yogabook / asanas / garudasana

Contents

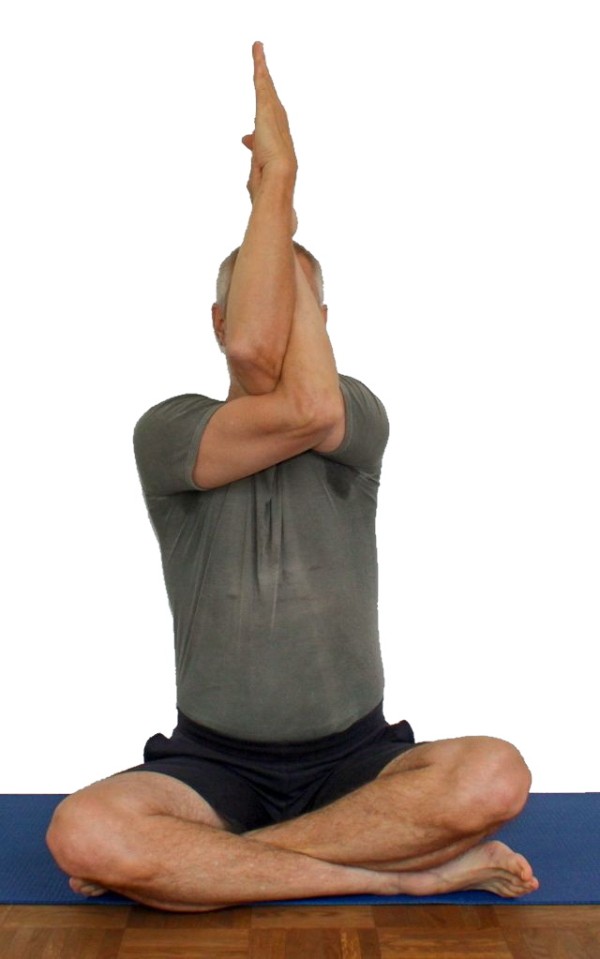

garudasana

„eagle“

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

instructions and details with working links as PDF for download/print

Feedback: We’d love to hear what you think about this description, give us feedback at:

postmeister@yogabook.org

Last modified: 30.12.2018

Name: garudasana

trivial name: eagle

Level: FA

- classification

- contraindications

- effects

- preparation

- follow-up

- derived asanas

- similar asanas

- diagnostics

- instructions

- details

- variants

Classification

classic: standing pose

Contraindication

Effects

- (221) Shoulder blade: stretching of the retractors for protraction

- (256) Shoulder joint: stretching for lateral/transverse adduction

Preparation

Balance on one foot can be prepared with:

- warrior 3 pose

- vrksasana

- hasta padangusthasana

- eka pada prasarita (one leg raised)-variant of uttanasana

- ardha chandrasana

- parivrtta ardha chandrasana

- parsvottanasana

Lateralisation and also protraction of the shoulder blade (outward movement):

Follow up

If the calves are strained from the balancing work, the following stretches will help:

- downface dog

- warrior 1 pose

- parsvottanasana

- parivrtta trikonasana

- squat 2

- uttanasana with ball of foot on a block

Derived asanas:

Similar asanas:

Diagnostics (No.)

(852) Calves:

The calf muscles are clearly strained in this pose. The stance becomes more stable when the weight is moved further towards the ball of the foot. However, the further the load is shifted away from the heel in this direction, the greater the strength endurance demand on the calf muscles (especially the triceps surae). However, the calf is less prone to cramps here. However, if calf cramps occur quickly, this often indicates a lack of strength endurance or a supply problem such as a lack of calcium (cramps even at rest) or magnesium (load-dependent) in the blood or a lack of blood circulation. This generally has nothing to do with nocturnal calf cramps, which are usually caused by prolonged stretching movements (plantar flexion) in the ankle due to the current dream events. However, if cramps occur at rest, this may indicate a calcium deficiency.

(221) Shoulder: stretching of the retractors for protraction

This is one of the best ways to assess and promote protraction of the shoulder blades (the movement to the side and forwards). The angle of frontal abduction is nothing special at around 90°, so it requires no special preparation and provides less information than larger angles. However, it is possible to recognise, for example

- various pathological changes in the shoulder joint such as impingement syndrome, frozen shoulder, subluxation tendency, calcifications of the biceps tendon, which cannot all be discussed here and require clarification.

- side discrepancies in flexibility.

The really exciting thing about garudasana is the outward/forward movement of the shoulder blades which goes beyond pure lateralisation in far protraction in combination with their downward movement (depression). This can stretch the levator scapulae very well, which is often responsible for chronic scapular elevation and tension from the inner upper shoulder blade to the upper cervical spine or is at least partly responsible alongside the trapezius. Apart from garudasana, there are hardly any exercises that can help this particular tension or shortening; it goes far beyond poses that lateralise the shoulder blades such as caturkonasana. The inability to place the hands on top of each other (partially overlapping) in this pose, which is not uncommon, is diagnostic of a lack of protraction, usually due to shortening of the levator scapulae and possibly the rhomboids, and sometimes also a lack of the capability to turn out of the arms in the glenohumeral joint.

(271) Shoulder:

In this pose the upper arms are widely turned out in the shoulder joint. According to the construction of the pose, this results from the endeavour to bring the wrists (offset in the median plane) into alignment with each other. It is not uncommon for the capability to turn out the arms in the glenohumeral joint to be so limited that this is not yet possible and a supporter is needed to enable the performer to push with the fingers of the lower hand into the upper hand so that he can work to gain further capability to turn out the arms. This phenomenon may be partly due to a lack of external rotation capability in the glenohumeral joint and partly due to a lack of protraction capability of the shoulder blades.

(950) Foot deformities:

Foot deformities can make standing on one foot and balance difficult. In this case, the standing foot can be assessed from all sides.

(960) Foot:

In this pose, misalignments (subluxations) of foot bones, usually tarsal bones or the metatarsal bones, can become noticeable directly or in the neighbouring joints. In addition, in the case of hallux valgus, the metatarsophalangeal joint area will show increased pressure pain. Metatarsalgia is pain on pressure or pain on movement in the area of the ball of the foot and can have various causes.

(913) Sole of the foot:

If cramping of the muscles of the sole of the foot or calf occurs in this pose, the causes should also be looked for there, which may include hypertonus, malalignment, foot deformity, damage caused by wearing inadequate footwear for a long time or overuse.

This pose is one of the few – bsides e.g. trikonasana – to show adduction in a hip joint, which may indicate hip damage:

- Arthrotic change of the joint

- Arthritis (joint inflammation) of various kinds

- Current dislocation / subluxation, which would cause a significantly increased sensation of tension in various muscles spanning the hip joint

- (sub)luxation tendency due to labrum damage or ligament laxity (joint instability)

- Joint trauma suffered, which may cause pain in the joint even after many weeks or months

Variants:

(S) upper half, press down shoulder blades

(S) turn hands and depress shoulder blades

(P) palpate the levator scapulae

Instruction

- This pose consists of two synchronised movements, one of the arms and one of the legs. The arms are described first and then the legs. If necessary, practise them separately before joining them together.

- Stand in tadasana.

- The movement of the arms: hold the arms so that the upper arms stretch horizontally and parallel to the front away from the trunk, the forearms stretch parallel and vertically upwards and the palms face each other with the wrists stretched out.

- Bring the left elbow over the right upper arm (maybe with a swing) and the left hand (which is now further to the right) behind (further away from the body) the right hand to the left and then place the left palm on the right palm as far as possible.

- Keep moving the arms upwards without tilting the forearms towards the face, without turning the hands in any direction other than 90° to the line of vision and without moving the shoulder blades upwards, on the contrary: move them towards the pelvis (in depression).

- Moving the legs: stand on the right leg, lift the left leg slightly and bend it slightly (approx. 20-40°); bend the right leg too.

- Wrap the left leg around the right leg by moving the left thigh in front of the right and placing the left lower leg on top of the right from behind so that the left foot hooks around the right lower leg from back-right to front-left.

- Keep the pelvis upright and the upper body stretched upwards and move the arms further upwards as the pose progresses.

Details

- Make sure that the hands do not rotate and that the palms are always facing inwards, i.e. the palms are parallel to the median plane.

- Hold the wrists together (more precisely: offset forwards or backwards in a vertical plane); to do this, press the fingers of the lower hand firmly into the upper hand.

- Make sure that the forearms do not tilt towards the face, which happens easily when they are pushed further up.

- Do not pull the shoulder blades upwards, but keep them down. Don’t confuse the movement of the elbows with a movement of the shoulder blades. The angle of the upper arms should not be less than horizontal in the sense that the elbows should be higher than the shoulders.

- It is not uncommon to see that the fingers of the lower hand do not reach the upper hand, but that the forearms are still at an appreciable angle to each other and too strongly inclined to the vertical in the frontal plane. As described above, this phenomenon may be partly due to a lack of external rotation in the glenohumeral joint and partly to a lack of protraction of the shoulder blades. It is then necessary for a supporter to push the wrists medially so that the performer can push with the fingers of the lower hand into the upper hand and in this way work on the capability to turn out the arms in the glenohumeral joint and on the capability to protraction the shoulder blades. In some cases, this is due to a particularly muscular configuration of the arms, which, especially with high muscle tone and thus low flexibility of the muscles against external pressure, increases the distance between the two humerus bones to such an extent that the fingers of the lower hand inevitably appear „too short“. In this case, only props can be used, i.e. a belt that limits the distance between the wrists and thus ensures effectiveness. Because the forearms in these cases are often still tilted significantly against the vertical, it may be necessary to use friction mediators such as a patch between the forearm and the belt to prevent the belt from slipping downwards and thus reducing its effectiveness. If there is sufficient strength to prevent the wrist from bending and moving into dorsiflexion, the belt can also be placed around the palms between the thumb and index finger. But it is better to grip the belt tightly with your hands in wide dorsiflexion and both wrist joints then bend in the direction of palmar flexion, which brings the wrist joints closer together and improves the exorotation of the arms and thus the effectiveness of the posture.

- It is not the primary purpose of the pose to strengthen the thighs by bending the knee joint as far as possible, but this can be included to a certain extent as long as it does not impair stability.

- The strength of the forearms can be a limiting factor that impairs the effect in the direction of turning out the upper arms and protracting the shoulder blades, namely if the finger flexors, which press the fingers of the lower hand into the upper hand, and the palmar flexors of the wrist, which stabilise it against bending away dorsally, cannot perform their work for long enough and intensively enough to ensure that the desired effects in the shoulder joint and shoulder blade area happen sufficiently. The strength of the pronators of the upper arm and the supinators of the lower arm also plays a role in achieving the full effect.

- If the performer finds it difficult or hard to keep the shoulder blades permanently depressed against the pull of the levator scapulae, poses such as upface dog or tolasana can be used to strengthen the depressors causally and permanently on the one hand and to improve awareness of this movement on the other.

- It is advisable to bring the upper arms into position with a swing, at least if the pectoralis major has a high tone and therefore tends to cramp due to its very short sarcomere length. Less flexible retractors of the shoulder blades, which can also significantly increase the required contraction force of the pectoralis major and thus the tendency to cramp, would prove to be an aggravating factor. Previous muscle training can also significantly increase the tendency to cramp. In all these cases, it is advisable to bring the upper arms into position with sufficient momentum instead of having to exert force towards the end of the movement and risking a cramp in the pectoralis major.

- The hands will necessarily only partially cover each other. The more voluminous the arm muscles and the higher their tone, the lower the overlap, so that the fingers of the lower hand can often only be pressed into the palm or onto the thenar.

Variants

upper half

Concentration on the arm position

Instructions

- Sit comfortably, e.g. cross-legged, and only perform the arm-related part of the exercise

Details

- Here you can concentrate on the beneficial effects of the arm posture of garudasana, as omitting the leg posture frees up a lot of attention.

- With this exercise it is possible to stretch the small muscle on the upper inner edge of the shoulder blade (levator scapulae) in a very focussed way. Although this muscle does not tend to become noticeably tense very often, when it does it is very uncomfortable and difficult to relieve – ideally with this pose.

(S) upper half, press shoulder blades down

Instructions

- Take the pose as described above.

- While sitting or standing, the supporter presses both shoulder blades towards the pelvis with sufficient force and corrects any evasive movements that may occur ventrally.

Details

- The corrections to be made also include bringing the forearms back into a vertical position if they are tilted towards the face and, if necessary, realigning the hands perpendicular to the line of vision (horizontal rotation) and raising the arms further if necessary.

(S) with belt

Instructions

- Take the stance as described above.

- The supporter attaches the belt to the performer. Basically, the belt can be placed around the wrist or held in the hands. The best way to do this is to place the belt in the hands and hold them in almost maximum dorsiflexion so that the performer can increase the intensity on both sides by reducing dorsiflexion.

Details

- Fixing the belt statically usually does not do justice to the posture. The sensation of stretching usually decreases over the duration of the exercise, so that the belt would have to be reattached to be effective. It is therefore advisable to hand over the task and the possibility of regulation to the performer. This is best done using the technique described above.

(S) Turn hands and depress shoulder blades

Instructions

- Take the stance as described above.

- The supporter grabs both of the performer’s hands with one hand and turns them so that the palms are perpendicular to the performer’s line of vision. At the same time, he presses the shoulder blades to the ground with the other hand.

Details

- Aligning the hands perpendicular to the line of vision again (rotation in the horizontal plane around a vertical axis) helps to improve protraction of the shoulder blades and thus better stretching of the levator scapulae. The other correction, pushing down the shoulder blades, is even more important according to the main direction of the levator scapulae. The sum of both corrections should produce a good stretching effect.

(S) Lift arms

Instructions

- Hold the position as described above.

- The supporter raises both elbows and makes sure that the forearms remain vertical.

Details

- To lift both elbows, it is enough to push the lower one upwards. During this movement, it is all too easy for the forearms to leave their vertical position and tilt towards the face. This always happens if the performer does not actively stretch the elbow joint a little with the amount of lifting.

(S) Palpate levator scapulae

Instructions

- Take the posture as described above.

- While sitting or standing, the supporter presses both shoulder blades with sufficient force in the direction of the pelvis and palpates the levator scapulae on both sides with light pressure.

Details

- As a rule, the tension and pressure sensitivity is slightly higher on the side of the upper arm. Deviations from this rule, for example in such a way that the same side is always felt more with both possible crossings of the arms, usually mean increased tension on this side, as is often found in the dominant arm.

- If there is a clear sensitivity to pressure even with slight pressure, the resting tone of the levator scapulae is so high that it is usually felt as unpleasant tension, even if the arms hang passively next to the body. There are usually indications of the cause in the movement history.

- If necessary, pressure massage can also be performed during palpation.