been unable to prove any osteoanabolic effect, in contrast to running (running). The dance and jumping disciplines in the first group also achieved a sufficient effect, but one must be cautious with recommendations due to the possible range of side effects and the associated probabilities in the area of the joints. For example, sufficient dance training can prove ruinous for the knee joints, while jumping disciplines often do not affect the joints but pose risks to the muscles (strains, tears) and tendons (insertion tendinopathies).

Studies indicate that walking has an impact equivalent to 1.5 times body weight, which is hardly sufficient as a maintenance stimulus. Running is significantly better at around 2.5 times body weight, but is not yet osteoanabolic enough to build bone mass or density.

Jumping, on the other hand, is scientifically proven to be osteoanabolic at about 4 times body weight,

although the exact level of stimulation naturally depends on the height of the jump and whether you land on one leg or two.

A few dozen jumps should be sufficient; a significantly higher number may cause side effects elsewhere.

Water gymnastics is likely to be effective due to repeated movement against water resistance, which increases in kinetics in the extremities with speed over the distance from the joint to the torso and can therefore lead to significant bending moments. However, depending on the movement, high training volumes can also lead to varus and valgus moments, which put strain on the menisci or collateral ligaments.

Tai chi is likely to be most effective in the lower extremities due to alternating movements with bent knee joints and the need for dynamic stabilisation of the stance. Here, too, it must be borne in mind that some movement sequences involve turning the body while standing on one foot with bent knee joints, which generates significant shear forces in the menisci. Non-axial flexion of the knee joints, i.e. flexion involving rotation in the knee joint during extension or flexion, can also be seen in Tai Chi.

However, all forms of training seem to have one thing in common: training once a week is just enough to maintain bone mass. For an osteoanabolic effect, training at least twice a week is necessary.

The strength of a bone results 60% from its bone mineral density and 40% from other factors such as cross-section, trabecular architecture, bone quality and the functionality of the osteocytes.

Compared to dry wood of the same diameter, the breaking load for bending is three times higher for bone and still half as high as for steel. Before humans reach full growth, bone growth is subject to a circadian rhythm, with the maximum occurring at night. For reasons that are not yet clear, this can cause growing pains. Growth takes place in the epiphyseal plates, which ossify at the end of the growth phase around the age of 18. The permanent remodelling of bone (including renewal) is referred to as bone tissue modelling.

Most bones develop from the hyaline cartilage skeleton (chondral ossification), only the skull bones develop from connective tissue precursors (desmal ossification).

osteoanabolic

Osteoanabolic refers to stimuli or substances that promote bone formation, see derivation above.

Condylus

Condyles, also known as joint processes or joint knobs, are the thickened areas at the ends of bones that contain the articulation surfaces with other bones.

Sometimes, the condyles are covered by epicondyles, which are bony protrusions to which muscles or their tendons are attached.

The best-known condyles are those of the distal humerus (in the elbow joint), the proximal tibia and the distal femur (both in the knee joint).

Epicondyle

Bony protrusions on the condyles, to which muscles and their tendons are attached.

Tubercle

Bumps on bones where muscles or their tendons attach, e.g. tuberculum minus and tuberculum majus of the humerus.

apophysis

Bone attachments of tendons and ligaments with their own ossification centre, which usually fuses with the main nucleus of the epiphysis. Occasionally, however, it remains independent. Tendons attached here are connected to the bone via fibrocartilage, which becomes increasingly mineralised. The cartilage provides a certain degree of elasticity. The apophyses at the muscle insertions of the rectus femoris, the adductors and the hamstring group are sometimes affected by damage. This ranges from minor changes to bony avulsion of the tendons. Depending on the affected muscles, pain often radiates towards the groin or buttocks. These disorders are easy to detect radiologically, but their appearance is quite inconsistent. Osteolytic processes and tumours must be clarified in the differential diagnosis.

diaphysis

The area of a long bone between the growth plates. This is where the bone marrow is located. Tendons attached here are connected to the bone via Sharpey’s fibres, which provide cushioning through the intertwining of the collagen fibres of the tendon with elastic fibres of the periosteum.

Epiphysis / Epiphysis ossis

The cartilaginous end of a long bone in which bone nuclei develop during growth, causing the bone to grow. The epiphysis is separated from the diaphysis, which contains the bone marrow, by the epiphyseal plate (growth plate). In relation to the centre of the body, we refer to a proximal and a distal epiphysis. If the epiphysis is part of a joint (unlike the proximal epiphysis of the distal phalanges of the toes and fingers), the epiphysis in the area of articulation with hyaline cartilage is called the articular epiphysis. a23> of the toes and fingers), it is covered with hyaline cartilage (articular cartilage) in the area of articulation.

Epiphyseal plate / growth plate

the cartilaginous transition zone of the epiphysis of a long bone a28> transition area from the epiphysis of a long bone to the metaphysis, in which bone nuclei develop during growth, causing the bone to grow. At around the age of 20, the growth in length originating from the epiphyseal plates is complete. In addition, the STH level decreases and the epiphyseal plates ossify.

metaphysis

The two (proximal and distal) areas of the shaft of a long bone in which there is no bone marrow yet.

Periosteum

Connective tissue covering the bones, completely surrounding them outside the joint surfaces covered with hyaline cartilage. In the skull, it is also referred to as the pericranium. The periosteum is one of the most pain-sensitive tissues in the body, which is why traumatic oedema under the periosteum is associated with significant pain. It aids in the nutrition and regeneration of the bone. The inner (deeper) layer of the periosteum, the stratum osteogenicum (cambium), contains bone precursor cells that can differentiate into osteoblasts, which serve to increase the thickness of the bone, but are also important for bone healing after fractures. It also contains blood vessels and nerves. The outer layer, the stratum fibrosum, is a cell-poor, collagen-rich connective tissue from which Sharpey’s fibres pass through the stratum osteogenicum to anchor the periosteum in the corticalis. These fibres, which are collagen fibres, are found in the stratum fibrosum, particularly at the tendon attachments on the diaphyses of long bones.

Cancellous bone

Spongy bone tissue found inside many bones, which is very strong but has a comparatively low mass. The space between the trabeculae (bone beams) of the cancellous bone is filled with bone marrow. The trabecular structure can change depending on the alignment and total mass of the bone under load, see bone adaptation. It is predominantly aligned according to the main load directions in the past. These most important lines of force are referred to as trajectories. For this reason, the trabecular structure varies depending on the bone, its location and the stress it is subjected to (compression, torsion or bending). The vertebral bodies, for example, are mainly subjected to compression, whereas the femoral head is also subjected to strong bending and, to a lesser extent, torsion. The structure of the trabeculae is oriented In flat bones, the cancellous bone is called the diploë, and the veins it contains are called the venae diploicae.

Corticalis

The corticalis is the layer of bone beneath the periosteum. It is very thick in the diaphysis (shaft) of long bones, as there is no cancellous bone there. Here, it is referred to as compact bone.

long bones

Usually an elongated bone with two ends (epiphyses) and a semi-cylindrical shaft (diaphysis) containing bone marrow. The epiphyses at both ends of the long bone are connected to the diaphysis by the growth zone (epiphyseal plate). Once growth is complete, the epiphyseal plates are then closed. Apophyses serve to form the insertions of ligaments and tendons.

Trabeculum

Trabeculae (bone beams) are a macroscopically visible, structured, sponge-like network of bone tissue in the cancellous bone, which is mainly aligned in the direction in which the bone is subjected to the greatest stress, following the trajectories (virtual lines of maximum force flow). Compared to a solid cortical bone, this saves mass and weight, but also allows adaptation to changing loads. The trabecular structure becomes denser in areas subject to higher loads. The trabecular structure therefore differs in bones that are mainly exposed to compressive loads, such as the tibia, and those that are subject to bending or torsion, such as the transition from the femoral shaft to the head. Micro-injuries are broken down by osteoclasts and rebuilt by osteoblasts. In long bones, the cancellous bone is absent at the level of the medullary cavity; instead, the cortical bone is thicker there. The remodelling processes of the two bone components differ. Since the cancellous bone has a turnover that is approximately 10 times faster, pathological processes such as

osteoporosis become visible there first and foremost. Where the trabecular structure has to absorb high bending loads, fractures are more likely to occur. The fact that the trabeculae have no vessels but are supplied by diffusion from the vessels of the bone marrow limits the thickness of the trabeculae to around 300 µm.

bone marrow

Connective and stem cell tissue located in the centre of larger bones that forms blood cells. It is found in the large marrow cavity inside the diaphysis of long bones, but also in the spaces between the trabecular structure. A distinction is made between red bone marrow (medulla ossium rubra), which forms blood cells, and yellow bone marrow (medulla ossium flava), which stores fat but no longer contains pluripotent stem cells to form blood cells. In adults, red bone marrow weighs around 400 g, of which approximately 180 g forms erythrocytes and leukocytes, with the remaining 40 g forming thrombocytes. In infants, red bone marrow is found in all bones, but with increasing age, it is replaced by yellow bone marrow in the shafts of the long long bones. Only where red marrow is still present can it possibly expand. Red bone marrow also contains a certain amount of fat, approximately 35% in the vertebral bodies and approximately 75% in the rib bones. In addition to red and yellow marrow, there is also gelatinous white marrow, in which fat is replaced by water. This cannot be converted back into red marrow either. White marrow occurs mainly in old age and in seriously ill patients. The starting point for blood cell formation is the haemocytoblast, which divides into another haemocytoblast and a precursor cell of erythrocytes, leukocytes or thrombocytes.

Medullary cavity/medullary chamber

The medullary cavity is the large interior space of bones containing bone marrow, which is lined with endosteum and located inside the cortical bone. The medullary cavity is supplied by arteries that pass through small holes (nutricia foramina) in the bone substance. In young people, the medullary cavity still contains red bone marrow, while in adults it contains only yellow bone marrow.

osteoclasts

Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells that serve to break down bone. They develop from monocyte stem cell lines. Their activity forms Howship lacunae on the surfaces of the trabeculae, which are centres of bone resorption and starting points for reconstruction.

osteoblasts

Cells that develop from less differentiated precursor cells and form the unmineralised ground substance of bone. They produce alkaline phosphatase, which controls bone mineralisation. Osteoblasts give rise to osteocytes.

osteocytes

Mature bone cells that develop from osteoblasts when they become enclosed in the bone matrix they have formed. Osteocytes communicate with each other via their processes and serve to maintain both the bone matrix and calcium homeostasis. They are also mechanosensitive and can stimulate osteoblasts and inhibit osteoclasts when bone mass needs to be increased to improve stability.

Callus

In secondary (indirect) fracture healing, where the fracture fragments do not fit together exactly and interlock, the osteoblasts form a bridge, which is visible radiologically as a thickening of the bone fragment around the fracture. The callus is the scar tissue of the bone. Around the 7th week, ossification begins through increasing calcium deposition, and after about 25 weeks, the bone is healed. In the case of direct (primary) fracture healing with up to 1 mm distance between the bone fragments, no callus formation takes place, as the bone heals through the Haversian canals, the central basic unit of an osteon in the compacta. For bone healing, see Fracture.

fracture healing

There are two mechanisms of fracture healing:

direct (primary fracture healing)

If the periosteum has remained intact or if the fracture ends are still connected, primary fracture healing takes place. If the fracture ends are less than 1 mm apart, capillary-rich connective tissue grows into the fracture gap and no visible callus forms around the fracture site. Precursor cells of the osteoblasts (osteoprogenitor cells) from the periosteum and endosteum accumulate around the existing capillaries and initially form osteons arranged parallel to the fracture surface. These are later restructured parallel to the longitudinal axis of the bone by erosion tunnels. After three weeks, a functional bone is restored.

indirect (secondary fracture healing)

Waren die obigen Bedingungen nicht erfüllt, war also etwa der Spalt größer als 1 mm, muß der Knochen, beginnend mit Kallusbildung (intern und extern) in einer fünfstufigen Procedere repariert werden:

- Verletzungsphase mit Entstehung eines Hämatoms im Gelenkspalt

- Entzündungsphase mit Einwanderung von Makrophagen, Granulozyten und Mastzellen; Freisetzung von Histamin und Heparin. Mesenchymale pluripotente Stammzellen differenzieren zu Osteoblasten, Fibroblasten und Chondroblasten. Zytokine und Wachstumsfaktoren wirken steuernd für Zelldifferenzierung und Angioneogenese.

- Granulationsphase (4.-6. Woche): das mittlerweile mit Fibrin und Kollagen gebildete Netz in dem Hämatom wird durch Granulationsgewebe mit Fibroblasten, weiterem Kollagen und Kapillarisierung ersetzt. Nicht durchblutetes Knochenmaterial wird von Osteoklasten abgebaut, neues Knochenmaterial wird von Osteoblasten vom Periost aus aufgebaut.

- Kallushärtung (Dauer: 3-4 Wochen): der entstandene Kallus wird mineralisiert, was zu einem bzgl. des Kollagens noch ungerichteten Geflechtknochen führt. Die Kapillaren und die Grobstruktur des Knochens entsprechen schon der physiologischen Flußrichtung und Hauptbelastungsrichtung

- Remodelling phase: Modelling and remodelling: the cancellous bone is broken down into physiological lamellar bone with Haversian canals and Volkmann’s canals. The medullary cavity is restored. Complete healing should be achieved after 6–24 months.

If fracture healing is disrupted, pseudoarthrosis may develop, i.e. an insufficiently hardened and remodelled fracture site with reduced stability (non-union). If fracture healing lags behind the time frame (delayed fracture healing), it must be checked whether the immobilisation was sufficient or needs to be improved. If the fracture fragments have not been correctly repositioned, the fracture will heal in a malposition (malunion), whereby the longitudinal axes of the two (main) bone fragments may be unequal or one bone fragment may be twisted around the longitudinal axis relative to the other. If a malunion occurs at one end of the bone through the articulating surface, incongruity may result. In addition, fracture healing may remain fibrous for a long time. The fibrous tissue is usually replaced by bone tissue after a period of time.

Osteolysis

Osteolysis is the active breakdown of bone tissue, whether physiological as part of the constant renewal of bone or due to a lack of maintenance stimuli (over 800 µS), or pathological as part of a disease. These include:

- Metabolic bone disorders such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, osteomalacia and hyperparathyroidism

- Bone cysts and primary bone tumours (such as osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma), bone metastases or haematological neoplasms such as plasmacytoma

- Inflammation (infectious or aseptic) such as arthritis, osteomyelitis, RA, periodontitis of the jawbone

- Implant loosening (due to abrasion of endoprostheses or osteosynthesis material), also in the jawbone in cases of peri-implantitis and tooth loss

- Amyloidosis

traction apophysitis

Traction apophysitis is a stress lesion in the area between an apophysis and its bone in young people. It mainly affects young athletes and is regularly an overuse syndrome. It is classified as aseptic bone necrosis.

During periods of rapid growth, the apophysis is less stable due to increased somatotropin production. The relative shortening of the muscles, which adapt only slowly during growth, also leads to increased tension on the apophyses. The onset of hormone production during puberty leads to a comparatively rapid increase in muscle strength, which also puts more strain on the apophyses than before puberty. These three factors make them susceptible to overuse as well as trauma. Therefore, athletic children in growth spurts are particularly at risk. Girls are most commonly affected by Osgood-Schlatter disease between the ages of 10 and 11, while boys are affected between the ages of 13 and 14 due to the later onset of puberty. In the case of Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease, both sexes are on average 2 years younger. Sever’s disease (apophysitis of the calcaneus at the Achilles tendon insertion) peaks between the ages of 8 and 12.

The most well-known types of apophysitis are Osgood-Schlatter disease and Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease. Iselin’s disease (traction apophysitis of the fifth metatarsal bone) and Little League elbow (medial epicondyle apophysitis) at the medial epicondyle of the humerus are also included, but Little League shoulder is not, as it is not apophysitis but epiphysiolysis a7>.

In addition to traction apophysitis, apophyseal tears, i.e. avulsions, can also occur in some apophyses when certain triggers are present, for example:

- SIAS: Sprint, Absprung, Tritt ins Leere

- SIAI: explosive hip flexion as when kicking with the instep, or when the foot is blocked externally (ground, opponent) during the kick, in this case, excessive callus formation can lead to impingement

- Tuber ischiadicum: jerky, wide hip flexion with the knee joint more or less extended (DD: strain of the hamstring group, PHT)

- Iliac crest (rare): jerky flexion/rotation of the upper body

- Trochanter minor: jerky eccentric movement of the iliopsoas

Epiphysiolysis

Epiphysiolysis is traumatic or spontaneous damage to the epiphyseal plate with partial or complete separation of the epiphysis from the bone. This often results in translation of the two bone segments. Epiphysiolysis is classified according to Aitken (grades 0–4) or Salter-Harris (grades 1–4). Both classifications correspond to ascending cardinal numbers. Epiphysiolysis can only occur before the end of the growth phase. If the epiphyseal plate is already partially closed (ossified), it is already a fracture. The best-known epiphysiolysis is probably epiphysiolysis capitis femoris, which is an orthopaedic emergency and requires immediate surgery. Epiphysiolysis of the shoulder (proximal humerus) is often caused by birth trauma or, alternatively, by athletic overuse. Young gymnasts are prone to distal radial epiphysiolysis (gymnast’s wrist, distal radial physeal stress syndrome).

aseptic bone necrosis

Aseptic bone necrosis refers to osteonecrosis that is not caused by infection. The pathomechanism is not yet fully understood, but unclear factors lead to the occlusion of a supplying vessel (ischaemia). The presumed causes can be grouped as follows:

- genetic/constitutional factors

- Trauma or repeated microtrauma

- vascular factors

- Ernährung, Medikamente, andere iatrogene Faktoren

Es sind viele einzelne Risikofaktoren bekannt:

- endokrine Gründe

- iatrogen: Chemotherapie, Thermotherapie, Bisphosphonate, Immunsuppression, Kortison

- Mangelernährung

- chronischer Alkoholabusus

- Mangelernährung

- SLE

- RA

- sickle cell anaemia

- prolonged exposure to environments with artificially increased air pressure, such as in mining

Osteonecrosis can occur in various locations in both the upper and lower extremities, most of which now have their own names. The best known are probably:

- Osgood-Schlatter disease

- Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome

- Scheuermann’s disease (no longer classified as osteonecrosis)

- Perthes disease

- Ahlbäck’s disease

- Blount’s disease

- Osteochondrosis dissecans (a special case because it occurs subchondrally, i.e. at the transition from bone to cartilage)

Osteonecrosis is classified into four stages:

- Initial stage: no changes are visible on X-ray, only on MRI, e.g. a bone bruise or bone marrow oedema.

- Osteopenia, which is visible on X-rays as increased radiolucency. Osteolysis can be seen on MRI, possibly with surrounding bone marrow oedema or microfractures.

- X-rays reveal sclerosis of the area surrounding the osteonecrosis, while MRI scans show the sclerotic rim.

- Occurrence of secondary defects such as malalignments or joint surface defects, osteoarthritis

Exostosis

An exostosis is a bony growth on the compacta, e.g. as a benign bone tumour or osteoma. It can be irritation-related, i.e. caused by repeated local pressure, in which case it is also referred to as a bony ganglion (ganglion).

Osteophyte

Bone mass proliferation, usually in the context of arthrosis from grade 2 onwards. The arthritic cartilage changes lead to incongruities in the joint surfaces and local increases in pressure, which in turn lead to subchondral sclerosis and, above that, to local cartilage and bone necrosis (debris cysts). This material accumulates at the edge of the joint surfaces and calcifies into osteophytes, which literally means bone spurs. They are detectable in ultrasound and X-ray and are considered a sign of advanced osteoarthritis. They can cause consequential damage by exerting local pressure on nerves or other soft tissues (tendons, ligaments). If they break off, they can also lead to further problems as loose bodies in the joint, e.g. impingement.