Linkmap

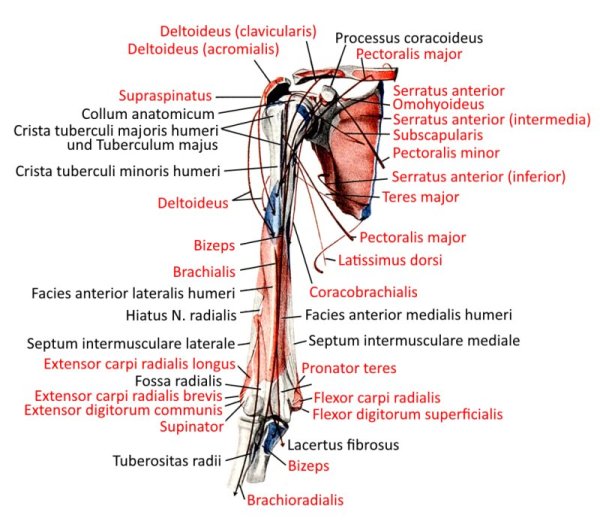

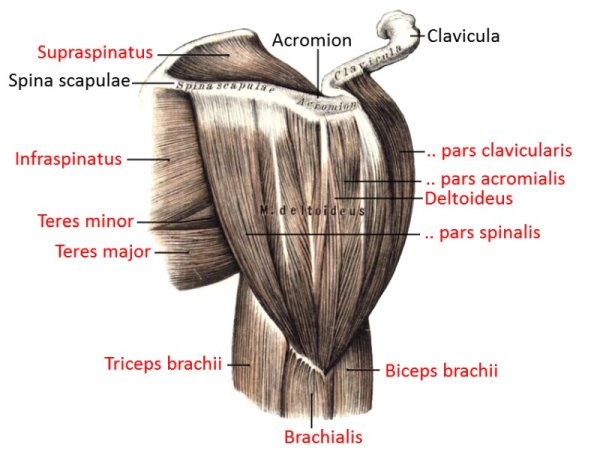

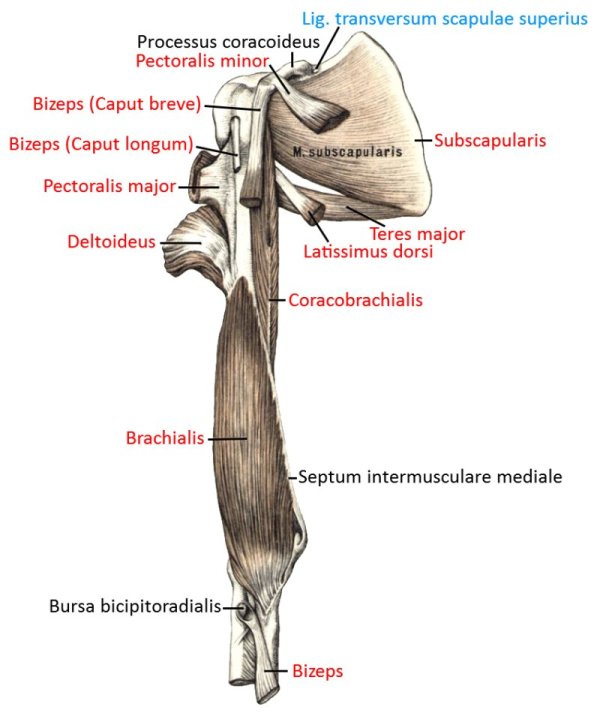

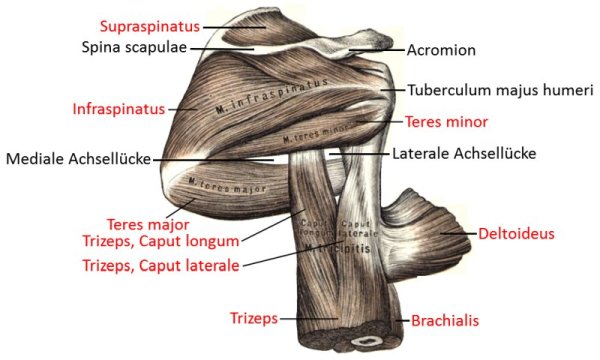

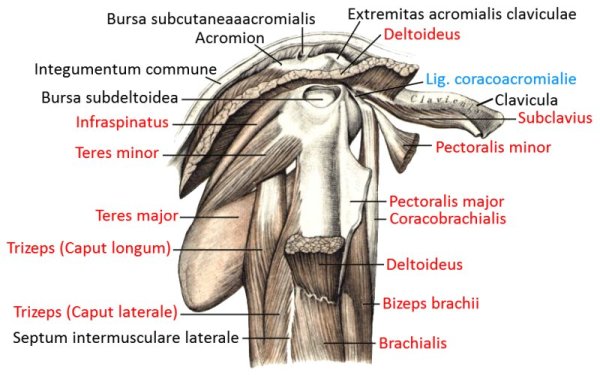

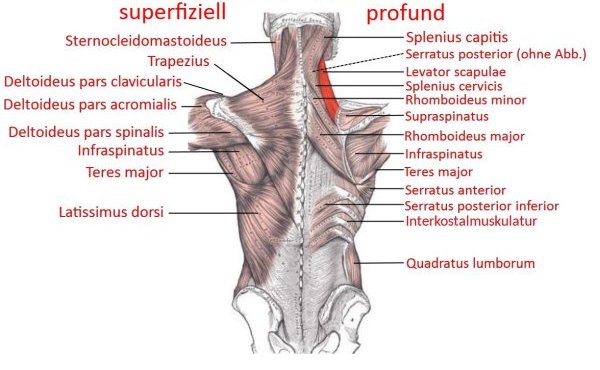

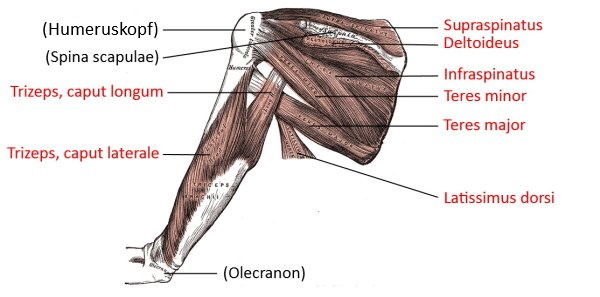

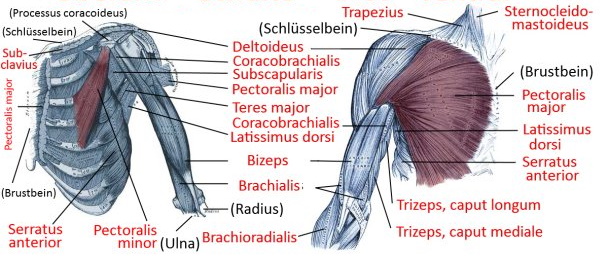

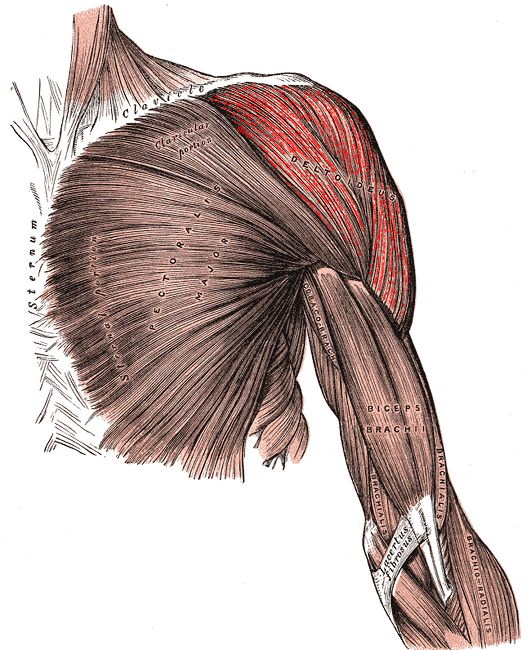

Deltoid

originates from the lateral third of the clavicle and also causes anteversion. Below 60°, it contributes to lateral adduction. From 60°, the pars acromialis becomes actively insufficient and the pars clavicularis acts as main agonist of the lateral abduction together with the pars spinalis . Furthermore, the pars clavicularis can support the internal rotation of the arm.

pars clavicularis

arises from the acromion and supports the pars clavicularis in the anteversion as well as the pars spinalis during retroversion. Pars acromialis cannot yet generate a moment when the arm is adducted because its course is mediocaudal to the glenohumeral joint. From an initial 10-15° supraspinatus performed by the lateral abduction, the pars acromialis performs the essential work, before it starts to become actively insufficient at around 60° and the partes clavicularis et spinalis take over the further lateral abduction.

pars acromialis

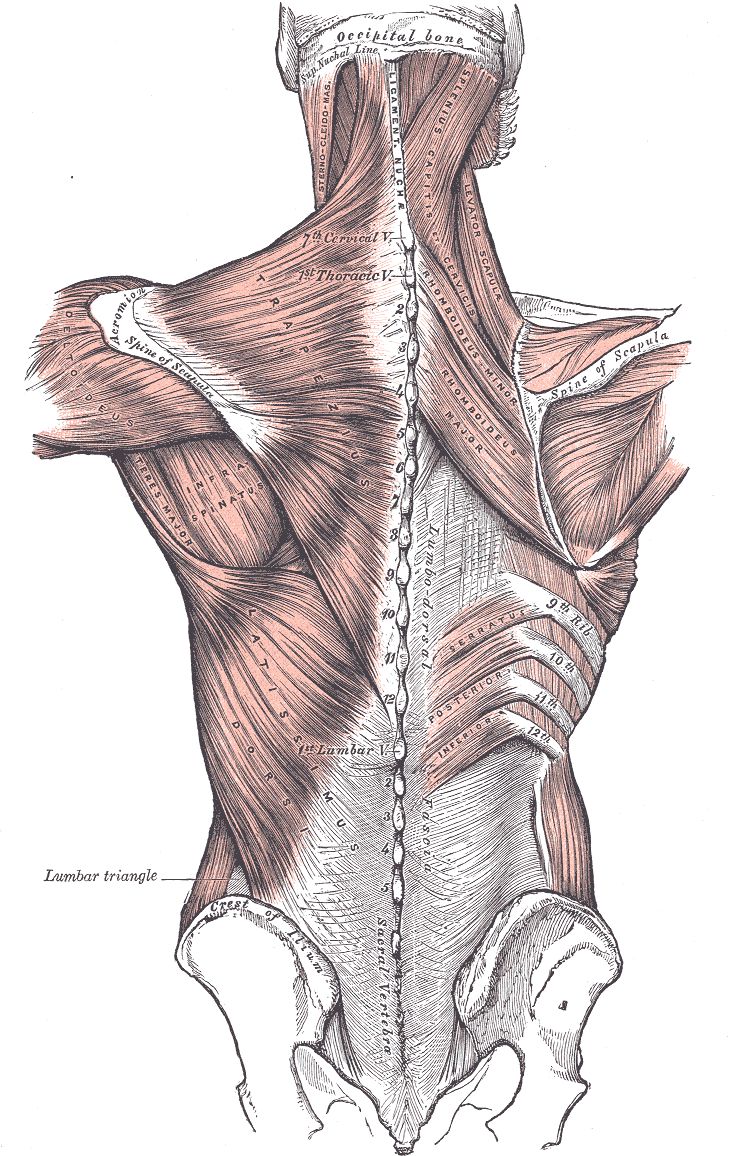

originates from the spina scapulae and, in addition to the lateral adduction (up to 60° lateral abduction) the retroversion. From 60° lateral abduction, it acts together with the pars clavicularis as the main agonist in lateral adduction. The pars spinalis can also support external rotation.

pars spinalis

originates in the spina scapulae and causes retroversion in addition to lateral adduction (together with the pars acromialis). From 60° it also contributes to adduction. It can also support exorotation

The deltoid pushes the head of the humerus into the acetabulum and thus provides muscular support for the joint

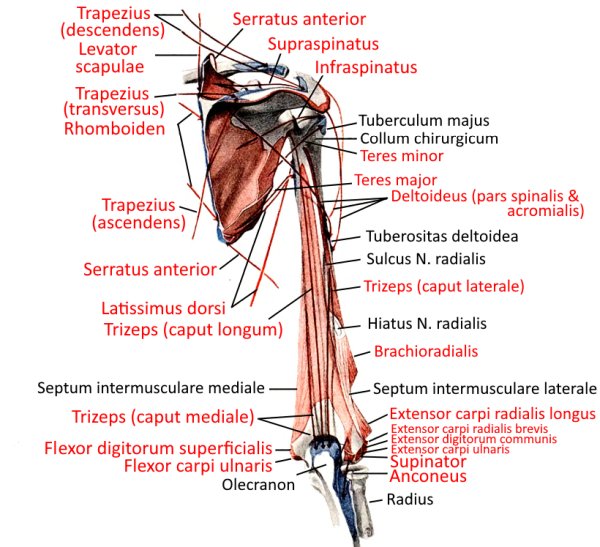

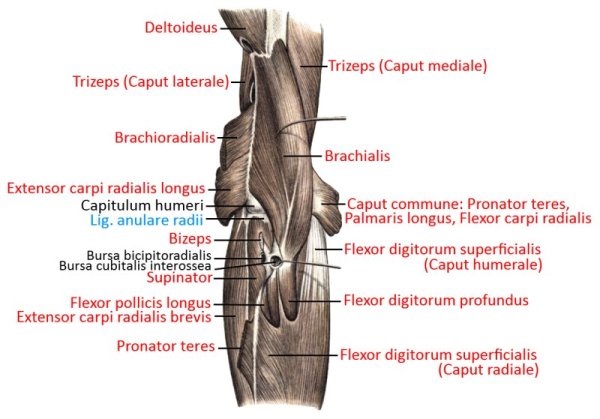

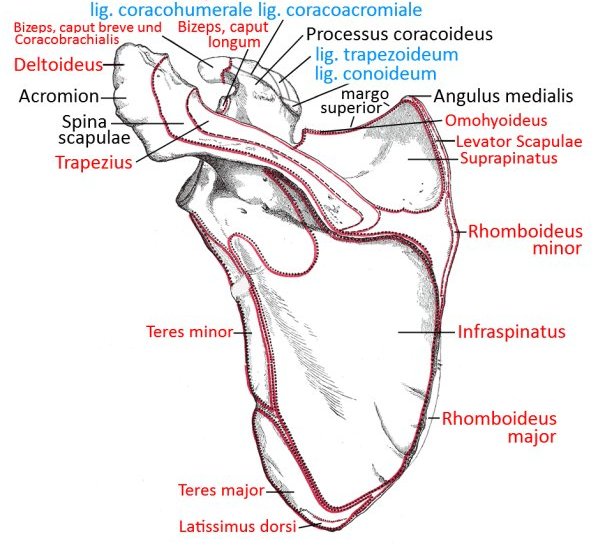

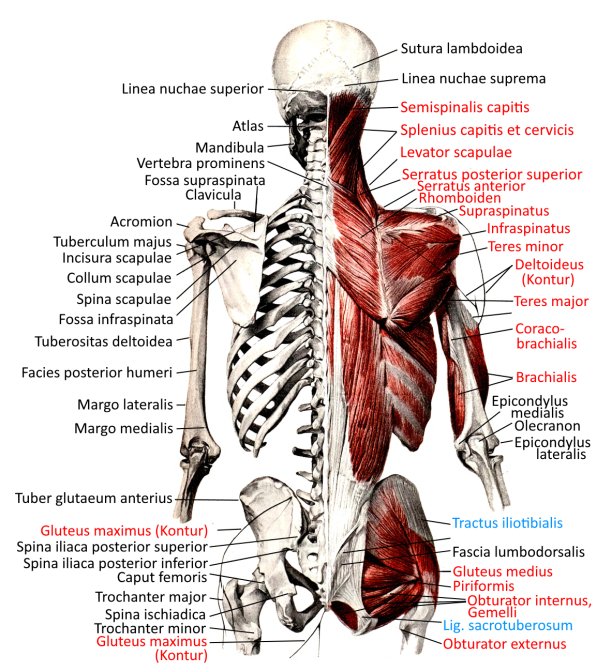

Origin:

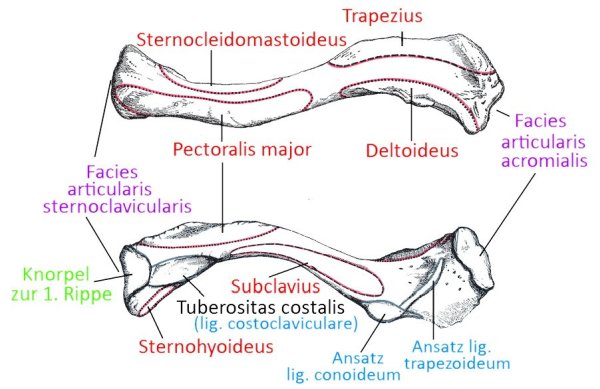

- Pars clavicularis: Clavicle

- Pars acromialis: acromion of the shoulder blade

- Pars spinalis: shoulder blade(spina scapulae)

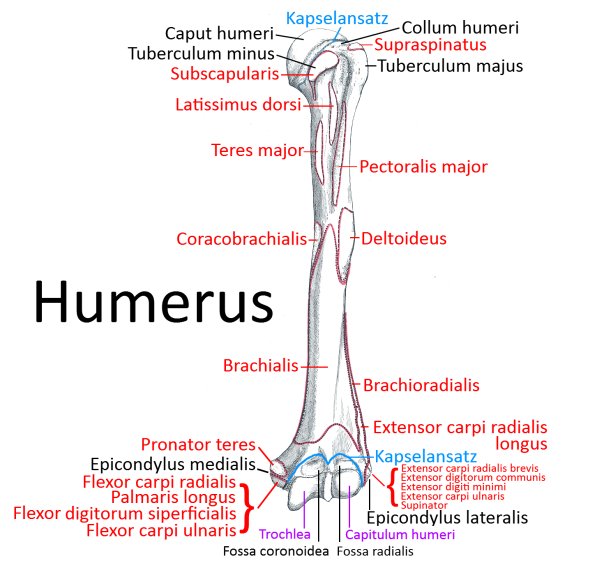

Attachment: deltoid tuberosity of the humerus

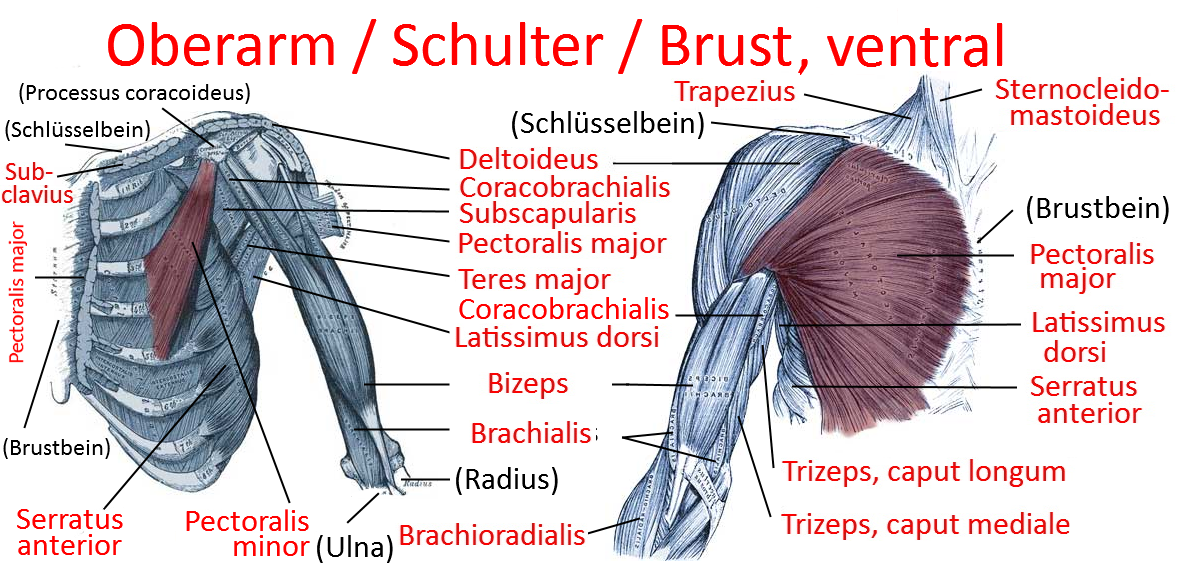

Innervation: Nervus axillaris from fasciculus posterior of plexus brachialis (C5-C6), akzessory rami ventrales of nervi thoracici

Antagonists:

Movement: Fixation of the humeral head; abduction by pars acromialis between 10° (depending on the literature: 15°) and 60° (before this the supraspinatus must lift, after this active insufficiency), from 60° lateral abduction pars clavicularis and pars spinalis continue to abduct up to approx. 90°, from which angle the scapula must rotate outwards for further lateral abduction; pars spinalis: retroversion and exorotation, below 60° it supports lateral adduction . Pars clavicularis: endorotation below 60°, it supports lateral adduction. Its rotational functions are limited to small angles of lateral abduction. The acromial part can support retroversion with dorsal fibers and anteversion with frontal fibers.

Strengthening postures (): Strengthening must also be differentiated according to proportion:

- pars clavicularis: upface dog, headstand, three-point headstand, dog elbow stand, elbow stand, right-angled elbow stand, handstanddips, downface dog: Dips, dog head down: Transition to pole and back, dog head down: Transition to dog elbow stand and back

- pars acromialis: 2nd warrior pose, ardha vasisthasana and vasisthasana, when the supporting arm is pressed bent away from the feet.

- pars spinalis: jathara parivartanasana, upface dog: with feet upside down

Stretching postures (): With the deltoid, as with the trapezius, a distinction must be made between the different parts:

- pars clavicularis: namaste: on the back, gomukhasana, purvottanasana, setu bandha sarvangasana, sarvangasana, uttanasana: arms behind the body, prasarita padottanasana: arms behind the back, maricyasana 1, maricyasana 3

- pars acromialis: The pars acromialis is usually relatively mobile because the arm, which often hangs down, maintains mobility. At best, stretching is possible in lateral adduction of the arm in front of or behind the body without significant frontal abduction, e.g. in gomukhasana

- pars spinalis: as the pars spinalis retroverts and abductslaterally, a moderate frontal abduction without wide lateral abduction as in garudasana is required for stretching

more charts